A year after the 1996 Olympics, I ranked twenty-third in the world in the 100-meter breaststroke and twenty-sixth in the 200-meter.

My parents did their best to shelter me from the unanimous criticism of public opinion. I didn't need anyone to tell me how bad I stunk; I knew that already. The harsh numbers of my ranking told the whole story. At least that's what I thought until I got acquainted with a whole new kind of low.

I had come into the living room of our house to find the newspaper because I wanted the movie listings; I needed to find a flick I could lose myself in. After looking on the couches and coffee table, I sat on the recliner chair where my dad read the newspaper and all of his books. I saw a piece of newsprint sticking out from in between a stack of books. Thinking it might be the paper, I lifted up the four or five volumes on top. Instead I found a hidden stash of clippings and knew immediately they were about me.

Since the start of my career, my dad was my own personal archivist, clipping any and all articles about me so that I could have them later on in life. But after carefully cutting them out, he always put them into the big red scrapbook he kept in his room.

Reading the dozen or so articles in my lap, I saw clearly why these hadn't made it into the book. Sportswriters called me fat, washed-up, and finished. I'd never do anything good in swimming again, they wrote. There it was in black and white, a complete validation of the negative voice playing on a loop in my head. It was true, I was a fat loser. The words I attacked myself with stared out at me from the page, causing a kind of sweet dread. I had suspected that everyone was talking about me, and they were. The shame -- this wasn't just a couple of mean girls at school but the whole world -- hurt so much it almost veered 180 degrees into pleasure. I wrapped myself up in sadness like a martyr, then tucked the clips back in their hiding spot so my dad wouldn't know I had found them.

I didn't talk about what was happening to me with anybody -- not my dad, mom, friends, or coach. Everyone knew that I knew I sucked, but we all ignored it. Hop into the pool, do your sets, dinner, homework, bed. Business as usual. At the time I was grateful for the normalcy. The last thing I wanted to do was draw more attention to myself. Not addressing something, however, doesn't mean it goes away.

I was completely beaten down, even if I refused to discuss it. The moment that sent me over the edge, though, had nothing to do with swimming. It started with an incident at practice. Before the team got in the pool, we always had about half an hour of training on land -- running, doing push-ups or sit-ups. On this day, Dave had come up with an exercise where we had to shimmy up a football goalpost, across the top, and then down the other side. While the girl in front of me was on the top of the goal, she lost her hold and fell. It was really scary and she ended up hurting her shoulder pretty badly.

That night, her father called my house to find out what had happened. "I want to know your side of the story of what went down," he said. I wasn't sure what he meant by "my side," but I told him what I saw.

"We were going across the football goalpost and she fell."

"I know that, but what did you do?"

"I didn't do anything."

That was all it took for this man to start screaming and cursing, blaming me for causing the accident and hurting his daughter. Even though he was a psycho swim parent, always on the pool deck talking to the coach or giving his daughter a hard time for not doing better at meets, I took his accusations to heart. He was an adult, after all. Maybe I had been going too fast, and she fell because she was nervous? Though I stayed silent as he continued to yell over the phone, a whole conversation was happening in my head.

I did it because I'm a horrible human and can't do anything right. I'm poison and now other people are getting hurt because of me.

I didn't go to swim practice for a whole week after the altercation. Nothing could overcome my embarrassment at what I had done -- not even swimming, which until then had always been my coping mechanism. Whereas in the past I could put my face in the water, not talk to anyone, and get my aggression out through energy, now the pool had become another spot of despair. My safe zone was now a place where my brain constantly battled itself. While I was trying to pretend that other things, such as the swim parent yelling at me or my horrible ranking, didn't exist or weren't such a big deal, I didn't have mental energy left over to quiet the voice berating my body. Every time I did a flip turn and felt my butt and thighs jiggle, I yelled at myself to forget it and just swim. But the next flip turn came too quickly.

So, right after the New Year in early 1997, I decided to stop training permanently. Fed up and exhausted, I had become too discouraged to fight any longer. Swimming, which I had loved so much, was now solely a source of stress and anxiety. Heading to the pool felt like a drag. I decided to give it up and become a normal high school student and do whatever normal high school students were doing.

My parents were both incredibly supportive of my decision, which wasn't a surprise. As my mom had always said, "If it's not fun anymore, stop doing it." They treated the end of my career as no big deal. More shocking was that Dave had the same attitude.

My coach, a firsthand witness to my frustration in the water, felt bad for me. I've heard horror stories of other coaches really ragging on swimmers who start tanking, but Dave never got on my case. He knew that I had been a teeny tiny thing who would one day have to grow. His giving me a hard time would do nothing to change the facts of life. Although he still acted tough in practice, at swim meets, he had a sad expression on his face, like he wished he could flip a switch and I would swim well again.

I didn't want people to pity me, so when Dave came over to my dad's house to talk to me about leaving swimming, I didn't want his concern. He didn't try to talk me into staying on the team. "I respect your wishes," he said. "If you ever want to come back, the door's open. And I want you to know that I am always here for you whether you are a Nova or not."

