"The heart of the uprising," "The symbol of a divided nation," "the neo-cons' worst nightmare"... These are just a few of several descriptions from over the last few weeks that have been used to frame Tahrir Square. Alongside the hundreds of media reporters and news correspondents, culture writers also jumped on the coverage bandwagon and began to ponder the role that the events would play in shaping the practices of Egypt's contemporary artists. With a self-proclaimed expertise on all things Egyptian that would make the likes of New York Times's Thomas Friedman seem humble, these cultural pundits sounded more like political analysts than art critics as they clashed and concurred on the state and fate of the arts in Egypt. The politicization of art from the Middle East was rampant enough already without a full-blown Egyptian revolution to fire the imaginations of these devotees of "radical chic" (as Tom Wolfe would call it), these ardent fans of "socially engaged art."

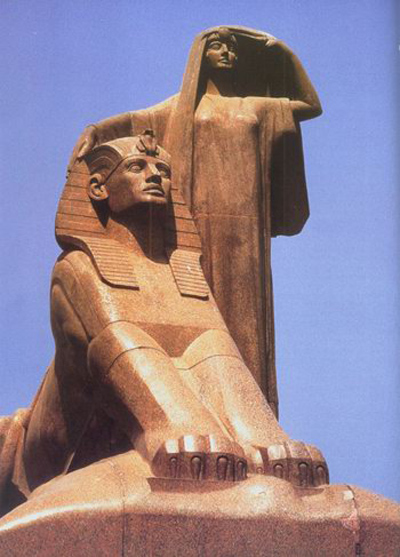

Mahmoud Mukhtar's "Egypt Awakening," 1928 / Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Here, I am guessing, are what could be the titles of some of the curatorial projects that will emerge over the next few years: "The Art of Revolution," "Beyond January 25," or how about something more psychedelic: "Art After Mu-Barack," to suggest the ties between the fallen dictator and Obama? Such initiatives will likely make some politically correct references, as slapdash as these might be, to some combination of Edward Said, Giogio Agamben, and Jeremy Deller's project "It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq." The subjugation of form and aesthetics to an agenda of political resistance will be as jarring as the surreal and shameful geographical misplacement of Egypt by Fox News, which infamously labeled Iraq as Egypt at the height of the uprising.

So how can one respond to the divinations that are circulating about the destiny of the arts in post-Revolution Egypt? I, for one, prefer to steer away from -- even caution against -- mixing art criticism with political fortunetelling. To understand the current conjuncture, I find myself compelled to explore a certain syncretism, one that combines urban topography with art history, and that takes us back in time, bringing us, once more, to Tahrir. The Square happens to lie exactly at the center of a six-kilometer diagonal axis that extends from Ramses Square -- the location of the city's biggest train station, built under the Khedive Ismail in 1856 -- and the Main Boulevard leading to the entrance to Cairo University. While the beginning and end points of this track seem to have nothing in common except being two of the sporadic crossroads of noise within the bustling Cairene metropolis, they share a common legacy that connects them to one of Egypt's most respected modernist artists: On May 20, 1928, Ramses Square was the spot at which the artist Mahmoud Mukhtar's seminal sculpture "Egypt Awakening" was unveiled. The sculpture now resides at the gate to Cairo University.

Since the 1919 revolution, and throughout the '20s, Egyptian national sentiment was on the rise. The Wafd party was at the peak of its popularity (its heyday would not wane for at least another decade due to the party's accession to the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936.) In 1920, the Wafd leader Saad Zaghloul met Mukhtar in Paris at the International Exhibition of Le Grand Palais where the latter had won a gold medal for a marble model of what would later become the legendary monument. Stirred by the tide of change that was sweeping across his motherland, Mukhtar decided to return to Egypt and dedicate his entire energy for the next eight years to the realization of a sculpture on a mammoth scale that would express the majesty of the people's resurrection.

It did not take long, however, before both artist and artwork got embroiled in a push and pull of political maneuverings between the Palace and the Street, the monarchy and the masses. King Fuad I had met with Mukhtar early on upon his return, asking the artist to execute a statue of himself. He probably envisioned in his person a more appropriate symbol for the rise of a new Egypt. The artist would not comply with the monarch's vanity. Mukhtar's humble origins had never left him. On May 20, 1928 -- the day of the inauguration -- the paper Al-Ahram featured a short biography of Mukhtar detailing his rags-to-riches story: A talented boy from Tambara, he had enrolled in 1908 at Prince Youssef Kamal's School of Fine Arts, and was sent to Paris on a scholarship to continue his training in the City of Lights. For the people, Mukhtar was a living embodiment of a social mobility that could only be attainable via the empowerment of the individual. For the Ancien Régime, he was still confined to the role of court artist who propagated the tastes of the Monarch. The execution of "Egypt Awakening" therefore represented a symbolic transition to a new era.

