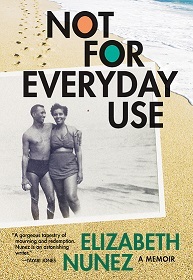

Ask any parent and they hasten to tell you about the vision or aspirations they harbor for their children. The method adopted for realizing the dream varies from household to household. And oftentimes, it takes the death of one or both parents for the child, by then an adult, to appreciate in hindsight the wisdom of the parents' ways. Such is the journey author Dr. Elizabeth Nunez undertakes in her memoir, Not for Everyday Use.

Upon learning of her mother's death, Nunez packs her bags and sets off from her adopted homeland in America bound for Trinidad, the country of her birth. Gathered at the ancestral home, the siblings make preparations for their mother's burial and tasks are delegated according to profession. "The ones with business acumen will discuss finances with the funeral director; the ones with medical backgrounds will gather details from the hospital about my mother's last hours; the more religious of us will speak to the parish priest to arrange a suitable Mass ... the ones who understand Caribbean protocol and style, will be in charge of the flowers, the program at the church and at the cemetery, the meal that will follow the internment, the guests to be invited to our parents' home." Given her calling or vocation as a professor, Nunez is entrusted with writing the eulogy.

Nunez reflects on her mother's legacy as she works through her grief, and demonstrates mastery of her craft, shifting from present to past, weaving together vignettes, sprinkling her prose with bits of poetry, to provide the reader with a fascinating backstory. "I write and write, the good amanuensis, taking notes from my siblings but all the time battling a darkening fog gathering in my head ... Then, later, when I am alone, faced with the task of fashioning the notes into readable prose, the fog clears." Constantly measuring herself against her mother, and occasionally her siblings, Nunez second guesses decisions made and wonders about alternative outcomes.

Even in the midst of grief, restraint prevails. Nunez meets her sister at the airport, "We embrace. A kiss on the cheek, our arms enclosing each other in the second of that kiss. No tears. We are not a weepy family. We are Nunezes. We have been taught to keep our emotions in check. Emotions can be dangerous. They can derail you." But this very restraint is what kept Nunez from falling apart during her four years as an undergraduate student in the 1960s, without a support system in a foreign country hundreds of miles away from her parents.

The credo of the Nunez household, "Ambition is made of sterner stuff," was instilled in the children from a very young age. Nunez acknowledges, "My parents did what they thought best. They prepared us to succeed in the world they knew, a world where your country was not your own and belonged to people who did not look like you, who lived far across the ocean in a distant, cold land ... You had to be made of the sterner stuff. The colonizer succeeds when he manages to colonize your mind."

As the narrative shifts from the domestic household to the larger Trinidadian society with its stratification, Nunez provides us with a glimpse of the various dynamics at play. Nunez's father secures a managerial post at Shell Oil Company, before moving to the Ministry of Labor as a junior minister shortly after the country gained its independence from Great Britain. But he carries with him the psychological wounds from an incident that occurred when he was much younger, starting his first job in the civil service. One night as her father rode the bus home, he overheard the conversation of fellow passengers who were en route to a social gathering. Realizing that the gathering was being hosted by his relatives, her father was about to interject when one of the parties to the conversation pointed a finger at him saying, "What are you looking at, you silly boy. Mind your own business. Don't you have friends in your own backwater village?" Humiliated, he sat down, keenly aware that in spite of his attire, "it was his dark skin that told them I was not of their class, not fit to be in their company." Families are not immune. One of Nunez's uncles, shades lighter than the rest of the clan, changed his last name to Nunes and immigrated to Canada where he passed as white.

Nunez states that her first novel led her to the path of self-discovery to "untangle the threads that left her uncertain of her identity." Her memoir, then, is a journey of atonement and reconciliation.

Elizabeth Nunez will be reading from her memoir, Not For Everyday Use, at my annual Labor Day Literary Brunch.