Despite Dave's kindness, I didn't give much in the way of a reply. I was so sick of having the swimming discussion. Can I have one conversation where people don't talk to me about swimming? It is so annoying. It's just something I do, not who I am. I'm moving on.

On my first official day as a regular teenager, I returned home from school and watched TV for four hours, until I got a headache and had to stop. In my room that night, exhausted from doing nothing, I fantasized about the cool things I was going to do with my friends now that I had all this free time. We'd probably head to Brad's house later in the week and play pool in his basement, or maybe take Lisa's Jeep out to the beach to watch the surfers.

But I discovered no one did anything fun after school. People didn't even hang out; they just returned home, did their homework, ate dinner, watched TV, and went to bed. As it turned out, being a regular teen meant sitting on the couch. A lot. The most exciting thing I did that week was to watch "Saved by the Bell" with Yvette while we were both on the phone. This was not what I thought I would be doing if I wasn't training all the time. And I definitely wasn't looking for any extra time to do homework. By week's end I was bored out of my mind.

Even worse than the boredom was the feeling that I was getting fatter. Although I wasn't working out anymore, I still maintained the same eating habits. Now when I indulged in cheeseburgers and greasy fries at lunch, the food just seemed to stick to me. My jeans started to feel tight, and flab that I'd never thought I'd see on me poked over the waistband. The guilt mounted but I didn't change my diet. If I thought I was fat before, now I was a monster. When I returned home from school, I was in a foggy state. Even though training was exhausting, it also energized me. Without any change of pace, I felt like a lazy lump.

After about a month and a half away from the pool, I realized that my levels of stress and anxiety were actually getting worse, the negative loop in my head getting louder and louder. I couldn't believe it, but I had to go back. I was like a character in one of those Lifetime movies I'd seen where the woman who is abused by her husband goes back to him because she has nowhere else to go.

I used my best tool for getting through uncomfortable situations: pretending they were no big deal. Yes, I was going to rejoin the Novas, but not as the old intense Amanda. I would use the pool as a healthy activity. I made a shift in my own mind that competing and racing trailed far behind exercising and staying in shape. Dave was equally nonchalant when I asked him if it'd be okay for me to work out at the pool again. "Sure," he said. "See you Monday."

The getting-in-shape part turned out to be harder than I imagined. In swimming, if you take a couple of days off, you feel incredibly blah in the water. After taking two months off, I needed a whole month to get back in the swing of things. Once my heart no longer felt like it was going to explode after a set, I continued to struggle. My time away had done nothing to improve my speed. The descent that had started at the end of my sophomore year followed me through my whole high school experience.

Instead of trying to regain my former fourteen-year-old glory in the breaststroke, I focused on other events, like the 100-meter freestyle, races where people weren't there to watch me and certainly didn't think I'd win. Mixing it up reduced my stress because it allowed me to hide out in plain sight.

I was way beyond worrying about the faded attention from fans and the media. The pronouncements that I was old news, which had upset me at first, also made meets easier. As expectations fell away, a sense of freedom filled its place. Without the weight of other people's opinions, I got back to improving in my own time and my own way.

With the pressure gone, my competitive juices, which had been driven down to a place hidden within me, began to run again. I started to get bored with meeting my own goals for conditioning in the pool and began to eye faster swimmers like prey. I started to race people training in the lane beside me every day, even if they didn't know it.

I kept to my program of downplaying myself and my efforts. I just want to work out and stay healthy. It was the only mode of protection I had. But in the back of my mind, I wanted to get back to the Olympics. I wasn't satisfied with what I had done as a fourteen-year-old or the idea that that one time was my only shot. I wanted to be great again.

I worried about the judgments of others, but I should have been more concerned about how hard I was on myself. Becoming good, let alone great, felt far off at best, totally unrealistic at worst. Still, I refused to give up. The wrestling match that my relationship with the water had become was not over.

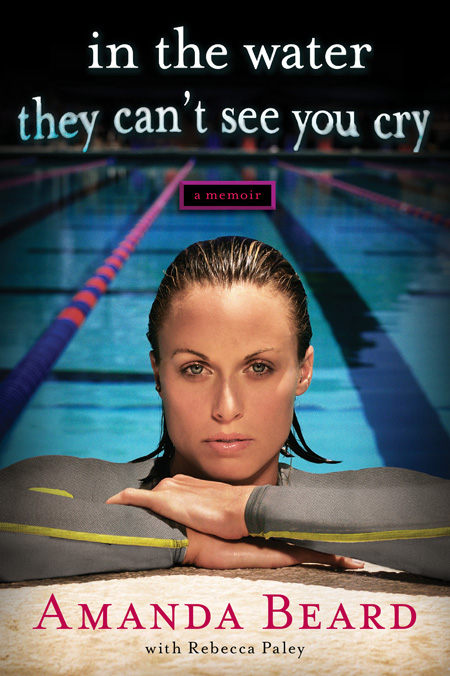

This post is excerpted from "In The Water They Can't See You Cry" (Touchstone, a division of Simon & Schuster, March 2012) by Amanda Beard.