Sometime in April 1925, Hussein Sirri, the minister of public works, declared that there were no funds allocated for the completion of the statue, claiming that the government was not aware of such a project. Al-Ahram fired back, and on the April 18, 1925, exposed the underlying sabotage: "The will of an individual or a handful of individuals is seeking to undermine the will of the entire nation!"

It was indeed the will of the people that prevailed on May 20, 1928, when the sculpture made its debut, and Mukhtar's legacy was secured. But it took more than just an article or two for that to happen. In April 1928, the Wafdist opposition figure Mustafa El-Nahhas was elected as Prime Minister, albeit for a few months only. (He would be re-elected in 1930, between 1936 and 1937, from 1942 until 1944, and finally between 1950 and 1952.) El-Nahhas saw in the sculpture a timely opportunity to display his nationalist credentials. In tandem with a government that now drew its legitimacy from its alignment with popular sentiment, there was a patriotic national identity in formation -- in today's terminology it would probably be best described as non-sectarian, even "secular." This was evident in the writings of the intelligentsia of the time who constituted a significant locus of the opposition. In 1907, when the foreign press, for instance, was waging a campaign against the nation's Muslims, accusing them of religious fanaticism, Dawoud Barakat, a Lebanese Christian and the chief editor of Al-Ahram charged back: "The Franks [Europeans] just cannot get it into their heads that others are entitled to their own feelings. They think that it is only for Islam's sake that Morocco resisted the French, that Egypt and the Afghans resisted England, and that the Caucasus and Iran resisted the Russians." It was this same Barakt who, through the role he played vis-à-vis his senior position at Al-Ahram, expanded the public's awareness and rallied support for Mukhtar's sculpture.

Nevertheless, and despite all these favorable changes that were taking place, I cannot help but wonder how Mukhtar's work would have evolved if he hadn't allowed himself to be entangled in the political tug-of-war between the Palace vs. the Street, that is, if he had aligned himself more with the possibilities of the avant-garde and less with the confining search for a national identity. It is evident from various biographical sources that the burden of his mantle as national artist was an issue that plagued Muktar during his student years at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris even before his return to Egypt. I think of some of Mukhtar's contemporaries, of Brancusi and what he could have amounted to if his talents had been co-opted for the interwar România Mare, or of Boccioni had he favored an essentialist mythology of the Italian motherland instead of the futurism of Balla and Marinetti.... The cost an artist can pay for partaking in the construction of countrydom can be too dear a price, as Mukhtar's example reveals.

Mukhtar's artistic career overlapped with the last few decades of Egypt's monarchic period. Back then it was expected, almost inevitable, that artists would hold public servant positions in the cultural field. As a matter of fact, this was a trend that would continue through the 1952 Nasser Revolution -- and up until a few weeks ago. The more closely artists aligned their style and subject matter with the tastes and politics of the regime, the higher up they could reach within the echelons of institutionalized power. Mukhtar chose not to comply with this norm. While working on "Egypt Awakening," he was asked to register as a public servant in order to ensure the continuous flow of funds from the ministry of public works. In retaliation, he penned a shocking letter declining the offer. "I am asked to provide two letters of good conduct," he wrote. "Well, it happens that my conduct is bad. I have a bad temper. I was sentenced to 15 days in prison. Furthermore, I wear a beard and that is frowned on here. I am a bachelor, and I frequent certain particular houses. You see, I am therefore condemned to never become a public servant, ever. Please accept the expression of my distinguished regards."

Art Reoriented cultural director Sam Bardaouil

/ Courtesy Sam Bardaouil

Yet despite his anti-bourgeois disposition, Mukhtar soon settled into an equally perilous persona, starting to believe in the role that he was assigned as political symbol of Egypt's reawakening. In the 1949 publication "Moukhtar ou le réveil de l'Egypte" by Badr El-Din Abu Ghazi and Gabriel Boctor (published 15 years after Mukhtar's death at the age of 41), the artist is quoted as having said: "There had been no sculptor in my country for seventeen hundred years and the images that appeared among the ruins and sands at the edge of the desert were considered accursed, evil -- no one should go near." Do not underestimate the burden of being, or at least believing oneself to be, the first Egyptian sculptor in two thousand years. It is certainly too huge a job title for any single man to live up to. Pride comes before the fall, and official recognition ushers the kind of comfort zone that stifles the individualistic, non-conformist freedom of experimentation that leads to stylistic evolution. This is what ensues that when art marries politics, when creative expression is coerced into becoming a mouthpiece of social reform and an artist can become the minister of culture (as the Egyptian abstract painter Farouk Hosny from 1987 to 2011).

