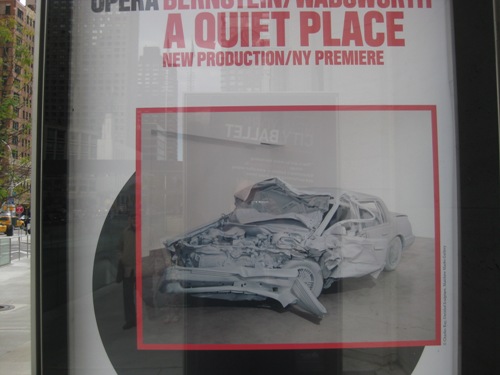

Top: Poster for "A Quiet Place."

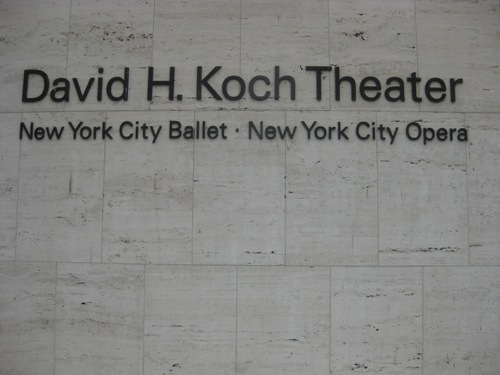

Bottom: Facade of the David H. Koch Theater

Photos by Allan M. Jalon

I heard his deeply growling voice before I saw him, as I crossed the wide plaza of Lincoln Center. His mouth was an open dark circle, like a singer. He boomed jagged phrases, a kind of speech to the crowd milling before the poster for Leonard Bernstein's opera, "A Quiet Place," which started in under an hour. A black opera cape fluttered about his shoulders like wings. He gestured vividly, face flashing with what seemed like fury, twisting, nodding, as his powerful hands opened and closed.

Some people stopped, clearly stunned at his intensity, and by something else I couldn't fathom. Others waved him off, as if he were crazy, and strode into the theater. In a lull, he noticed me, took a mad drag from a cigarette, sucked the smoke into his chest and asked: "Show some chutzpah and heed my call! Give me some hope!" He gestured toward the theater facade behind him. "Don't go waltzing in there with the rest of New York!"

"Not go?" I asked. "As in not go to the opera?"

"An Einstein!" he declared, an ironic smile spreading wide, though the eyes glistened with grief. "That's right! Stand up! Fight! Hineni! You know what that means, in Hebrew?" He jumped in before I could answer: "The Lord called to Abraham, to Moses! And they answered: Hineni! Here I am! I answer with my whole being! And they moved mountains, even when the mountains seemed unmovable--and so can we! DO NOT GO into that theater, folks! Wipe that name OFF that theater!"

He put on a pair of reading glasses and pulled out an article. I recognized the New Yorker's delicate type. His modulated baritone chanted what sounded like Schoenbergian Sprechstimme, a Yom Kippur chant or even a lost fragment from West Side Story: "The great Jane Mayer digs these details! She's on fire, and it burns me and should burn everyone! The Kochs are longtime libertarians who believe in drastically lower personal and corporate taxes, minimal social services for the needy..."

Yanking off the reading glasses, he went on, his voice a rumble of mournful dismay: Minimal services for the needy and much less oversight of industry--especially environmental regulation.

