Two very different Israeli documentaries are opening at New York's Quad Cinema over the next 10 days. These fascinating films have less to do with the political tensions that dominate headlines from the Middle East than with exploring personal identity. Dolphin Boy (April 27) is about an Arab teenager who was traumatized into muteness after a savage beating by classmates, and finally responded to the unconventional therapy of swimming with dolphins. Chronicling a Crisis (May 4) is a disturbing but riveting portrait of filmmaker Amos Kollek, including his difficult relationship to father Teddy Kollek (the celebrated Mayor of Jerusalem for 28 years). Both tales of blockage take place in the mid-2000 era and center on a father-son relationship -- one Arab and nurturing, the other Jewish and enervating.

Credit: Dani Menkin and Yonatan Nir

Credit: Dani Menkin and Yonatan Nir

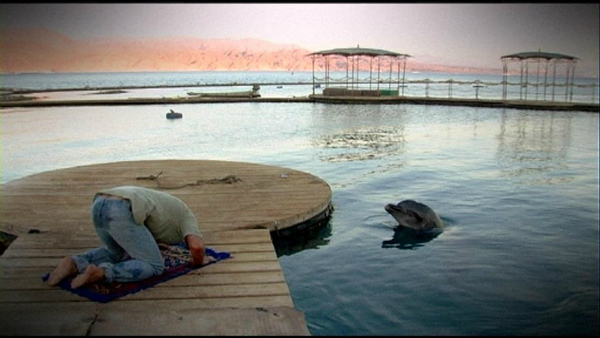

Directed by Dani Menkin and Yonatan Nir, Dolphin Boy unfolds like a video diary, spanning four years in the life of Morad Azba: his innocent text message to a female classmate in an Arab village results in a brutal attack by her brother and friends. Almost catatonic, he is treated by a psychiatrist, Dr. Ilan Kutz, who recommends dolphin therapy in Eilat's Dolphin Reef after traditional methods fail. The relationship of the Arab teen and the Jewish doctor transcends ethnic tension. And it is Morad's father Asad who emerges as a truly heroic figure in his devotion to his child: his voice-over says that -- above revenge and anger -- his priority was to save his son.

Credit: Dani Menkin and Yonatan Nir

Credit: Dani Menkin and Yonatan Nir

As in Precious Life, Shlomi Eldar's inspirational documentary presented on HBO in 2011, we see a Jewish doctor deeply engaged in saving an Arab child. Whereas Precious Life focused on an Israeli pediatrician and a Palestinian woman whose baby has an incurable genetic disease, Dolphin Boy traces the efforts of a father who chooses to sell his precious ranch in Northern Israel in order to stay close to Morad.

Credit: Dani Menkin and Yonatan Nir

Credit: Dani Menkin and Yonatan Nir

During a post-screening of Dolphin Boy at Manhattan's Jewish Community Center in November, Dr. Kutz provided an uplifting update: not only is Morad functioning well, but someone who saw the film gave Morad a scholarship to study hydrotherapy. Yonatan Nir concluded with a superb political point: the dolphins never knew if someone swimming with them was Arab or Jewish.

Nir's assessment of Dolphin Boy during the Q/A-- "how vulnerable we are, and how resilient we are" -- might be applicable to Chronicling a Crisis. Amos Kollek is not, strictly speaking, an Israeli filmmaker, having directed numerous English-language independent features in New York. And his focus has been less political than feminist, exploring the lives of edgy women played by an international array including Hanna Schygulla (Forever Lulu), Anna Thomson (Sue), and Audrey Tautou (Happy End). Chronicling a Crisis moves between Jerusalem, where his father is dying, and New York's East Village, which provides the filmmaker with a raw (and raw material) heroine in Robin.

Credit: Osnat Shalev Kollek

Credit: Osnat Shalev Kollek

Kollek meets Robin Remias at a pay phone, where she is responsive to his live camera. A hooker with a drug habit, she seems like an antidote to Kollek's torpor, lack of confidence, and creative block at age 56: "I'm like a director but I have no sense of direction," he says. His film follows two main strands -- the smart, self-revealing and self-destructive Robin, who he believes could act in his film, and his wheelchair-bound father. The common thread seems to be his wish to save them; in fact, he toys with the title "Chronicle of a Suicide," wondering who will die first -- his father, Robin of drugs, or himself.

Credit: Osnat Shalev Kollek

Credit: Osnat Shalev Kollek

Kollek admitted in an interview that the years 2004 - 2010 were "a crazy time in my life, when I felt unable to work or to find myself." But he recorded this limbo with his mini DV camera: "I went with my instincts -- no censorship -- documenting the people that shaped my life." The result is alternately painful and poignant, containing a sharp authenticity of detail, like the fed-up look of Kollek's wife Osnat, or the way Robin spoons ice cream and cake into her mouth, or the ambivalence still palpable when Kollek is with his diminished father. Chronicling a Crisis is an extremely unflattering -- but revealing -- self-portrait.

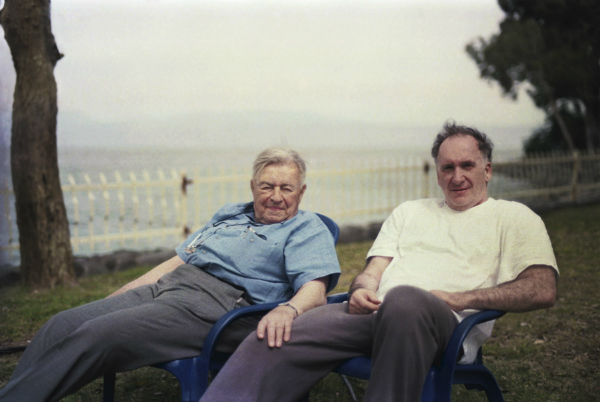

As in Dolphin Boy, a father's presence is constantly palpable. Although it is sad to see the once-robust Teddy Kollek so frail, a lovely moment transpires when he smiles at the sun near the Sea of Galilee. One wants to believe that he is smiling at the son as well, illuminating an internal landscape.

Unlike fiction films, documentaries often have no screenplay. The filming is a process of discovery, whose conclusion remains unknown -- and unknowable -- until the shooting is over. After years of filming, both Dolphin Boy and Chronicling a Crisis endow their subjects with a voice.