JERUSALEM -- Before the war, Erich Lederer was a charming Vienna ladies man, a pillar of bohemian society who angled to meet Josephine Baker as Austrian church leaders were deeming her unfit for polite company--and told his family they had an unforgettable romance.

JERUSALEM -- Before the war, Erich Lederer was a charming Vienna ladies man, a pillar of bohemian society who angled to meet Josephine Baker as Austrian church leaders were deeming her unfit for polite company--and told his family they had an unforgettable romance.

He grew up in a cultural hothouse. His intellectual Jewish mother, sister and grandmother were subjects of Gustav Klimt portraits, and Lederer was portrayed by a Klimt protege, Egon Schiele.

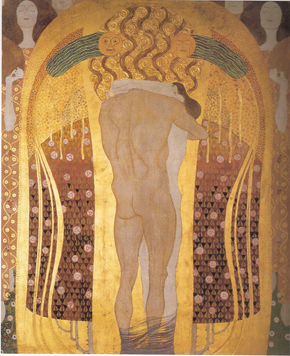

After a love life that older Viennese still talk about, Lederer settled down with a beautiful aristocrat. His pride was his art collection, in particular Klimt's epic, experimental "Beethoven Frieze," a series of frescoes 112 feet long that depict an existential struggle for happiness in which the forces of darkness are defeated by love and justice.

Lederer's charmed world ended when Adolf Hitler marched into Vienna in 1938. The fall of the Lederer family was swift: their property was seized, along with a vast modern art collection of Klimt's most experimental works, including the Beethoven Frieze.

Lederer survived World War II in exile, and he spent decades wrangling with Austrian officials for the right to take the Frieze to his post-war home in Switzerland. He gave up in disgust in 1973 and accepted $750,000 for the Frieze--though its assessed value was around $2 million.

Now his heirs want the Frieze back.

Austrian officials, who have been forced to return a dozen stolen Klimt masterpieces since the 1990s, say they will study the claim.

Getting the Beethoven Frieze out of Austria became something of a mission for Lederer. The war had transformed the onetime bon vivante into an angry man who was haunted by the betrayals that had crushed his world.

Some of them were deeply personal: One of his aristocratic friends had married his sister, Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt, but when Hitler arrived he announced himself a Nazi and "Aryanised" her property, leaving her to die alone in a dark apartment. Erich's widowed mother fled to a Budapest sanatorium and died before deportations began.

The Beethoven Frieze had been exhibited in 1943 at the largest show of Klimt's work ever, sponsored by Baldur von Schirach, the Nazi governor of Vienna.

After the exhibit, the Lederer collection was sent to Immendorf Castle for safekeeping by the Gestapo. Retreating SS officers burned the castle after the Nazi defeat, and as many as 18 Klimt may have burned. Several of them, like Klimt's experimental masterpieces, "Medicine," that the Lederers helped the Belvedere museum acquire, were never photographed in color.

After the war, Lederer was crushed. The Klimt paintings represented the golden moment his family had lived in Vienna, and he focused his wounded psyche on trying to find them. His mother and sister's looted Klimt portraits were recovered just before they were to be auctioned off, but the Klimt painting of his grandmother, Charlotte Pulitzer--a Hungarian cousin of American newspaperman Joseph Pulitzer--was never found.

Searching depots of looted art, Lederer found the fragile Frieze panels languishing alongside puddles in a monastery with gaping holes in its roof from allied bombings. He asked for an exit permit to take the Frieze to his new home in Switzerland, where he wanted to mount it in a public building.

But Austrian officials refused to give Lederer an export permit, even when he offered to "donate" the rest of his art collection in exchange for it. Officials moved the panels to a former stable at the Belvedere Palace, where they charged Lederer rent to store it for years--because technically, it was still his property, they told him.

Lederer had no place to house the four-ton Frieze in Austria: The Nazi state had confiscated the Lederer great house, a historic mansion where Klimt and other artists socialized, and officials held onto it after the war until it finally caved in from neglect in the 1960s.

Austrian officials did give Lederer export permits for other paintings in exchange for "donations" of some of his art seized during the war--a quid pro quo extortion method used to give Nazi loot a post-war legal veneer.

Finally, in 1973, Erich, an old man with no hope of getting the deteriorating Frieze out of Austria, gave up, and sold it to Austria.

The challenge by his heirs is based on a 2009 change to Austria's art restitution law to covers cases in which the disputed art is sold for less than its value.

It would be a blow for Austria to lose the Beethoven Frieze, which is elegantly displayed in the Vienna Secession building, an avant garde art palace funded by Jewish patrons, including the father of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, that opened in 1898.

The Secession was where the Frieze was first exhibited in 1902, at an opening where Gustav Mahler conducted a movement from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony that was the inspiration for Klimt's visual "Kiss to the Whole World," though to many critics the Frieze was "Pornografie."

For decades later, the Secession was the home of the 1943 Nazi era Klimt exhibition, sponsored by Vienna Nazi governor Baldur von Schirach, that is still the biggest Klimt show ever. As I reported in "The Lady in Gold, the Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt's Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, it was necessary to change the names of the portraits of "Klimt's Women" to hide their Jewish identities.

The Secession building burned down in 1945 when German soldiers decided to torch tires stored there in advance of the arrival of the Red Army. It was reconstructed after the war.

Austrian officials consider the Beethoven Frieze a patrimonial piece of art.

But like many Klimt works, it was collected by families of the Jewish intelligentsia who were run out of Vienna, while their paintings became Nazi loot and wound up in Austrian museums.

Austrian museums have been forced to give up a dozen stolen Klimts since Vienna emigre Maria Altmann and Los Angeles attorney Randol Schoenberg began their successful struggle in 1998 to reclaim the Bloch-Bauer family Klimt collection from Austria, including the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer that sold for $135 million to the Neue Galerie in 2006.

The latest dispute involves a claim to the Klimt portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl

that is hanging at the National Gallery in London as part of its exhibit, "Facing the Modern, The Portrait in Vienna in 1900."

The ongoing Klimt saga is likely to get further scrutiny in the wake of the upcoming George Clooney film, Monuments Men, that dramatizes the Nazi art thefts.