I have a recurring dream wherein I am staring into a mirror and shouting at myself.

I have run the gamut of pregnancy experiences: children, miscarriage and abortion. Having children and miscarriages and saying "those things were really hard" is completely acceptable. They are hard. Childbirth is hard, parenting is hard, losing a baby is hard -- they are physically and emotionally devastating in their various ways.

On the other hand, it seems we are allowed to speak about abortions in one of two ways: our insurmountable regret, or our complete lack of doubt.

I have spent the past six years tormenting myself for being in this in-between place of, "I'm sad about my abortion. I don't think I was powerful and in control. But I don't regret it either."

I had my children young. I am like newly mulched earth and could get pregnant alone in a field. I already want to justify this to you, to tell you that we were using birth control. This is me: I'm a woman who has been pregnant by accident four times, one time after using a condom and taking the morning after pill when I realized I was about to ovulate. But it doesn't matter. I know that about myself.

I should have been more careful -- more and more and more layers of careful.

When I found out I was pregnant with my first daughter, I was 19 and living with a guy I had known for three months. I had been working in a new job for six weeks.

That would have been the time to have an abortion, right?

I could have gone down the road and had a little sleep and it would have been over. I didn't -- and I'm glad, of course, because I love my daughter (now 11) very much, obviously -- but there begins my compounded and fraught relationship with my reproductive system.

I was so angry with it, for a while. I went through puberty when I was 10. No one had explained to me yet what a period was, but I had a little pack from DOLLY magazine with a pad and a tampon and a brochure.

I kept hoping it would go away. I peeked into my undies at recess and lunch and cried when the smear of blood had grown. None of the other girls in my class had theirs yet. We went on school camp and they went through my toiletries bag and teased me about bringing pads with me. I didn't understand my body and I was so mad with it.

I told my boyfriend, who was 20 at the time, that I was pregnant, and he didn't speak to me for three days. We hung in the house like old coats, silent and loose. I had been a person in the world, and now I was two people in the world.

I went to the doctor and he said, "Do you want a referral to a clinic?"

I told my mother and she said, "Are you going to fix it?"

It didn't occur to me for one minute to have an abortion, then, when I was 19 and barely knew my co-conspirator.

Sometimes I look at the photos of me in the hospital with my newborn daughter. She is perfect. She has a little round head and tiny fists and she is frowning and pursing her lips. And I'm there, in green sheep pyjamas, holding this porcelain doll, and I am a child. A confused, tired, child.

I have had children my whole adult life. I'm 32 years old now and I have never been able to just try to figure out what I'm doing without considering another person. I've been a mother since before I knew how to be a human.

So, because I am terrible, I repeated all my same mistakes. I had known my new boyfriend for three months, and I had been in my new job for six weeks.

And then, I was pregnant.

I have irregular cycles and I ovulated early, which is not an excuse but we were using condoms and it should have been fine.

It should have been fine.

It doesn't even matter that it should have been fine, because it wasn't, but it should have been.

I looked at the children I already had but still didn't understand. They were still so new, and I was still so new, and the collection of cells I had been harvesting were so, so new and I just couldn't keep compounding the newness of everything before I had managed to figure out how to do any of it. I couldn't perpetuate the cycle I had somehow broken into. And I absolutely couldn't rationalize trying to love another child before I'd figured out how to love the ones I already had.

So I had an abortion.

It was horrible. Not because there were picketers -- there weren't. Or because it was painful -- it wasn't. But because I was just so sad. It was an obvious decision and also not at all obvious. I would have wanted to love my child as much as I had ever loved anyone, but I wasn't sure I would have been able to.

I had no money, no family support and was effectively squatting in my marital home because I couldn't afford to leave. Everything was terrible. Having an abortion became part of the mix of terrible. When I think about that time, I can't feel my body.

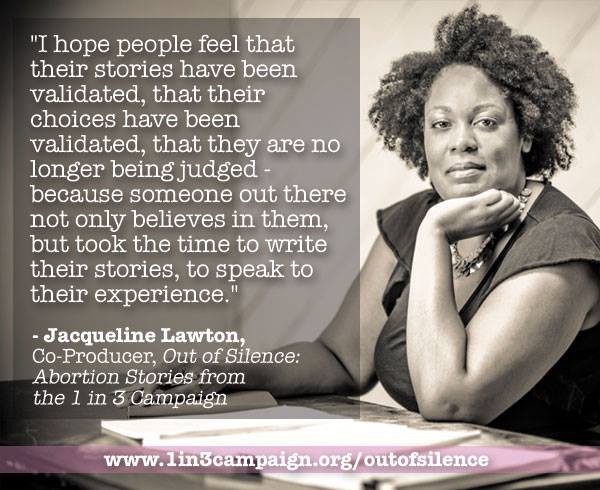

I read a quote this morning in a piece about Nicki Minaj's abortion:

I don't feel these things. I don't feel like I can't write about my experience, or that I need to write about it in order to validate my experience. My experience was valid. The people who care about me are supportive of the decisions I made. They were the right decisions. Those people believe in me.

No one who loves me is critical of the decisions I made then. They don't say to me, "Anna, I still can't believe you did that to your unborn child." They don't say, "Wow, you made some really bad decisions." The only person who does that is me. The only person who stands in front of a mirror and screams into it is me.

The person who needs to forgive me is me.

There is a grief process associated with abortion. For most people, there is a period of sadness and relief together. For some, there is just relief. For others, there is regret, or remorse. Sometimes it's short, and sometimes it isn't.

At the beginning of my book there's a dedication. It's not to my partner, or my kids, or my parents, or myself. It's the only way I know how to forgive myself -- to create something permanent (or with at least one print run) that gives some meaning to the experience I had, without dismissing it or dismissing my perpetually correct decision. It says:

For the person I knew infinitely,

and momentarily.

A version of this post originally appeared on Medium.