Over the past several years mass incarceration has become one of the most debated criminal justice issues in American media. As we have realized the error in the model of incarceration used over the last 30 years in the United States, a movement to decrease the number of people imprisoned has gained momentum. Despite this, the reality of the systems truly unfair application, and the resulting fallout has not been fully discussed.

American incarceration is not a problem with consequences that have been levied evenly across gender, and racial lines. Even though they are only 6 percent of the U.S. population a mere 19 million people counting children, African American males make up nearly half of all American prisoners (with a total of around 800,000 people imprisoned). This represents a 500 percent increase in the number of black men behind bars since 1980.

The incarceration rate for young black men ages 20 to 39, is nearly 10,000 per 100,000. To give context, during the racial discrimination of apartheid in South Africa, the prison rate for black male South Africans, rose to 851 per 100,000.

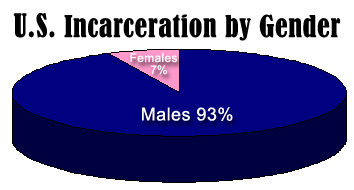

As shown in the chart above, the incarceration rates for black males are in contrast to much lower numbers for other groups. Despite the images portrayed by shows like Orange is the New Black, nationally there are a relatively small number of women of all races behind bars. 93 percent of the total number of Americans incarcerated are men, and only 7 percent are women. Of the over 2 million Americans incarcerated, only 200,000 are women.

In the piece, "Men Sentenced To Longer Prison Terms Than Women For Same Crimes", the role gender plays in sentencing after conviction is reviewed.

Sonja Starr, an assistant law professor at the University of Michigan, found that men are given much higher sentences than women convicted of the same crimes in federal court. The study found that men receive sentences that are 63 percent higher, on average, than their female counterparts.

Compounding the above discrepancy in incarceration between genders, is a gap in punishment between black and white men. Black men often get longer sentences than white men for the same crime. The Wall Street Journal article, "Racial Gap in Men's Sentencing" states,"... sentences of black males were 19.5 percent longer than those for whites."

These disparities aren't explained by genetic, or social variation between the genders and races. The differences are the result of systemic bias in arrest, convictions, and sentencing. African American men are largely incarcerated for poverty crimes such as low-level drug offenses, failure to make child support payments and driving without a license. As stated by Columbia University Professor of Education and African American Studies, Marc Lamont Hill in the MSNBC video segment above.

We want be careful not to suggest mass incarceration is due to some kind of cultural poverty, as if poor people or black people are more prone to go to prison. The fact is black people are targeted to go to prison more. If I went to Harvard University or Princeton University on a Friday night I could arrest a lot of people for simple possession of drugs, for public drunkenness, public urination or disorderly conduct. But, were not looking at Harvard or Princeton. We go to poorer neighborhoods like in New York where 3 counties produce 70 percent of the state's prisoners.

The immense gap in levying of punishment plays a major role in our social decision of who is prone to criminal behavior, even before an act is ever committed. It effects who gets stopped and frisked allowing an officer to find their common possession level drug crime, and who does not. Who is seen as integral to the home as a parent and given probation, and who is not. Who is seen as safe, and who is not. Effectively, who is seen as a valuable part of our society, and who is deemed expendable. Imprisonment inequity is one of the foundational pillars of the American mass incarceration model. In a growing sense, fairness for all seems more illusory than actual.

Part of the issue is our incarceration system is now burdened with quotas built into many private prison agreements with state governments. The piece, "Prison Quotas Push Lawmakers To Fill Beds" shows this:

Far from the exception, Arizona's contractually obligated promise to fill prison beds is a common provision in a majority of America's private prison contracts, according to a public records analysis released today by the advocacy group In the Public Interest. The group reviewed more than 60 contracts between private prison companies and state and local governments across the country, and found language mentioning quotas for prisoners in nearly two-thirds of those analyzed ... Private prison corporations emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, at a time when crime rates were soaring and states were scrambling to keep up with surging prison populations. Lawmakers needed quick alternatives, and looked to private prisons as an overflow valve to house inmates who were overcrowding the existing state systems.

But as state prison populations have started to decline in recent years, advocates point to occupancy guarantees as long-term obligations that raise core questions about who benefits from the service: the state, or the prison contractor?

The problem is as a society we don't commit enough crimes to service the prison population numbers that states agreed upon in these contracts. How did we get to the place we are at now? Where effectively, it has been deemed the lives of young black men are the sacrificial lamb to cover the shortfall in these contractual prison debts that are now due.

The consequence that results socially due to these types of discrepancies in imprisonment also effect arrest, convictions, and sentencing adding another dimension to the problem. For our jury based system to work a reasonable amount of parity in treatment is needed, no matter if you are a 34 year old college educated white mother in North Dakota found with illegal prescription drugs, or a 20 year old high school educated black father in Alabama caught with a small amount of marijuana. Our system relies on an objectivity, that requires a semblance of fairness. From jurors deciding whether a crime was committed beyond a reasonable doubt, to officers that apply standards of reasonable suspicion for a stop, or fear of imminent danger to justify the use of deadly force.

The New York Times piece "Key Factor in Police Shootings: 'Reasonable Fear'" explains:

Every step, however, is overshadowed by a single imperative: If an officer believes he or someone else is in imminent danger of grievous injury or death, he is allowed to shoot first, and ask questions later.

Mass incarceration has infected this process with bias that weighs far too heavy on our individual judgement of black males. As proven in Cincinnati where Samuel Dubose was gunned down by an officer during a routine traffic stop in possession of what has been found to be a bottle of air freshener, and in South Carolina where Walter Scott was shot in the back by a police officer under similar circumstance.

It is likely both officers will use fear of imminent danger as the reason for their respective uses of deadly force. Inequity in incarceration allows space for justification of fear or suspicion when detaining certain segments of our society, where there should have been none. Mass incarceration has created a constant state of an officer being able to assert to a grand jury there was the belief of imminent danger when there is interaction with a black man. While the required proof by the officer to justify actions would be higher when dealing with other groups. This is the result we are left with, whether it is in the case of Eric Garner's explanations to police officers falling on deaf ears, or 18-year-old Mike Brown who was described by 6' 4" Officer Darren Wilson as being like "Hulk Hogan". Through mass incarceration we have made young black males the prototype of a criminal suspect that induces fear, and the result has undermined much of our nation's model of due process.

If an officer has been trained in a society with this level of incarceration bias applied to specific groups over others, can he truly evaluate his fear appropriately to judge by the above vague standards? If a jury member is bombarded with this overly incarcerated view of black males as prisoners, can that citizen fairly evaluate a given case individually and truly judge the defendant beyond a reasonable doubt? The fallout of mass incarceration has been as detrimental as the institution, leaving a black cloud we all live under, but few acknowledge exist.

--

Antonio Moore is a former prosecutor in Los Angeles. He is also one of the producers of the documentary on the Iran Contra, Crack Cocaine Epidemic and the resulting issues of Mass Incarceration "Freeway: Crack in the System presented by Al Jazeera". Mr. Moore has contributed pieces to theGrio, Huffington Post and Eurweb on the topics of race, mass incarceration, and economics.