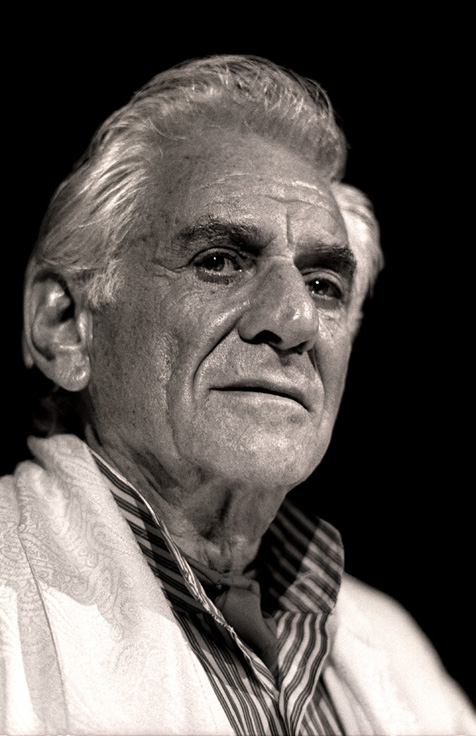

I knew who this was. I'd never heard Leonard Bernstein give one of his speeches. But I'd read a few, like the one at a New York cathedral on New Years Eve, 1984. He turned his fury on the priorities of the Reagan era, denounced a hypocritical superstructure of multi-national giants, a time when war and commercial wealth eclipsed responsibilities to feed, house, clothe and build.

And here he was, a Jeremiah from the grave, back at his dear Lincoln Center, where he'd conducted Aaron Copland's Fanfare for the Common Man at the ground-breaking. It is 20 years since Leonard Bernstein died -- on October 14, 1990-- and Lenny's memory has been active around town lately, performances, panels. But his opera's ironic setting had brought him more to life than any memory, flush with anger that the theater where "A Quiet Place" was playing had that name on it: Koch.

The New York State Theater had become The David H. Koch Theater. Did I care? So, a rich guy gave money and got his name on a building. If some board run by money heads turned a wall over to a really big money head, in an age of money heads, was it news? Then, in August, the New Yorker published Mayer's investigation of David and Charles Koch, digging into the billionaires' vast support of far right wing causes and the obnoxious tea parties, their war on environmental regulation and climate change science, their hatred of Barack Obama's administration. Mayer described the gala to honor David's $100 Million pledge to fix the old theater.

Like a few other liberal types, I was a bit of outraged at all this. But outrage passes. Shouldn't art transcend politics? When I heard about "A Quiet Place"--the first New York production, amazingly, of the opera--I bought my ticket, climbed the broad (newly redesigned) stairs, and ran into this ghost's one-man protest ..

Some who recognized Lenny argued, remonstrated--waved him off. Many seemed to master a blithe indifference, didn't lift their heads. It didn't stop him: "Hello, folks! This is an old-fashioned boycott! In the name of love and music, turn away from "A Quiet Place" at the Koch Theater. Write the board! Get that fershtinkiner name off the theater. Write them this big business daddy makes Lenny blue! Anyone who cares about this alter kocker knows those alter Kochers are bitter anathema to me. They're blasting holes in our social contract. In favor of limitless welfare for business! They are the mister misters to end all mister misters!"

When I heard that reference to the inhumane capitalist in "The Cradle Will Rock," the revolutionary piece from the 1930s written by Lenny's beloved friend (and briefly, it is said, lover) Marc Blitzstein, I knew we had a serious protest underway. Righteous Lenny was starting to persuade me. Still, I fingered my ticket, and spoke up: "Do you really want us to boycott this revival of your own opera? Did you read the reviews? It got ovations. Anthony Tommasini wrote: 'If only Bernstein could have been there to see the reaction to his opera.'"

Hearing the quote, his eyes gushed grief at me. "I'm dying that I'm doing this. Agony! Beethoven suffered deafness. Who can compare? But I dreamed of experiencing this production at Lincoln Center for Quiet..." He stopped, undone, whipped out a handkerchief, pressed it to his eyes. They brimmed again with tears. "I hear George and everyone have done beautiful work! (That would be George Steel, a former conducting student of Bernstein's who runs the New York City Opera). Lenny gripped his chest with both hands, hugging his heart. "But the world is bigger than an opera, friends. I don't ask lightly, but I ask: Don't go! Write the board! Get that name off our lovely New York State Theater!"

His face opened with an ecstatic smile, and he flung his arms around a compact man with a tough look. "This is Barry Seldes," Lenny exulted, hugging Seldes, squeezing his arm even after the bear hug was over. He said Seldes recently wrote a "terrific" book called Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician, published by the University of California Press. "Give him a copy!" he commanded the author, pointing to me, and went on exhorting opera-goers.

