In the season of heavy-hitting antiques trading that opens each new year, including the Americana sales at Christie's and Sotheby's in New York, the Winter Antiques Show in late January at the Park Avenue Armory is the flagship event, presenting the most blue-blooded, blue-chip material that dealers can summon. As of three years ago, the show pushed its qualifying cutoff date for that material forward to 1969, so that a broad swath of 20th-century design is now on view. Alongside the Queen Anne mirrors from Cotton Mather's family, the medieval miniatures, and the stone-robed Dianas, you might find Billy Baldwin slipper chairs, Samuel Marx secretaries, and Axel Salto ceramics.

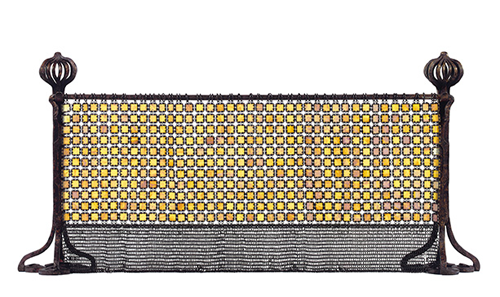

A farvile glass and wrought-iron fire screen (c. 1905) from Tiffany Studios fetched $1,665,000 in their December 2007 sale of important works of art

/ Courtesy Christie's

The question remains: Is there a blue-chip category in modern design? The short answer is yes. The 20th-century market is still a bit wet behind the ears, but it has matured significantly. "We now have 15 years of auction data," says Richard Wright, director of Wright, the Chicago auction house that specializes in modern design, "and are getting some idea of the quantity of material, which can be hard to know when a new area first emerges."

As with stocks, there is no magic list. The term "blue chip" might be applied to a designer's oeuvre or a single design, to a piece of great rarity or a mass-produced item of great aesthetic value -- a matter upon which experts rarely agree. And the market remains a "scene" driven by fashion, easy money, and press: The A-list cocktail previews at Phillips de Pury & Company in the early 2000s, when prices started to ascend, have given way to buzzing crowds at fairs in Basel, Miami, and Milan.

Judging from the big December sales, when 20th-century decorative arts and design go to auction, the fizz is fizzling, and the market is becoming more serious. Growing up is never easy. Mature markets look at more sober things like provenance, condition, and aesthetic and historical importance. Powerful conservative players have entered the field from the four corners of the globe, with staggering budgets and a new demand for blue-chip items. Some material is beginning to show inherent steadiness.

What is blue-chip in today's design market?

"Tiffany," says Joshua Holdeman, the international director of 20th-century decorative arts and design at Christie's. "Across the board, totally rock solid. The Tiffany market has never taken a hit." Indeed, it has been unfashionable yet strong, appearing in Christie's post-sale "highlights" press releases for the past 10 years.

Jodi Pollack, the head of 20th-century design at Sotheby's New York, concurs. "Tiffany is our biggest market in terms of sheer sales," she says, "and the deepest market in terms of collector base." Tiffany sales over the past five years at Sotheby's New York totaled roughly $35 million, almost 30 percent of the 20th-century design department's five-year sales total of $123.9 million. Pollack adds that the trophy properties are going overseas to Asia and South America -- to newer buyers who associate the Tiffany Studios output with Tiffany & Co., the chain of jewelry stores -- as well as to Europe.

"It's an international brand," says James Zemaitis, Sotheby's senior business developer for 20th-century design in North America. In short, Tiffany has become a mark of status -- always a driving force in collecting decorative arts. New buyers are also decorating with Tiffany. And it's not just affluent couples working with architects in Tribeca and on Nob Hill; it's also people with big Tudor houses in Shanghai and Rublyovka. Other items benefit from the same aspirational approach. (Nakashima dining table? Check. Perriand bookcase? Check.)

Established hot-spot categories like important French Art Deco are showing well and are here to stay. A pair of Gonse armchairs, 1930-32, by Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann, took in $1,426,500 (est. $600,000-800,000) at Phillips in New York in December. At Christie's, a pair of Eileen Gray lacquered divan blocks from 1923 went for $326,500 (est. $150,000-200,000). Gray's work exemplifies what experts consider true blue chip: It's important, there isn't much of it, and the right people owned it. Gray was recognized in her lifetime and celebrated by a coterie of connoisseurs who commissioned work, but she was forgotten after her death. She was rediscovered in 1979 as the subject of a major exhibition at London's Victoria & Albert Museum that traveled to the Museum of Modern Art in New York the following year. A Gray club chair set a record for 20th-century design -- $28 million -- at the Yves Saint Laurent sale three years ago.

