Dr. Lawrence "Rusty" Hofmann faced a nightmare no parent would wish even on their greatest enemy: losing their child to a disease that no doctor could identify, much less treat.

After a swim in California's Monterey Bay, his son Grady's eyes appeared yellow, a sign of possible liver failure. Dr. Hofmann, who is chief of interventional radiology at Stanford University, thought there was no way his always-healthy son could possibly be sick.

However, watching and observing, Dr. Hofmann knew something was wrong, so he and his wife rushed their eight-year-old to the hospital. It turns out the boy had extremely high levels of a toxin called bilirubin, and his liver was not processing it.

His son was put on observation for a week, but every day the levels of bilirubin got higher. Dr. Hofmann called in specialists in the areas of immunology, liver transplantation, and infectious disease, who, at first, could not figure out why Grady was rapidly deteriorating. "He was going to go into liver failure if they didn't figure out what was wrong with him," said Dr. Hofmann.

After extensive tests, the doctors eventually figured that Grady was having an immune reaction in his liver, and managed it with medication. It turns out that Grady had the subtype of literally a "one in a million" disease, called aplastic anemia, which exhibits itself as a liver infection and an immune response.

Grady improved for many months, but had another complication months later -- bone marrow failure. His body simply stopped making red blood cells. "Holy cow, this is a life threatening illness," said Dr. Hofmann, who knew that his son could die and likely wouldn't survive without a bone marrow transplant.

Bone marrow donors are usually siblings; in this case the donor match was the parent -- Dr. Hofmann -- an extremely rare situation with great risk of complication. The choice was to either give Grady a transplant from his father, or for him to take immunosuppressant drugs, putting him at risk from the outside world.

"I didn't know what the right answer was," said Dr. Hofmann, who began calling experts around the country. "I spoke to the most experienced people on the planet -- even the National Institutes of Health (NIH), who called me within two hours." The NIH said that even with treatment, his son had a 50/50 chance of living.

Dr. Hofmann knew a second opinion was critical, so he called a doctor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Institute in Seattle, where transplanting bone marrow was invented. The doctor advised him to go forward with the stem cell transplant, and gave him access to a yet-unpublished article from the New England Journal of Medicine. It gave Dr. Hofmann the ammunition he needed to make a decision; go for the transplant, despite the risks.

Grady's ninth birthday party was the day before the procedure. "As I watched my son blow out the candles, I said 'I hope he makes it to ten.' It was the worst birthday party I had ever been to in my life," said Dr. Hofmann.

Grady received his father's cells and was in isolation so his immune system could recover. After a month, his son returned home. Fast forward, three years later, Grady is now a healthy, happy, and thriving 12-year-old.

A TURNING POINT

"I became a faculty member at Stanford to change medicine but it was my son who did it, not me," said Dr. Hofmann, who realized his son's brush with death was a turning point. Dr. Hofmann recognized he was able to save his son's life simply because he had access to the best knowledge in the world. Most people are not lucky enough to have contacts and know-how to navigate the complexities of the health care system, and this seemed like an inherent injustice. Dr. Hofmann thought he could solve this imbalance by offering patients the same kind of expert opinion that he got.

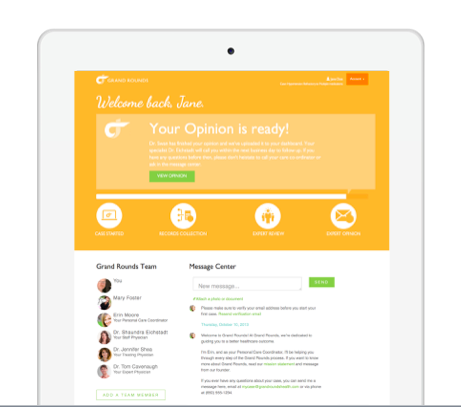

And so Grand Rounds, a health technology company, was born. The company's goal is simple: democratize medical care and give clients expert opinions from the world's leading doctors, the type that helped save his son's life.

The company offers expert opinions, as well as something else called visits. For an expert opinion, Grand Rounds matches the patient with a doctor who specializes in their condition, even if the two do not live in the same city. The doctor logs into the Grand Rounds platform as all records have been uploaded to the cloud, and then analyzes the situation. Written opinions are given almost immediately. For a visit, Grand Rounds matches patients with the top physician who practices in the area where the patient lives.