Seldes' book, I was stunned to see, opened at the site of the future Lincoln Center, a few feet from where we stood. It was May 14, 1959. A crowd gathered for the ground-breaking for the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

Lenny was the master of ceremonies that day. Seldes showed him conducting Copland's fanfare, introducing the guest of honor, President Dwight Eisenhower, who specifically praised people in government, labor, business, and charitable foundations who made Lincoln Center possible. After overturning the first shovelful of dirt, Eisenhower turned to shake Lenny's hand. Lincoln Center was born as a symbol of tart as a force that drives society to be its best. No wonder Lenny's ghost saw the name on that building as a betrayal.

Turning Seldes' pages, I found Lenny growing up in the Age of Roosevelt, rooted in a Jewish upbringing. Even a wunderkind from a Boston suburb couldn't escape anti-Semitism, economic collapse and echoes of war. Born in 1918, three months before the end of World War I, he was alert to red scares, the fights for workers rights, the battles against the inequalities of the early 20th Century, culminating in the Great Depression. He supported the Fascism-fighting Abraham Lincoln Brigade, helped bring early signs of the Holocaust to light. Later, Lenny joined Martin Luther King for the march on Montgomery, spoke against Vietnam.

Through the Reagan election of 1980, the rise of the conservative movement, deregulation and de-unionization, he kept going. He joined the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), took part in the AIDS fight, wrote with scorn in the New York Times of liberals who acquiesced to conservative dogma, closing their eyes to the need for better health care and other basics. He rejected George Bush's offer of a National Medal of Arts to protest cuts in federal funding for the arts.

He always strove, Seldes wrote, to defend the progressive heritage from its detractors and to shore up liberals demoralized by the conservative onslaught.

Author Barry Seldes leans against a "Quiet Place" poster," watching Leonard Bernstein's ghost urging a boycott of his opera to protest David Koch's name on the former New York State Theater.

As Seldes and I watched Lenny work the crowd, I tugged the hem of the maestro's black cape and asked about his most notorious political episode. It was a fund-raiser he held for the Black Panthers, exploited by J. Edgar Hoover, who fabricated letters denouncing him as part of Hoover's vast COINTELPRO program to destroy the movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Lenny was humiliated by a savage lampooning of the party by Tom Wolfe, in a magazine piece that coined the term "radical chic" for Leonard Bernstein and his liberal friends.

Lenny was still for a moment. "Radical chic, huh?"

He pointed at the Koch Theater and said: "Do you know they held an enormous gala for the Kochs--the cream of New York Society! They had the nerve to play my Chichester Psalms! They dressed to the teeth for the Kochs' money, the same Kochs Jane Mayer writes have intellectual kinship to people who want to get rid of the FBI and the CIA--when this country is fighting off terrorists in Times Square! Libertarians who take every oil-drilling help and tax break the government gives! Talk about radical chic! Where is Tom Wolfe when you need him!"

Lenny threw back his leonine head and howled: "Fuck Tom Wolfe!!!!!"

He reverberated with energy, lit a cigarette, took a mighty drag. It was almost curtain time at the Koch. His gaze swept over the nearly empty plaza, the stragglers rushing in to make the overture. "A lot of people walked past me," he said, plainly. "Some let me make my case. They'll notice the empty seats."

He flashed a heart-breaking smile, his eyes filling again with tears. "Hey, man, go and see my opera for me," he urged Seldes, giving one more arm squeeze. "You wrote your book. You did plenty. Jalon, no quiet place for you until you write about this noise I'm making. Say I'll be here tomorrow."

Hineni! he sang out.

And threw his hands explosively overhead, Lenny in his prime, and flew up into the evening sky.

Leonard Bernstein, the composer-conductor, who recently returned to Lincoln Center to protest against the name David H. Koch on the New York State Theater.

Photo credit: © Steve J. Sherman / www.stevejsherman.com -- Photos from the book "Leonard Bernstein At Work: His Final Years 1984-1990" by Steve J. Sherman - Amadeus Press (2010)