A Charles and Ray Eames lounge chair with ottoman also can qualify as blue chip -- even if it is mass-produced -- as long as it's the right example. "There's been a trend away from mass-produced pieces," Peter Loughrey, director of Los Angeles Modern Auctions, says of blue-chip buying. "They don't appeal to the Lauders and the Brants of the world." But, he adds, "significant designs will always have buyers." With the Eames chair, first made in 1956, he explains, "you want rosewood, the way the designers intended it, black leather, and down fill, as before 1988. Sometimes you want the first year, but in the lounge chair you just want a really great one -- a 1970s one." And if it's a Billy Wilder Eames lounge chair -- a great friend of the Eameses, the director owned several during his lifetime -- you're golden.

The Eameses are the modern design market's first great morality tale, heroes and then victims of a new and naive market. Their work virtually kicked off the craze for mid-century collecting more than 10 years ago, skyrocketed in price, and then dropped from a great height as the market was flooded with material and fashion moved on. But they have remained buoyant -- as good a definition of blue chip as any. "They're not on the lips of editors at shelter magazines or collectors with their own museums, but they've continued to go up now at a nice pace," Loughrey says. Eames chairs did well at Sotheby's in December. Among other lots, a pair of molded-plywood DCWs from the 1950s (the acronym stands for dining chair wood) sold for $16,250, more than twice the presale estimate of $5,000 to $7,000.

Loughrey also makes a strong case that "blue chip" might refer not to the designer but to the design. "Noguchi was mass-produced by Herman Miller," he observes of Isamu Noguchi, the sculptor who also designed furniture. "But his Chess table was discontinued as soon as they started producing it -- a dozen were made in the prototype department. It has exclusivity, as it vanishes into institutions." Loughrey watched one sell for $4,500 when he entered the business in 1988, then $10,000 and $30,000. He sold one last December (est. $30,000-40,000) for $187,500.

Similarly, Robert Aibel, director of the Moderne Gallery, in Philadelphia, which specializes in American studio woodwork and exhibited at the Winter Antiques Show, has watched the George Nakashima Kornblut case, a small cabinet designed in 1963, increase from $6,000 -- Aibel's price in the late 1980s -- to $17,500 in the 1990s, to $35,000, his asking price now. Although a Kornblut case sold for $79,000 at Phillips in 2008, Aibel says he is pricing the piece to sell, observing what he believes the blue-chip "curve" really calls for.

For Hostler Burrows of New York, which specializes in Scandinavian design, blue chip has meant ceramics, in particular work by Axel Salto. A tall, spiked form that routinely sold for $8,000 to $10,000 in the late 1990s was selling for $15,000 less than a decade later. Kim Hostler says that an example sold at the Winter Antiques Show in January for more than $20,000. As Scandinavian design has become popular and its names more widely known, the heat of the market for early favorites like Finn Juhl or Hans Wegner has cooled, but the field has settled into a more predictable -- that is, safer -- rhythm of collecting. "It's gone from nobody being able to pronounce the names to having international appeal," Hostler observes. "There are shops in Paris, Milan, Japan. You can go anywhere and find it."

Liz O'Brien, who also exhibited at the Winter Antiques Show, says, "I never advise anyone to buy speculatively." For her, blue-chip items are "things that are a good value today that you love and want to live with. If a table trading for $10,000 suddenly trades for $30,000, the next time it might not be a $30,000 table." About a currently fashionable designer, she adds, "I still buy John Dickinson, but erratic auction prices have made it difficult. I wouldn't not buy it, but you just have to be picky."

For living contemporary designers, like Marc Newson and Ron Arad, who are old enough and celebrated enough to have entered the secondary market, blue-chip status can mean escalating prices for early pieces, made before there was support from manufacturers or galleries, even as the market remains cool to later work. Newson's Lockheed lounge sold in 2009 at Phillips in London for $1.6 million -- then a record for a work by a living designer -- and the prototype fetched $2.1 million the following year at Phillips in New York. The lounge, designed in 1988 and of which perhaps 10 were made (the figure has been adjusted upward several times), is a piece most top-tier collectors would pursue. But a Newson Chop Top table, from an edition of 12 (including a prototype) commissioned by Galerie Kreo, in Paris, failed to sell at Phillips last December (est. $180,000-220,000), though the gallery sold 10 of the tables at Design Miami in 2006 for $170,000 a pop.

Experts agree that the strength of the design market is at the very high end: Collectors are paying strong prices for extraordinary things. "The top end of whatever market -- whatever you can afford -- is the safest place to be," says Wright in Chicago, adding that his fundamentals for blue chip are, first, the historical importance of the designer -- distinct from the fashion of the moment -- and then: "Is it early, is it seminal, is it rare? Plus condition." With those criteria in place, he points out, the designer might be anyone from Gustav Stickley to Carlo Mollino.

