Coraline (2002)

Coraline (2012; UK)

Classic books get to celebrate significant birthdays with shiny new editions these days: Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange, 50th Anniversary Edition; Margaret Mitchell's Gone With The Wind, 75th Anniversary Edition. Neil Gaiman's Coraline has only recently turned ten, but his 2002 novel is his most popular -- along with American Gods and Neverwhere -- and surely his most beloved. A generation of children has now grown up with, and cherishes, this story of an intrepid, likeable little girl named Coraline Jones, at the end of her summer school holidays in East Sussex, not so long ago. Its author cherishes the book, too. Says Gaiman: "It's the strangest book I've written, it took the longest time to write, and it's the book I'm proudest of." Coraline is a coming-of-age horror story and, 10 years after its publication, Gaiman reflected, "I've started running into women who tell me that Coraline got them through hard times in their lives. That when they were scared they thought of Coraline, and they did the right thing anyway."

What it is about Coraline that agitates, and captivates? The novel presents parallel worlds accessed by mysterious passageways and mirrors that are akin to Lewis Carroll's adventures under ground and through the looking glass. The connections to Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre are also powerful, though far less noted by critics. Jane is the first exceptional girl heroine of Victorian fiction; she is approximately Coraline's age when her story begins; she lives for most of the novel in a house with a terrifying parallel world in the attic; she is as intrepid as Coraline, and as alone much of the time. Gaiman knows what readers like, and have liked for centuries: he happily supplies, in this story designed for his own daughters, echoes of and allusions to fairy-tale and fictional heroines familiar to readers in English. In Coraline, he has his finger on the pulse of what you loved when you were little, what mattered to you. Gently, he warps it, and makes you afraid as you would have been then -- and perhaps even more so, now.

Gaiman began writing the novel when his daughter Holly was five, because she liked scary stories, and he picked it up again six years later to finish it for her little sister Maddy. As he said in a 2009 interview, "[Holly] used to come home from kindergarten, climb onto my lap and dictate these sort of terrifying horror stories about little girls whose mothers were impersonated by evil witches and would imprison them and then the little girls would have to get free and rescue their mothers." This, in a nutshell, is the plot of Coraline.

Neil Gaiman and his daughters Maddy and Holly, 2008, ©Neil Gaiman/Neil Gaiman's Journal

The heroine's name came from a typo in "Caroline." According to Gaiman, "I had typed the name Caroline, and it came out wrong. I looked at the word Coraline, and knew it was someone's name. I wanted to know what happened to her." That the name implies someone with heart doesn't hurt, for both her bravery and kindness are leading characteristics of young Miss Jones.

The Jones family -- Coraline, her mother, and her father -- have recently moved into a "very old house" at the end of a rainy, cool, misty Sussex summer." It's divided into apartments, and they share the house with "a crazy old man with a big moustache" who is training a mouse circus, and two former actresses, Misses Spink and Forcible, and their Highland terriers with "names like Hamish and Andrew and Jock." There is also a "haughty black cat" who seems to belong to no one, as cats do, but watches Coraline constantly. The "names like" is a hallmark of this book: most of the important characters Coraline meets have no names, like "the other mother" and "the cat," or, like "the voices," have lost them in the passage of time. As the cat says, in its perfectly superior cattitude, "you people have names. That's because you don't know who you are. We know who we are, so we don't need names."

School begins soon; so Coraline, a girl who describes herself as an explorer, has only got a week or so left to make one last adventure happen. As the house has an attic, a cellar, a huge overgrown garden, an abandoned well, and secret locked door, she is in just the right place.

When she's left alone, Coraline heads into the "ghost-world" behind that locked door, armed only with a hol(e)y stone, the gift of the old ladies downstairs, for protection. "She knew she was doing something wrong," but she does it all the same. When Coraline opens that door, a dark hallway does the opposite of beckons. It's a mirror image of her own home -- but turned wrong, somehow inside out, and outside in. The face of the boy in the drawing-room painting now looks calculating and nasty, his eyes peculiar. Those peculiar eyes get us ready, though not entirely prepared, for the bright dark button eyes of the other mother and other father she encounters. Everyone's rag doll, once upon a time, had buttons for eyes. This should be a comforting and familiar thing, but, for modern children, it isn't. Gaiman does this so well, and nowhere better than in Coraline: he makes the comfortable writhe in discomfort, the familiar forced into the frame of its opposite.

