Threats to the world's children come in many forms.

I am one of the 80 million people who have watched the Kony video, and I will confess to being absolutely riveted by it, although not for the reasons you might think. Yes, I was moved and incensed by the atrocities inflicted by Joseph Kony on a generation of Ugandan youth. His abduction of an estimated 26,000 children -- many under the age of 15 -- and their forced conscription into armed guerrilla units sank the definition of child abuse to new lows.

That the video capturing this tragedy exploded on the Internet is understandable. Raw emotions -- the palpable fear and helplessness of Ugandan families seeking to escape the grip of Kony's army -- elevate the viral nature of the web.

Even so, it is worth asking -- what is it about this particular video that has hit a nerve with so many people, so much so that tens of millions have posted it on their Facebook pages, tweeted about it or forwarded YouTube links to others?

After all, the Kony video is not particularly timely. When the Ugandan civil war ended in 2006, Kony fled the country, reportedly to the Democratic Republic of Congo, thus eliminating any current threat to Ugandan children (although the same cannot be said for the youth of the DRC). Why the sudden interest in capturing Kony six years after he has left Uganda?

What's more, why focus solely on Kony? His actions, horrific as they were, were not unique. Just a few weeks ago, the International Criminal Court convicted Thomas Lubanga, a Congolese warlord, of the crimes of conscripting children under the age of 15 and turning them into killers. Large numbers of teenaged boys have reportedly been recruited for tribal fighting in Yemen, while in Myanmar as many as 70,000 children, some as young as 11, have been forced to serve in the national army. In Zimbabwe, the youth militia includes children as young as 10. Five years ago, Human Rights Watch estimated that there were as many as 300,000 children in 20 countries who were serving as soldiers for either rebel groups or government forces.

And what is it about forced conscription that has hit such a nerve? Not to minimize the atrocious nature of these abductions, but children in developing countries regularly face a myriad of untold hardships, including the lack of the basic necessities of life. Of the 1.9 billion children living in developing countries, 640 million live without adequate shelter. One in five does not have access to safe drinking water, leading to 1.4 million deaths a year. Some 270 million children have no access to healthcare, which helps account for the 11 million children who die each year from preventable diseases.

In every category, the numbers are staggering and lamentable, and yet, these very real threats to children's survival have not captured the attention and empathy of tens of millions of people the way that the Kony video has been able to.

Why is that? It's a question that I have been grappling with.

What I have concluded is not profound, although it may be instructive. I believe that the success of the Kony video stems from its ability to plainly, simply and unambiguously articulate both the problem and an actionable solution. Kony is personified as the singular menace, the lone enemy that must be stopped in order to put an end to childhood conscriptions in Uganda. In a poignant moment in the video, even the filmmaker's young son fingers Kony as the source of evil.

Having so clearly identified the problem, the road to a solution becomes equally evident: publicize Kony and his crimes in a way that leads to international notoriety and outrage. Then leverage this outrage to pressure elected leaders into taking action to find and capture him. There is a logical, sequential progression to it all -- apprehend Kony and the problem goes away... or at least part of it.

We know, of course, that the conscription of young children is a much bigger problem, but by narrowing the focus on Kony, by defining success so singularly, it gives people a greater sense that the issue can be resolved. And that hope feeds on itself in a way that becomes infectious.

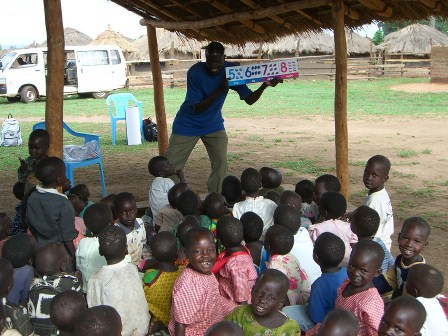

In the wake of the Kony atrocities, ChildFund worked in Uganda to help children and their families heal emotionally and return to a state of normalcy. After Kony fled Uganda, we provided child protection and psychosocial support to thousands of Ugandan children who were living in large camps of internally displaced people. In the years to follow, ChildFund Uganda worked to reintegrate the children who been abducted with their families, giving them a sense of safety and helping them overcome the emotional trauma they had endured. Even the children who were not abducted but who were afraid to sleep in their own homes in the rural districts of northern and eastern Uganda received help in getting past the fear that had gripped them for so long.

A ChildFund partner works with children in Uganda.

Beyond the Kony video, the many, many challenges facing the world's poorest and most vulnerable children cannot be reduced to a common denominator. There is no simple solution for improving children's access to clean water, adequate shelter and professional health care. These are long-term problems that require sustained and intricate solutions over time, applied at the community level. While it would be wonderful to produce videos that lit a fire of compassion over fixing the many hardships that children face, the reality is that the complexity of these problems cannot be reduced so simply.

It is heartening to know that so many people throughout the world have been inspired to act. But it is worth remembering that millions of children whose lives are threatened by other perils are worth fighting for, too.