No one likes to be told how to feel. And right now, Chicagoans feel afraid. A recent uptick in homicides and shootings has created a national buzz around the levels of violence in the Windy City. Academics like to point out that in historical terms, homicides in 2010 reached a nearly 40-year low and that it's way too early to tell if the recent surge in violence is anything more than "normal variation" in the larger violence trend. Statistically speaking, we are much safer than we've been in a generation.

Statistics don't make people "feel" safer, though. And, let's be honest, no one likes to listen to professors anyway. People's gut reaction is based on their experiences -- what they hear, read, see and live as they go about their daily routines. Few of us care about historical crime statistics. We care about what's happening in the here and now.

The discrepancy between the reality of the numbers and the reality of lived experience raises a critical question. If we are at a low point in a longer history of violence, why don't people feel safe? The answer, to borrow a phrase, is: it's the gangs, stupid. Much of the reason people don't feel as safe as they perhaps should feel has to do with the extent and nature of gang violence.

Not all crime is alike. The nation as a whole is experiencing what some criminologists call the "Great Crime Decline" -- record decreases in violent crime we haven't seen since before the Vietnam War. During the height of the so-called "Crack Era" the number of homicides in Chicago teetered around 900. Over the past five years, that number has been around 400 a year, representing a steep 50 percent decline.

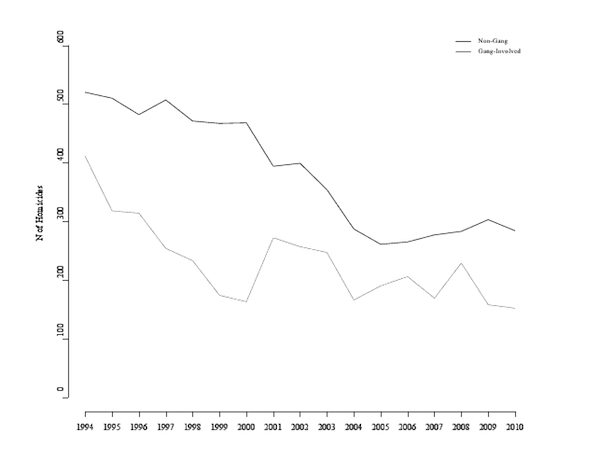

Nonetheless rates of gang homicide remain stubbornly stable in the midst of this larger drop. Take a look at the figure below, which plots the number of gang-involved and non-gang homicides from 1994 (the height of the Crack Epidemic) to 2010. Consistent with the nation-wide trend, non-gang homicides fall continuously over this entire period. In contrast, even though gang homicides fell rapidly during the early part of this period, the absolute number of gang homicides has not changed much over the last decade.

The Number of Gang-Involved and Non-Gang Involved Homicides in Chicago, 1994

to 2010

What this trend shows is that today the homicide problem in Chicago is mainly a gang problem. Even the slightest change in gangs and gang violence -- be it a conflict over a drug corner, an internal family-style disagreement, or the result of pesky name-calling -- has the potential to move the city's overall rate of violence.

More than that, though, gang homicide is different than other types of homicide. Gang homicides are more likely to involve a gun, more likely to occur in public (especially on the street), more likely to involve a greater number of victims and offenders, and more likely to spark retaliation. Gang violence is also more likely to cause collateral damage, such as a stray bullet killing an innocent victim. In short, people are much more likely to hear, see, and react to gang homicides as compared, say, to those homicides that happen behind closed doors. All of this fuels our fear of gangs and makes us feel less say that statistics would otherwise tell us.

So what should we do? Any loss of life is tragic and the recent spike in violence is perhaps a call to action. Still, action and not reaction is the best approach. With less of "other" types of violence, it's time to retool, rethink, and reboot our approaches to gang violence. In the long term, this entails improving the social, economic, and educational opportunities in our most disadvantaged neighborhoods. If we want to break cycles of violence, we need to address the underlying and enduring causes.

In the short term, reducing violence means getting a grip on the exact nature of gang disputes in the here-and-now and intervening accordingly. Short-term violence reduction efforts are best served not by vague references to a "gang problem," but by understanding the exact groups and individuals involved in the disputes and, more importantly, using such information to mediate such disputes before they escalate. For example, if the Tough Guy Gang has been shooting at the Nice Guy Gang, resources should directed towards those groups -- the one's involved in violence -- as opposed to some more general strategy towards gangs writ large that might catch-up individuals who are not part of the present and specific violence. The latter approach, while not without its own merit, simply detracts resources and attention away from the groups and individuals immediately involved in gang disputes.

The goods news is -- if there is any good news in all of this -- is that the city as a whole is moving in the right direction. The Police Department has made massive strides in re-directing its resources in exactly such a fashion with its use of social network analysis as a new crime-fighting tool. Likewise, efforts by the Chicago Violence Reduction Strategy are directly engaging such violent conflicts by mapping gang disputes and directing prevention efforts accordingly. And, violence interrupters from Cure Violence and outreach workers from dozens of less well-known organizations use such an approach almost instinctually. The hope is that such a targeted approach towards understanding gang violence can continue to lower Chicago's crime rate. And, it is only such hope that will reduce our fear of (gang) crime.