South Philly is well known for its Italian food. But turns out Italians may not have been the first to bring the Mediterranean diet to the city. AFR contributor Amanda Moniz tells all.

When I was in graduate school researching newspapers from the 1780s and '90s, I was surprised to find Philadelphia merchants advertising olive oil, capers and anchovies. Who ate these foods, I wondered, and what did they make with them? These and other Mediterranean foods, I learned, were Jewish contributions to American cuisine.

The earliest Jews in North America had Iberian roots - their ancestors had either been expelled from Iberia (Spain or Portugal) or had formally converted to Christianity and practiced Judaism secretly. Jewish cuisine in Britain and its North American colonies reflected this Iberian heritage and was familiar enough that one of the leading 18th-century British cookbooks includes several recipes for dishes "Jews way.'"

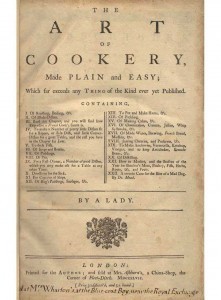

Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, first published in England in 1747, was the most popular cookbook in both 18th-century Britain and America. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owned copies, and Benjamin Franklin liked the book's recipes enough to translate some into French, perhaps to make sure that while he was on his diplomatic trips to Paris in the 1760s and '70s, someone would know how to cook properly.

Glasse's extensive cookbook includes recipes for roasting pig, lamb, geese, rabbits, tongue, udder and more. She offers sauces for turkey, ducks, larks and venison. She tells readers how to "dress" cauliflower, French beans, artichokes and "brockala." And those are just a very few recipes from the first page and a half of an 18-page table of contents. There are recipes for regional English specialties, such as Devonshire squab pie and for foreign dishes such as "beans the German way" and "haddocks the Spanish way."

The Art of Cookery also recognized a distinct Jewish culinary influence. The 1760 edition includes six recipes for dishes prepared in a Jewish style: "haddocks the Jews way," "The Jews way of preserving salmon, and all sorts of fish," "marmalade of eggs the Jews way," "To stew green peas the Jews way," "English Jews puddings; an excellent dish for six or seven people, for the expense of six pence" and "The Jews way to pickle beef, which will go good to the West Indies, and keep a year good in the pickle, and with care will go to the East Indies."

Although some of these dishes share much with Spanish cuisine - which was much influenced by Arab culinary traditions - Glasse distinguished between Spanish and Jewish dishes. Her Spanish-style haddock recipes calls for the fish to be broiled, then seasoned with mace, cloves, nutmeg, garlic and tomatoes, and then stewed. The Jewish-style haddock is seasoned with mace, no cloves or nutmeg, and calls for onion, not garlic. The fish is poached lightly and then finished with an egg-lemon sauce. The recipes differ, but the distinction between Spanish and Jewish cuisines also reflects the era's common view that Jews were a distinct nation.

The Art of Cookery's recipes for "English Jews pudding" and for Jewish-style pickled beef offer contrasting perceptions of Jewish life. The pudding, made with offal seasoned with onion, spices, lemon zest and parsley, is an economy dish. Although Glasse comments that it "is a very good dish," she implies that those with a choice might pick other food when she notes this dish is "a fine thing for poor people."

If the pudding recipe suggests Jews knew want, the pickled beef highlights a view of Jews as a trading people. Indeed, Jews - like other marginal people, such as Quakers and Scots, in the British world - were able to use their communal ties around the Atlantic to build trading networks. The late 1600s to mid-1700s saw marked hostility to Anglo-American Jewish merchants, who English merchants saw as competitors.

Glasse's recipe for pickled beef does not reveal any animosity to Jews as traders. On the contrary, it suggests Jews had useful knowledge others might benefit from. It would be going too far to say that "pickled beef the Jews way" tells a story of British acceptance of Jews, but The Art of Cookery does reveal that Jewish cuisine was more widely familiar than I, for one, would have guessed.

-- Amanda Moniz