The business model is remarkably simple. Grand Round charges a few dollars per employee per month, and depending on whether the employee accesses a top physician remotely or locally, it costs nothing, or it is covered by existing insurance. Considering that many patients must visit several doctors to finally get the right treatment for whatever ails them, Grand Rounds might just be the bargain that the benefits department of companies are looking for. Although the primary focus is larger employers, individuals are able to sign up for the service too.

"Everybody wins," said Joseph Ansanelli, investor and a partner at venture firm Greylock Partners who is also on Grand Rounds' board of directors. "The interesting thing is that employees love it and get world-class care. They get an advocate on how to navigate the health care system, and employers love it as it reduces the cost of care," he said,

On average, Grand Rounds saves between $2,000 and $10,000 per case, and drives better outcomes. This is on average -- because once in awhile a single case can save hundreds of thousands of dollars. Ansanelli notes that this is a powerful combination for health care. "Saving money and providing better care seems counterintuitive. Finding a world-class doctor will save you money," he said.

"There is a fundamental microeconomic story of the company," said co-founder Owen Tripp. "When you get bad care, it's not just the poor result that costs society a lot, it is the repeated missing of work, overuse of medication, and time off for many appointments. This is yoking our industry in the US," he said, adding that there is not one company that Grand Rounds has spoken to that is not worried about their health care costs.

Given the role of big data today, it is not surprising that the company chomps away through massive data sets in order to find what is predictive about physician quality. Consider what happened before the use of data: providers in the system would see a backwash of poorly treated patients but would not know why. But big data reveals the secrets of the system. Stats are available on small details; for example, if a test is not being ordered for a patient, or other deficiencies in the system.

"We can deduce where quality exists and where it doesn't," said Tripp, adding that medical professionals can often mistreat or undertreat conditions because they don't have the seasoned experience of a specialist. The mission of Grand Rounds is to become medical insiders, but to do it at scale," said Tripp.

PATIENT'S REACTIONS

The company is obviously good at the patient experience. "While we wanted great software and a mobile app, in health care patients don't want to interact with an Android phone," said Tripp. "They want to say, I know Claire at Grand Rounds."

Luke Prettol, Human Capital Manager at Aggreko, a multinational provider of rental power, heating and cooling equipment, chose Grand Rounds for his firm when he saw that medical claims were rising at an alarming rate. "We found out that one problem was orthopedic surgeries with no second opinion, and another was very complicated, unique conditions with a lot of testing going on. We asked ourselves if the employees were getting the best care," he said.

What impressed him was the value that Grand Rounds brought to patients. "You have the ability to have a concierge coordinate everything you are doing from a health perspective - getting a new doctor, records collection, and second opinions. The best analogy is of one of my employees who was very scared because he needed a surgery that would potentially impact his career. He could not say enough good things about his experience with Grand Rounds," Prettol said. He added an analogy, saying that using Grand Rounds was like flying in a private jet.

When a patient comes to the company, they are immediately on a journey that begins with a team, including a records specialist who ensures all the patient's information is requested and uploaded; a care coordinator, usually someone who is empathetic and trained in hospitality, logistics and appointments; and a staff physician whose job is to be like a great primary care doctor. That doctor acts as a liaison with the specialist.

Traditionally, when patients go to their appointments, they haul radiology images or records into doctor's offices. Doctor's precious time was lost searching through paper records. Now the records are handled electronically, and organized in chronological order -- reversed, indexed, searchable, summarized, and loaded in to the cloud.

On a philosophical and a practical level, the company addresses problems in the broken system of health care delivery. "Health care is still based on how we did it in 1930, going to a family practitioner and writing down what is wrong and filing it in a cabinet. But with advanced imaging and the transporting of information across the globe, what we are doing is having doctors log on and look," Tripp said, adding that the specialists can often diagnose a patient immediately. This is priceless.

Obviously, investors think so too, investing a total of $106 million to date from Greylock Partners, Venrock and others.

"If someone can crack the code on the best physicians, that is a big deal. Navigating health care should not be this scary, and people need a coach that helps you through," Tripp said, adding that everybody should be an insider. "If you can navigate the same way that a Stanford doctor can, we have changed health care for the better," he said.