America's Promise Alliance published a new study this fall, Don't Quit On Me, and invited young people to share their perspectives about the support that at-risk youth really need to graduate from high school. For more youth stories like the one below, visit Ola's story, Amnoni's story and Ti'Andre's story.

If you want to share your story--or know someone who does--email Eva Harder at evah@americaspromise.org.

by: Stephanie Watkins-Cruz

The first time my parents were evicted from their house, I was a junior in high school.

It was the Monday after junior prom, and I came home to the yellow eviction notice on our front door. My mom was crying, and our living room was filled with boxes.

Shortly after that, we moved into a Quality Inn hotel. We lived there for two months.

Until that point, I had always been a good student. I got good grades, was involved with extracurriculars and had good relationships with friends and teachers. But the minute I saw that eviction notice, I was filled with fear.

What were we going to do? How would I ever be able to afford college?

An Almost Success Story

Luckily, I inherited my parents' stubbornness and a steel resolve to finish high school and ultimately go to college. But I also had something else, something I never would have survived without: dance, and the network of teachers, friends, parents and mentors I met as a result.

Dance quickly became my escape. It was a different world, it was a safe haven where I just had to stretch further and jump higher. It wasn't a Quality Inn, it wasn't a Best Western. And the people I met through dance encouraged me every day without even knowing what I was going through.

Dance was always there for me, and I've seen it do the same for other kids. So when I heard that programs like my middle school dance program at Piedmont Middle were being cut, my heart broke for all the kids that would have to find another escape, at the risk of missing out on finding one right when they need it most.

Overcoming the first eviction cannot be accredited to a single source of strength for me. I don't believe that it was just my teachers that got me through or just my resolve, or even dance. It was the collaboration of the three, and without one of the parts, I know the risk of me not getting to college or maybe even finishing high school would have been that much higher. And I wouldn't be where I am now.

This past May, I graduated with my Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of North Carolina at Asheville. This past August, I started a master's program in Public Administration at the School of Government at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

It's been five years since the first eviction.

I now live in my own apartment. And in many ways, my story reads like a success story. But the truth is, it isn't finished.

Almost four years ago, my parents were evicted from their home again. And for a second time, they had to pack up their home, and move into a Best Western--where they continue to live to this day.

'Upper' Middle Class and Transitionally Homeless

My parents both work hard, they go to work every day, and some days it's all day.

According to Pew Research Center, my parents - ironically - aren't just middle class--they're considered 'upper' middle class. Clearly, middle class distinctions aren't as valid and clear cut as they used to be, because in reality, my parents are essentially transitionally homeless.

It costs more to live in a hotel than it does to rent a decent apartment in Charlotte, North Carolina. But my parents have a poor credit history and two evictions behind them; this means landlords require a two-month deposit upfront--that's $2500 before you even move in, or about two months rent at a Best Western.

If all the money is going to car payments, health bills, food and expensive rent, how can you afford to pay for the option that's supposed to be cheaper in the first place?

When I think about what needs to change to help families like mine, a million thoughts race through my head. The main one however, is that there needs to be a policy for when life happens.

My parents can't afford a home because there is no room for life when it comes to housing policies. We're above a certain line of income, so we don't qualify for help. We pay rent well over the rent we used to pay before being evicted, but in order to prove that we can have a home again we would have to pay almost triple the amount. Furthermore, we would be left with virtually no money for moving, furniture, food, and other basic necessities.

There are two policies that could help the situation if they were just tweaked or changed. First, we could expand HUD housing choice voucher program to accommodate more individuals under a new income level (slightly higher than low-income) and collaborate with different organizations or programs to supplement that expansion and allow individuals to find their own homes at a subsidized rate.

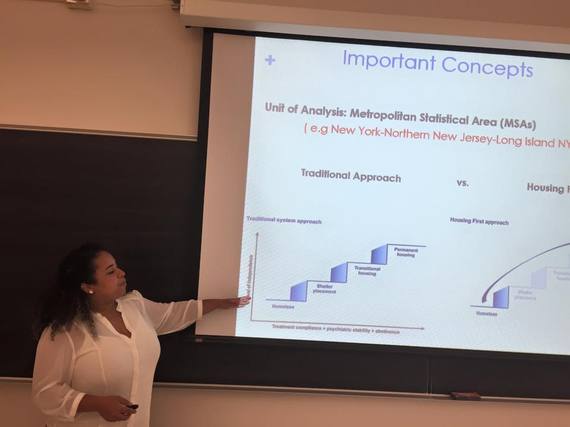

Second, we could apply the Housing First philosophy to people who have been evicted and require each apartment complex to have 10-15 units that are committed to helping transition individuals or families into renting responsibly again.

We could ease people back into renting, and even require a financial literacy course or program with a nearby bank.

It's not a handout; it's a learning opportunity. More importantly, it's the chance to give people and families a home again. And instead of punishing them for life happening, show them the way to get back up and keep going.

Stephanie Watkins-Cruz is a Charlotte, North Carolina native and a youth board member at America's Promise Alliance. She is currently pursuing a Master's of Public Administration with an intended focus on community and economic development at the School of Government at UNC Chapel Hill. Watkins-Cruz hopes to one day work for a government or non-profit organization that creates affordable housing opportunities for individuals and families all along the spectrum of need.