I've really struggled with writing about this subject. How can I, as a white woman, talk about racism in a meaningful way? I have never experienced racism first-hand, and I probably never will. I am afraid to say the wrong thing the wrong way. I'm afraid to open up this terrible wound and look inside. I am terrified of being misinterpreted or misunderstood, or worse, saying something racist myself. These feelings I was experiencing lead me to the realization: We really need a better way to talk about race.

We don't talk about racism in honest terms most of the time. There is shame, anger, outrage, deep hurt, wounds that span generations upon generations, wounds you're born with, intense fear, self-loathing, hatred and despair. It's hard also to contain the conversation of race to any geographic contexts, even examining American racism. But that's probably the best place to start.

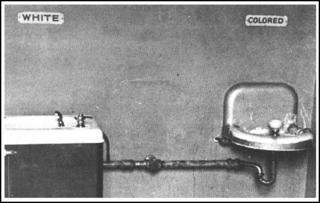

American racism is filthy, disgusting, ugly and awful. Some of the most unthinkable atrocities and human tragedies have occurred on this land. America was built upon the genocide, rape and cultural eradication of indigenous peoples, and the capture, enslavement, torture, rape, lynching and murder of black people. Centuries later, black Americans continue to be the targets of institutionalized murder, discrimination, exploitation, incarceration, poverty, appropriation and exclusion.

Some people say American racism is "getting better," but this could not be further from the truth. The manners in which racism takes form have simply changed. I've seen two creative projects that involve a white person trying to understand racism through first-hand experiences. The first is John Howard Griffin's 1961 nonfiction memoir, Black Like Me, in which Griffin uses a medical treatment for people with vitiligo to temporarily darken his skin with the intention of assuming the experience and outward perceptions of a black man in the late 1950s American South. The second is FX's 2006 reality series Black. White., which follows two families -- one black, one white -- who participate in a project to live in a house together, use makeup to present/pass as the opposite race, and document their experiences.

Both projects have some problematic premises and, in my opinion, fail to really discuss race in a useful way. In Black Like Me, Griffin writes as if he feels he has "become" a black person. The differences in how he is treated shock him to the point where he feels despair. He is denied the use of public restrooms in the white parts of town. He is followed at night by young white men, feeling afraid for his life. He hitchhikes with white strangers who ask him lewd and sexually explicit questions about his sexuality and that of black women. One white business-owner reveals that the only black women who can get a job in his company are the ones who agree to sleep with him.

Griffin seems to be shocked at this sexualization and exploitation of black women, but overall the book is very sexist. He only discusses race in terms of its effects on black men (who he begins to view as peers) and children (who he relates to as a father). In one chapter (I highlighted it) he introduces a colleague as, "Dr. Moreland (Mrs. Charles Moreland)." God forbid we don't associated her with a man, or believe simply from his subsequent feminine pronoun use that a woman can be a doctor. He seems earnest, however, in wanting to try to figure out a solution to racism, and appears to form genuine connections within the black communities he visits.

But a white man who steps momentarily out of his privilege by assuming brown skin in no way makes him "become" a person of color. Experiencing racism for a month or two doesn't give you the understanding that a lifetime of racism does. The book pleads a white case for civil rights because it came from a white man. There were peeks of insight into the black American experience, but they were limited by the ignorance that begets a man putting on a costume with the belief that he could possibly understand (or solve) racism.

Black. White. at least invites the first-hand experiences of black people into the dialogue. The show itself is a mixed bag. There are moments of insight and intelligent discussion, and there are moments that unabashedly reinforce racial stereotypes. The black family generally views their experiences within the project as a validation of their existing perceptions about racism in America. None of this is news to them, and of course as black Americans, they already understand the ways racism takes form first-hand.

When the white family takes on the black appearance, lots of cringe-worthy racist antics ensue. The mom picks a dashiki as her outfit for church on Sunday, and asks to touch a woman's hair at the beauty salon. It's clear that she has exoticized black culture to the point that she really doesn't understand anything genuine about it. Confronted with her own racism, she becomes frustrated and feels attacked for having offended the mother of the other family.

There was an opportunity here to use these instances as teaching moments, but the family, legitimately offended, gave up on a dialogue with the woman. I think there are a lot of people like her who have learned racist behaviors and assumptions through osmosis, and would be very hurt if called a racist. It's clear from the way we use the word that racism is negative and ugly, and of course no one wants to be associated with that. But you need to talk about the ways racism affects you in order to see it, understand it and grow from it. There is racism that is explicit, but there is also unaware and internalized racism, and those forms of racism need to be talked about in order to heal and change.

So what can these works tell us, and what can we do better? I think they tell us that there are white people who are tremendously fearful of black people, based on assumptions and judgments that are learned and felt -- whether consciously or not -- on a deep level. I think this fear leads people to not really see a person in front of them -- that they are only able to see "blackness." When this happens, the fears are projected onto and attributed to any black person's behavior. Suddenly a person looking for help looks like someone trying to break into a house. A smile from a stranger on the subway seems to whisper "I'm going to hurt you," in someone's ear.

In September, a 24-year-old man was shot 10 times by police who were called after the young man knocked on a residential front door, seeking help after being in a car accident in Charlotte, North Carolina. In November, a 19-year-old woman was shot in the head by a civilian for knocking on their front door, who had also been seeking help after a car accident in Detroit, Michigan. Reading further into this story, I found this article on a report released by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement that reveals every 28 hours, a black American is allegedly extra-judicially executed by U.S. law enforcement, security guards and/or vigilantes.

This is something we all should find deeply troubling. This is something we should all be talking about and fighting to change. When black teenagers are shot down by police, it is because of racism, not that they were "acting suspicious." We cannot stand for these things to be covered up or explained away. We're talking about murder, and we all need to confront our own racism so we can break this horrible cycle.

Understanding racism doesn't come from putting on black face and seeing how you're treated. Solving racism isn't going to come from experiencing it in small doses. Solving racism, or at least talking about solving racism, needs to come from white people being honest in the examination of their own racist attitudes, perceptions and behaviors. We have tried and failed to understand at a critical level what experiencing racism feels like. Now, we need to try to discuss what being racist -- in all its forms -- feels like.