The middling material of middle affluence -- "decorator modern" designers like Samuel Marx and average examples of architects' furniture -- is not doing well. Flush fashionable markets of the past five years, when well-heeled collectors were lining up for pieces by Jean Prouvé, remain strong but are softening as buyers reassess the rarity of material. Not every rusted school desk that came out of India and Africa back when surging prices sent people beating the bric-a-brac out of the bushes for colonial government commissions is worth top dollar today. While great Frank Lloyd Wright or Greene & Greene won't go begging, selected pieces by Rudolph Schindler and Paul Rudolph at Sotheby's didn't find new homes. Bodies of fresh-to-the-market material from unique architectural commissions, like the Gio Ponti furniture from the Villa Arreaza in Caracas, at Wright in December, sell well. But important site-specific designs, like the suite of Jean Dunand lacquered panels at Christie's from the breakfast room of the Templeton Crocker apartment, in San Francisco, do not. They can't be placed easily in a new environment.

The hard reality of the design market, even at stratospheric levels, is that people are usually buying to furnish as well as to collect. In blue-chip terms, that means a Nakashima occasional piece -- a 20-inch-wide side table sold at Christie's in December for $35,000 -- might be more bulletproof in resale than a large statement piece. A 14-foot Nakashima dining table had no takers at Sotheby's the same month, probably because no one -- not even institutions -- had room for it.

"Curators don't like pianos and they don't like beds," says David A. Hanks, curator of the Liliane and David M. Stewart Program of Modern Design, in Montreal. Curators are generally a cautious lot, which can be useful in assessing an evolving market. Of the design fairs in Basel and Miami, Hanks says, "I never go. It's the worst of everything, the way things are marketed. I don't like looking at design under social and political pressure." Hanks, who for 30 years has helped the Stewarts assemble what is considered to be one of the most important 20th-century design collections in North America -- more than 5,000 objects, now a gift to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts -- says he prefers attending the annual Salone Internazionale del Mobile in Milan, where "furniture is sold to be used -- functional furniture, not furniture as 'art.'" Hanks also sees a disheartening trend in the elevation of what he calls "second-rate" designers like Paul Evans in lieu of first-rate material that is becoming scarce as it disappears into collections.

Diane Charbonneau, the curator of contemporary decorative arts at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, recognizes a danger in private collections' beginning to mimic public ones. "With most of the design collected today, it becomes a checklist: one of those, one of those," she says. Institutions feel obligated to represent a category widely for visitors. But private individuals, in seeking blue-chip pieces, are creating "best of" collections that are homogeneous, lacking personality and depth: the very things that an institution looks for in a gift, or that the market looks for in resale. A Bauhaus teapot sold at Sotheby's in December for $374,500 to a teapot collector; the presale estimate was $60,000 to $80,000. That collection as a whole is blue-chip for its focus, because it's greater than the sum of its parts.

Curators are good at considering the recent past, too. R. Craig Miller, the senior curator of design arts at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, is now assembling and installing one of the largest permanent collections of contemporary design to be put on display in the country, and he is busy buying up postmodern design. Its poor performance at market makes it attractively affordable.

"We're buying it as fast as we can," he says. "I think it's incredibly important." The market has had an ugly-stepsister reaction to the material, though its attributes should make it a darling among collectors. Postmodern design is handcrafted and historically distinctive, and it involves the biggest names of its period, Ettore Sottsass, Richard Sapper, Michael Graves, and Robert Venturi among them. A fresh assessment was offered recently in the exhibition "Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990" at the Victoria & Albert Museum. The show met with mixed reviews.

Miller makes a broad point, worth keeping in mind when evaluating trends in the modern market: There is less guesswork, and fewer "undiscovered geniuses," than the annual waves of excitement at galleries, fairs, and auctions would have you believe. (The December season's sale record was $7,474,500 for a flock of 10 epoxy-stone sheep from the 1970s by François-Xavier Lalanne. Is that lasting value, or just a lot of mutton?)

"I don't think reputations go up and down in the design field, as in the art market," says Miller. Citing Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and the Eameses, he notes, "The legendary designers are known and recognized in their own time."

Click the slide show to see works by the most market-approved modern designers.

This story originally appeared in the April issue of Art+Auction.

-William L. Hamilton Art+Auction, BLOUIN ARTINFO

More of Today's News from BLOUIN ARTINFO:

Like what you see? Sign up for BLOUIN ARTINFO's daily newsletter to get the latest on the market, emerging artists, auctions, galleries, museums, and more.