The white paper-skinned woman, tall and thin, with her long fingers, dark curved red nails, and those shiny black button eyes that terrify, is less like Coraline's real mother than like a paper cutout come to life. Other mother knows what Coraline wants, though. In this kitchen Coraline is immediately served a lovely home-cooked lunch of the sort her own mother never prepares, and that her father, with his yuppie recipes, fails to get right. Every child has an other mother, perhaps, in mind during her or his life -- a mother who wouldn't feed you fish fingers, or tell you to go bother the neighbors instead of her, but fills you with roast chicken, spares you the washing up, and encourages you to play with rats.

From Persephone's pomegranate to Alice's mushroom to Goblin Market to Edmund's Turkish Delight in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, there's always a penalty to be paid when anyone in a tale or myth eats food served by a suspect character. Coraline's made of stronger stuff, though. She doesn't eat out of greed, or curiosity, but out of hunger. Perhaps this is why she's not tainted, or transformed, by the food.

Coraline's other bedroom is entirely magical, a vivid, preppy pink and green -- not a place to sleep, perhaps because one is already in a dream? -- but full of interesting things. The books have living pictures, there are chattering tiny dinosaur skulls, and an adorable tank with a conscience and sense of embarrassment. The black rats sing her dream-song from home that she can't remember, until the other old man comes for them, "something hungry" in his eyes. The appetites in through-the-doorland are weird and immense. Everyone wants to consume Coraline, in one way or another. The cat (who can talk in this parallel world, and reminds me a lot of the dandy cat with his pistol and penchant for pyromania in Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita) understands: other mother "wants something to love," and she "might want something to eat as well." The two are not too subtly, scarily, related.

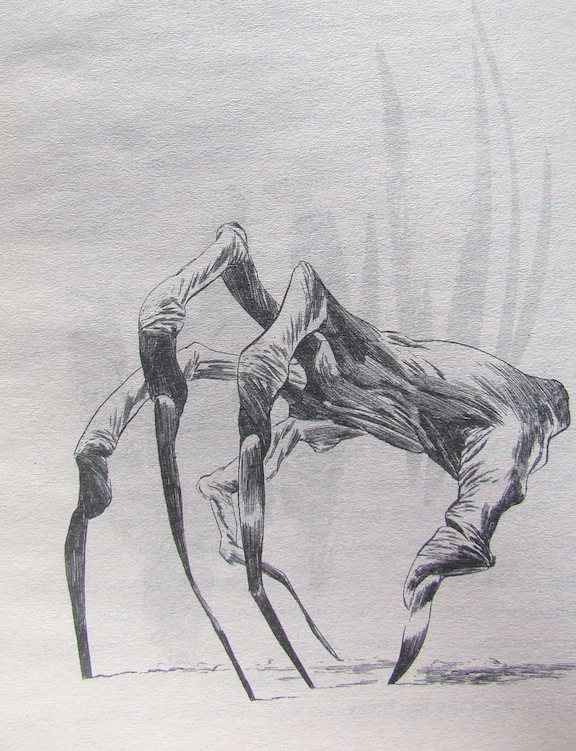

When other mother and other father ask her to join them as their real daughter, by having large black button eyes sewn into her own with a long silver needle, Coraline takes its first truly macabre turn. "It won't hurt," Coraline's other parents insist, but she refuses. As other mother reaches for her, Coraline's fingers close "around the stone with the hole in it. Her other mother's hand scuttled off Coraline's shoulder like a frightened spider." When Gaiman first showed a draft portion of the novel to his editor in 1991, he was told it was too frightening to children to be publishable. This scene was surely the beginning of why.

Trapped in the other world, the key taken by a rat, her real parents now confined in a snow-globe on the mantel, with three little spirit-children for company (but whose savior she must also be), Coraline steadfastly refuses to be overwhelmed. We root for her, hard. We don't want this brave little girl to have buttons sewn into her head, her strong humanity taken away for ever.

