Below is an excerpt from my recent essay, "Give Me The Gun," in the current issue of Boom: A Journal of California. It is a mediation of life in exile, trauma, and inherited memories; and it is an effort to understand the reasons behind the violence committed by the Tsarnaev brothers a year ago in Boston during its annual marathon.

I am now seven years older than my father was when he came to California at the end of the Vietnam War. I have been an American writer and journalist for over two decades. I am here to tell you that the war, though it ended so long ago, doesn't end -- and for children from war-torn countries, the Old World, its memories and turmoil, sometimes calls out for our blood.

For years I've had this dream: Sometimes I'm a bird, other times I'm fully human. Always it's a dive into the ocean. Bird, me as a child, as an adult -- no matter, in the dream, it's straight to the bottom I go. With bloody fingers, with a scratched beak, I try to excavate, to retrieve something hard to see.

There it is: a gun. In the dream, it turns into a vague object, or a sorry-looking rock, or it changes its shape continuously and loses texture -- or else the gun dissolves into sand, into mud, and sifts through my clutching fingers.

Some dreams are impossible to decipher; but this one is a direct route to my own psyche. Upon news that the South Vietnamese government had surrendered to the communist invasion, my father boarded a naval ship with a few hundred other Vietnamese officials and their families on the Saigon River and headed out to sea. Nearing Subic Bay in the Philippines where they asked US authorities for asylum, he folded away his army uniform, changed into a pair of jeans and a shirt, and, now a stateless man, tossed his gun into the water.

I was not there. I was already in Guam, having left inside a humming C-130 cargo plane full of panicked refugees out of Tan Son Nhat Airport two days before Saigon fell, but I've come to regard that moment when he jettisoned his gun into the sea as a turning point in my own story. Rusting at the sandy bottom, it serves as a kind of marker. It spelled the end of my Vietnamese childhood and the beginning of my life in exile in America.

I am telling you this because although I fail to retrieve that gun in my dreams, I am all too aware that some other refugee children in America have managed to grab hold of it in reality, and on a few occasions have even found their way toward tragedy. The rags-to-riches American immigrant narrative often fails to acknowledge its darker stepsister, a chronicle in which some children, failing to fulfill their American dream, revert to fight lost battles from their parents' homeland.

I am telling you this because I am still trying to understand what happened when two bombs went off and killed three people at the Boston Marathon and seriously wounded dozens of others.

The culprits were not organized terrorists, not foreigners, but two Chechen brothers who, on their way to the American Dream, crashed into a bloodbath of their own making. Tamerlan Tsarnaev, 26, and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, 19, lived for years in Boston. Both were once refugees and, along with their parents and two sisters, found asylum in America; both were known to friends and neighbors as "regular guys," which makes their bloody sagas all the more baffling and disturbing.

In watching their stories unfold, I couldn't help but wonder how much of a scar does being a child of a war-torn country leave? And why do some old scars turn back into open, festering wounds?

Here is what we know: Tamerlan was an aspiring boxer who dropped out of school and was described by others as "cool" and "arrogant." He represented New England in the 2009 Golden Gloves national championship but could not compete the following year when rule changes barred non-US citizens. That, coupled with a back injury, killed his Olympic dream, his vision of a better world. It was around this time when his life veered hard toward radical Islam and fundamentalism.

Dzhokhar, the younger brother -- who, ironically, became a US citizen on September 11, 2012 -- was reportedly likable and outgoing. A wrestler who attended Boston Dartmouth, Dzhokhar was struggling. He received seven failing grades over three semesters, including Fs in chemistry and Introduction to American Politics. He had $20,000 in unpaid bills to the university at the time of his arrest.

Their family, too, had unraveled. Anzor, their father, was a mechanic; Zubeidat, their mother who had turned religious and reportedly had a great deal of influence on Tamerlan, worked as a cosmetologist. Both suffered setbacks in America, went on welfare after a few years of working, and then divorced. Anzor moved back to Dagestan, east of Chechnya, to be followed by Zubeidat a few years later. They had left Tamerlan in charge of his younger brother. Two middle sisters had moved to New York and kept their distance.

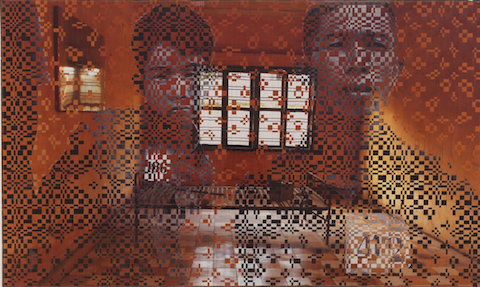

My Father's ARVN Army Hat and Cane

Here is what I think: It is inevitable that children born into war inherit trauma, even if they didn't experience that war firsthand. The inheritance is deep rooted, and it seeps in below the surface: the way the adults talk of the past, the way fragments of their history replay on TV, the way sadness hangs in the refugee home like heavy air, like smoke; a lost home, a shattered people, the humiliation, the overwhelming nostalgia; it seeps into dreams. And when they are vulnerable, when their lives in America unravel and their access to America's grandeur is blocked and denied, the old memories and unshaped desires have a way of reaching out to take hold.

The late UC Berkeley sociologist Franz Schurmann once noted two paths for children of immigrants toward their Americanization process: either through education or the military. But there's no longer a draft, and the other institution, the American education system, is failing our kids.

One of the Tsarnaevs' uncles, a successful man in America, when asked for an explanation of their actions, described them as "losers" who harbored a hatred of those who were able to settle into life in America. "These are the only reasons I can imagine. Anything else, anything else to do with religion, with Islam, it's a fraud, it's a fake," he said.

The uncle may not be far from the truth. Islam may very well become the old clutch when the brothers' vision of a beatific America falters. Unable to move forward, they move back, trying to become warriors for a lost cause, or trying to assuage their parents' humiliation and grief. Or else, they try to find a theater on which they can still play out as the main actors.

Though I have moved far away from my humble beginning, have found a direction for myself, and have in many ways betrayed my allegiance to the old country, I never underestimate the speed with which a refugee boy can go off track -- how the vision of America as the land of milk and honey can quickly shift to that of a bona fide barren landscape with a failing grade. Ambition, too, can shift to rage and hatred, and the "mixing memory and desire," to quote T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land, can like the spring rain stir all "dull roots."

Read the rest of the piece @ Boom: A Journal of California

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and author of the "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora," and "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres." His latest book is "Birds of Paradise Lost," a short story collection, was published in 2013 and won a Pen/Josephine Miles Literary Award in 2014 and shortlisted for the California Book Award.