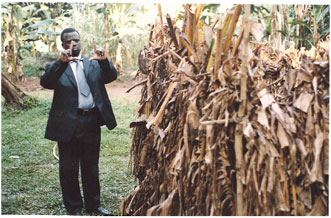

"If we don't tell our stories, no one else will." That is the mantra of Maisha (meaning life in Kiswahili), the non-profit filmmakers' training program based in Kampala, Uganda that I've worked for since 2004. Each year Maisha conducts three-week training labs for aspiring East African film professionals in directing, screenwriting, sound recording, cinematography, and editing. Founded by filmmaker Mira Nair (Monsoon Wedding, The Namesake), Maisha brings filmmaking professionals from all over the world to Kampala to mentor students from Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Kenya. Rather than attempt to "doctor" participants' work or guide it in a particular direction, the lab's goal is to equip our students with the tools necessary to articulate their unique visions on screen.

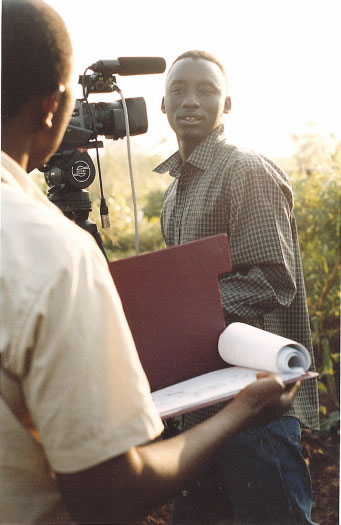

In our third year of operation, Maisha has grown from a summer program to a year-round one, thus allowing us to train more people. Our most recent session, which started on July 26th, welcomed nine filmmaking trainees. The participants were selected based on their submitted screenplays and sent into a rigorous week of supervised revision under the experienced and meticulous eyes of Joshua Marston (Writer/Director, Maria Full of Grace), Jason Filardi (Writer, Bringing Down the House), Alison Maclean (Director, Jesus' Son), and David Keating (Writer/Director, The Last of the High Kings).

After these first seven days, the mentors sat down and deliberated to choose three of the nine films to go into production, with the remaining six filmmakers serving as production managers and assistant directors. We also welcomed a new branch of participants -- three cinematographers, three sound mixers, and three editors -- who would train with their own respective mentors: Barry Alexander Brown (Editor, Malcolm X, Inside Man), Kerwin DeVonish (2nd Unit DP, Inside Man), Fellipe Barbosa (Writer/Director, Salt Kiss), Verane Pick (Actress, Last Looks), and Drew Kunin (Sound Mixer, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon). Three six-person crews were then assembled and given three days to shoot, and three days to edit their short films.

The three films that were created at the 2007 Maisha lab -- Must Be A God-Fearing Christian Girl by Wanjiru Kairu from Kenya, The Trip by James Gayo from Tanzania, and What Happened in Room 13 by Dilman Dila from Uganda -- were, in my opinion, examples of a very pure brand of cinema. All three of these filmmakers had the craft in their blood without seeing even a fraction of the films a student the States would have. Though the stories range from a comedy about a young man whose mother tries to guilt him into marriage to a silent film about a philandering husband they have in common specifically local themes- which is what, in Mira Nair's words, makes them so "surprisingly universal."

The birth of a training program is an education in itself, especially in a region where funding arts and culture is not a priority and there is literally no infrastructure for filmmaking and distribution. Even so, all of the Maisha students, past, present, and future, are working filmmakers. While people in other parts of the world have the opportunity to go to school to study filmmaking, these individuals are doing it entirely on their own. It's baptism by fire and it's the tenacity of the students to get their work made and seen that drives Maisha. The organization simply exists to supply guidance, support, and exposure.

When asked about why she has undertaken the task of running the program, Maisha's Program Director, Tanzanian-born Musarait Kashmiri jokingly says, "I think that Africa needs a serious PR makeover." As much as I agree, I don't want to write about my opinions on the media's portrayal of "Africa" -- or even comment on the common assumption that a collective voice exists for an entire continent. I'd rather leave that to the men and women who are creating raw, beautiful films in East Africa. They don't function as ambassadors of their culture or beholden bearers of truth, but as true, passionate artists of the highest order.

Even though the quality of the work that's coming out of Maisha is exceptionally solid, there remains the question of distribution. While independent filmmakers in any other part of the world have access to a network of distributors, festivals, and cinemas, East African filmmakers do not. I recently viewed a film made by Ugandan directing collective Yes That's Us. Filmmaker Donald Mugisha and his partners recruited Ugandan reggae superstars Bobi Wine and Buchaman to star in their debut feature film, Divizionz, a sophisticated yet honest portrayal of life in the Kampala ghetto shot on HD. Donald confessed to me that he had sunk about $8,000 USD of his own money into the project, but now that it's complete, he is having a hard time figuring out what to do with it. It's not as though a distribution company is going to buy the rights and show it in the few East African multiplexes, where Jet Li reigns supreme. Donald's best hope at this moment is to show the film at local festivals (where, unlike the States, films are rarely bought) but after that, how will Yes That's Us continue to thrive? Donald's quandary is a common lament of any director in a region with a nascent film industry.

Maisha is in the process of sending the 2007 short films out to both East African and international film festivals. We are developing an internet-based post-lab support program where Maisha alumni can upload their work and send it to their mentors for feedback. With digital technology, filmmaking is more accessible and mobile, and certainly more viral. And of course, we're always accepting applications for our programs. Now that these stories are being told, we need to make sure they are being heard so that these exciting new voices can make the impact they are so deeply capable of.