Like most witches, other mother can't resist a game, because she is confident she can only win. Coraline offers her self and soul for the others -- all of them, her parents and the dead children whose spirits other mother has nearly forgotten, but can still use against the living child she wants to take. Other mother agrees, and swears she'll keep her word on own her mother's grave -- into which she's put her: "And when I found her trying to crawl out, I put her back." This certainly isn't good enough for Coraline, so other mother also swears on her own right hand. In old England, amputation of the right hand -- later branding on the hand -- was a traditional punishment for writing treason, or for theft. With the help of the stone, Coraline finds two of the lost souls, hidden in marbles. As she succeeds, other mother's world begins to fall apart. The house begins to crumble; the lines of the trees and garden outside become dimmer, foggier, less and less there. Coraline confesses to knowing other mother loves her -- how can you define love, anyway? She is learning. She also knows that other mother is actively tricking her, but she has no other options but to go along.

Then Coraline finds a trap door. Nothing good is ever below a trap door, with its logical name. A trap, a grave, a no-exit: that's all it can be. What's left of the other father is here, and he -- or it -- can't fight against other mother's insistence that it hurt Coraline. He's tried, and been punished here until his gender, and any humanity he had, is gone. Coraline rips off its remaining button eye, but the giant worm-beast can still scent her, and in one of the scariest scenes of the book it slithers surprisingly fast after her to the steps as she runs and "began to flow up them." A creature like this shouldn't be able to navigate steps, and it stuns Coraline, and you, that it can. It's like a Dalek suddenly being able to levitate up a staircase and get you, when you were serenely sure it couldn't. Coraline barely escapes, and locks the door. Where there are keys, there's a lock for that key. Use them for your protection to keep bad things locked out, and at your peril to see what's behind a locked door -- likely locked for good reason.

Upstairs in the rat-flat, with the help of the cat, Coraline finally finds the third marble, and now understands where her parents are. Face to face with other mother, in the shambles left of the drawing-room, Coraline tries not to look at, not to even think of, the snow-globe and the two little figures trapped inside. Once she has it in her hands, in a scene straight out of Edgar Allan Poe and "The Black Cat," the cat slashes at other mother's head as Coraline begins to run. She won't abandon her ally, and sees to it the cat is safe too. The three help them both escape: "ghost hands lent her strength that she no longer possessed." Something falls from head height, and Coraline runs, touching the passageway's walls, walls that are sides and insides, living. In their real home, an exhausted little girl and an exhausted cat fall asleep on a beautiful summer's day.

Is it over? No. Other mother's game with Coraline has been a game of wits, and must be resolved in the mind, not in a flurry of action with flung cats and slammed doors. Coraline must outsmart what fell from head-height as the heavy door slammed shut, the sound and shadowy sight Coraline has thought she sees in corners, under furniture, following her: other mother's scuttling white hand, with its claw fingertips, seeking the black key so it can reunite with its body.

What would you do in Coraline's situation? I might've melted the key down immediately, or flung it far into the sea and replaced it with a cunning replica. The vicious right hand, though, is smart enough to be able to tell the difference. You'll need to read the book to find out what happens in the end....

the other mother's hand, illustration by Dave McKean

Coraline has been made into a graphic novel (2008), an off-Broadway musical (2009), and a stop-action, 3D animated movie, nominated for Best Animated Feature at the Academy Awards, in 2009. Black Phoenix Alchemy Perfumes have a whole Coraline line. In an audience of Gaiman's in 2010, a child named Caroline "wore a pair of oversized buttons, strung on clear fishing line, over her eyes," and a four-year-old brought him a photograph of herself dressed as Coraline for Halloween. The popularity and power of the book contain media multitudes, but the text itself is what drives all else.

Now let Gaiman, and his friends, read Coraline to you. It's a necessary thing to have stories read aloud.

quotations from the author and book are from Neil Gaiman, Coraline, 10th Anniversary Edition (HarperCollins, 2012)

©Anne Margaret Daniel for Huffington Post Books

Please read my full review of Coraline (spoiler alert!) in The Literary Encyclopedia