Back to the present. The similarities between the foment of Mukhtar's times and the first few weeks that followed the January 25 Revolution are remarkable. The desire for a new awakening, removed from the vanity of a monarch, was loudly resonating in the words and actions of protest that poured into Tahrir Square from every corner and led to the stepping down of the president. The Barakats of the social media world wrote their articles, changed their Facebook status and sent their Tweets rippling across the globe. They were determined to prevent their secular revolution from being "Islamicised" or hijacked by any dubious agenda, be it regional or western. And the artists? They were also there; some of them were injured, even killed in the fights that erupted between the pro-change demonstrations and their opponents. They, like the rest of the population, eat, drink, and breathe the politics of change sweeping throughout their land.

For decades, the work of many contemporary Egyptian artists has been subversive and politically opposed to state-sanctioned forms and topics of expression. But things are very different now. These artists have suddenly woken up to find themselves, and their art, no longer among the marginalized, but within the first ranks of the new order. The pressure on them to reflect on events that have altered their nation must be insurmountable. It is more likely than not that their work will be bullied into becoming a platform through which they would have to postulate the foundations for political amendment, enunciate the rhetoric of the uprising, and proselytize on the virtues of the revolution. Some of them will probably be asked to join the revamped ministry of culture, even to become ministers. This is where Mukhtar's cautionary tale becomes extremely relevant. The moral of the story: The fissures between Palace and Street are too wide, too steep for artists to bridge without risking the loss of their creative autonomy. Art will not evolve if it is obfuscated by being yoked to agendas of reform, even if they are as revolutionary and worthy as can be.

If Mukhtar were to come back to life, would he choose to return to Egypt this time around? Would politicians -- similar to Wissa Wassef in May 1920 -- urge the masses to "pave the way for brilliant Egyptian talents so that they do not have to work in Europe and be ignored in Egypt"? And supposing that he indeed could return, would he see his work devolve again into an emblem that the orchestrators of a revolution need for the recruitment of the masses? These are questions that will not be answered here.

The art world, with its museums and institutions, residences and exchange programs, curatorial platforms and diverse exhibitions, is finding itself becoming more an arena for ethnography, politics, and cross-cultural diplomacy than a space dedicated primarily for the evaluation of form and aesthetics. Just think of the number of exhibitions, talks and symposia that happened over the last few years in an attempt to define the Middle East and Middle Eastern art. And that was before the Revolution! As Claire Bishop contended in her 2004 essay "Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics," moral and political verdicts have replaced art criticism and are often too summarily employed to substitute for a lacking in formal and aesthetic quality. Political agency has come to exonerate bad art. But, one hopes, not in post-Revolution Egypt.

Sam Bardaouil is a curator, writer and performance practitioner who lives and works in New York, Munich, and Beirut. He has curated numerous exhibitions such as "Iran Inside Out" at the Chelsea Art Museum and "Told Untold Retold" for Mathaf: The Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha. His play "When It Rains Bags" was adapted into the feature film "Here Comes the Rain," which was recently awarded the "Best Narrative Film from the Arab World" at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival, "Best Actor" at the Brussels Independent Film Festival, and "Best Director" at the Oran International Film Festival. In 2009, he co-founded Art Reoriented with Till Fellrath, a curatorial platform that focuses on contemporary art connected to the Middle East. The opinions expressed here are the author's own.

-Sam Bardaouil, ARTINFO

More of Today's News from ARTINFO:

A Chinese Vase Estimated at $800 Sells for a Staggering $18 Million at Sotheby's

Antiquities Looting During Egypt's Revolution Was Worse Than Feared

5 Indications That Las Vegas's Glitzy Art Gamble Has Gone Bust

Elizabeth Taylor's Spellbinding Beauty Captured in Persian Photos at LACMA

Christian Boltanski Takes a "Chance" With a Somber Amusement Park Ride for France's Venice Biennale Pavilion

Like what you see? Sign up for ARTINFO's daily newsletter to get the latest on the market, emerging artists, auctions, galleries, museums, and more.