My new study addresses the longstanding debate about whether international sporting events make countries more peaceful or violent. To tackle this question, I compare the aggression levels of countries that barely made and barely missed qualification for the World Cup. I focus on these countries because they provide us with a natural experiment. The idea is that when countries barely qualify and barely fall short, it is basically a coin flip which ones go to the World Cup. This type of natural experiment is called a regression discontinuity, and many statisticians consider it to be one of the best ways to identify a causal relationship with observational data.

After researching the entire history of the World Cup, I found 142 countries that barely made or barely missed qualification. The qualifier and non-qualifier groups are very similar across many factors, including their historical records of aggression. To measure aggression, I used the number of Militarized Interstate Disputes that each country initiated, which is the standard measure of state aggression in political science. These disputes are cases where states explicitly threaten, display, or use force against other countries. This measure is commonly used in security studies, since full-scale wars happen too rarely to be a useful measure in most statistical tests.

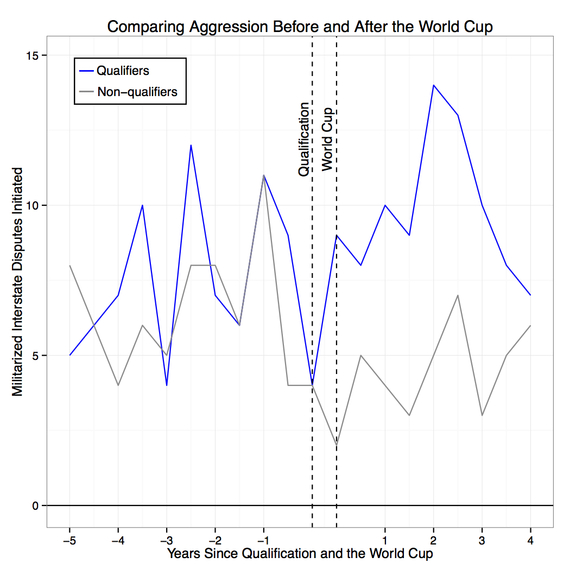

The results provide strong evidence that the World Cup increases international conflict. As the graph below shows, the qualifiers experienced a large spike in military aggression during the World Cup year. The difference in the aggression levels of the two groups is statistically significant, and the probability of seeing a divergence this large by chance is less than one in 150. The estimated treatment effect is also much larger for countries where soccer is the most popular sport. In fact, countries like the United States where soccer is not the most popular sport experienced no change in aggression after going to the World Cup.

The results also suggest that the World Cup has a larger effect on authoritarian states than democracies. The estimates indicate that authoritarian countries became about twice as aggressive because of the World Cup, whereas democracies experienced an increase in aggression about half as large. This finding is consistent with a number of cases suggesting that sports are more closely linked to state power and legitimacy in non-democracies. For instance, authoritarian countries tend to devote much more money to their national sports teams than democracies, and many have state-run sports academies where athletes are trained from young ages to bring glory to their countries. Thus, when non-democracies make it to the World Cup, it is usually easier for their leaders to claim credit for this success and use it to incite hyper-nationalism.

Can this research strategy be used to show that other sporting events also increase international conflict? After all, there are plenty of examples that suggest that they do. Unfortunately, most other major sporting events like the Olympics do not have qualification processes that result in many countries barely qualifying and barely falling short. However, the FIFA regional soccer championships, like the Asian Cup and African Cup of Nations, do have the same qualification format. Therefore, I was able to investigate how these tournaments affect state aggression in my paper. I again found that the qualifiers and non-qualifiers were very similar across many factors prior to qualification, but that the qualifiers became significantly more aggressive when they went to their regional tournaments. Also like before, the estimated effect was much larger for authoritarian states than democracies. A full summary of these results can be found in my paper.

In short, my findings provide strong evidence that soccer makes international conflict worse. This is an idea that has been advanced by many reporters and scholars going back to Orwell, and it is well-illustrated by cases like the 1969 Football War between El Salvador and Honduras, the 1991 Croatian War of Independence, and the 2009 Egypt-Algeria World Cup Dispute. No doubt, over the next month we will hear many politicians and celebrities praise the ability of sports to unite the world. In my view, this is nothing more than wishful thinking. Pitting countries against each other on the world stage is almost certain to do more harm than good for international relations.