If Henry Miller were still alive on December 26, he would be 121 years old. "The Last Days of Henry Miller" was originally published in The Hudson Review in 1993. The piece below is excerpted from the original piece. One of the ironies of my life is that I was to meet both Anaϊs Nin and Henry Miller independently of each other when both were nearing the end of their lives. Nin died in 1977; Miller in 1980. I met Anaϊs in February 1974.

"Barbara - This is Anaïs Nin speaking. I have read your work and I think it is very good. We have many affinities. I would like you to come and see me."

Several years later I met Henry Miller. The meeting came about as a result of "An Open Letter to Henry Miller" that I wrote and broadcast over KCRW in 1977. Someone -- to this day unbeknownst to me -- took a tape of the program to Henry, and shortly after the broadcast I received an invitation from his secretary telling me that Henry wanted to meet me. Would I be able to come for dinner?

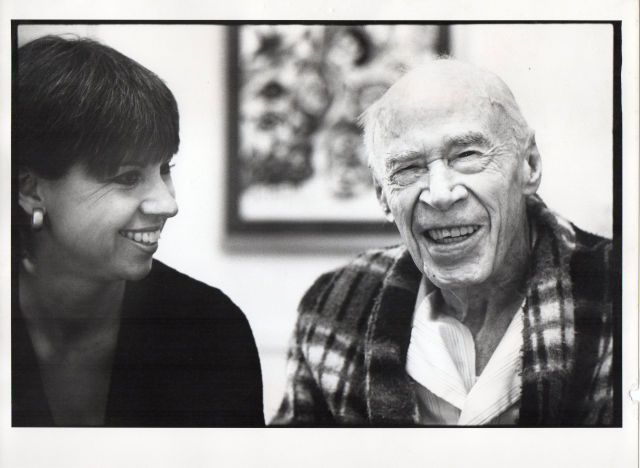

Last Days of Henry Miller by Barbara Kraft

(December 26, 1892 - June 15, 1980)

That last year he shuffled between his old-fashioned, high-set, walnut-dark bed, the desk at its foot, the Ping-Pong table in the lanai on which he now painted, a more sedentary kind of play for an octogenarian, and the dining table, in fact, a redwood picnic table covered with a cloth. This is where he held court every evening attired in his bathrobe, plaid or blue terry cloth, pajamas, fluffy white bedroom slippers and white socks. He was a tough old bird, rather like a turkey, with his croaky voice, heavily veined, creped hands, parchment-thin skin, wattled throat and indomitable, naked head.

As his body failed him, the eyes, the ears, the bowels, the bladder, the bones, he shrugged his shoulders and with head held high said, "We must accept what comes, don't you know." And then he would return to the arduous business of folding the napkin in front of him. The long-fingered, still graceful hands, bruised and etched with coagulated arteries, slowly smoothing the cloth, folding it in half, in quarters. This accomplished he would labor to roll the napkin up, fitting it, at length and with considerable effort, into the monogrammed, silver napkin holder that marked his place at table. One tiny island of control that could still be mastered with great concentration.

The word he used to describe his condition was apocatastasis, a Greek word meaning "restoration" and referring to the eternal round made by the planets which restores a state of being. The word also refers to the doctrine that Satan and all sinners will ultimately be restored to God. Though Henry accepted what was happening to him, there were moments when he flapped his wings in annoyance, an appropriate response for a man who had steadfastly refused to be overcome by anything. "You think for the man of great spirit it [death] should be a graceful thing. A just going to sleep and yet that isn't necessarily true. It could be awful, ignominious."

His humble efforts to carry on with his life were at times moving, at times exhausting, at times hysterically funny and at all times immensely and universally human. For Miller was not and never desired to be "somebody" in the sense that today everybody is somebody. Either through their own earned or unearned celebrity or through some vicarious attachment to celebrity. Miller was anybody and everybody, a meat-and-potatoes man, an ordinary bloke according to the literary critic Alfred Kazin, a man who would rather be at peace with himself than a writer according to his friend, the writer Wallace Fowlie. Although, with all due respect to Mr. Fowlie, Miller's rapprochement with peace was achieved by writing which ordered and transformed the Milleresque chaos into a turbulent and teaming celebration of life on its own terms.

Henry described himself as a plain, down-to-earth, simple man. He was also a genius who, if reincarnated, wanted to come back not a genius but an ordinary man, a horticulturist, as he told me one evening over dinner. No, I was not one of Henry's "ladies;" I was one of his "cooks" and Friday was my night chez Miller. On this particular Friday evening, some six months before he died, I had to awaken him to come to the table. A punctilious man, he was orderly in all his habits. His pens, pencils and paper in their proper place on his desk, his watercolors, his paintbrushes neatly arranged on the Ping-Pong table, his dinner served at 7:00 p.m. The dedication to list making over the years. The famous, framed lists of places he had been, of places he had not been, lists of favorite foods, lists of favorite piano music, lists of women he had never slept with. Behind that Buddha-like equanimity lurked a Germanic heritage.

Usually he was up waiting for me but of late he had become so weak that he was no longer able to navigate alone the distance between bedroom and dining room. Debilitated by malnutrition, not an uncommon affliction of old age, and a kind of palsy, possibly caused by petit mal seizures, he was quite frail. His hands trembled, he was paralyzed on one side, deaf in one ear and blind in one eye, so he said, although he regularly commented on what I was wearing down to a pair of green suede cowboy boots I once showed up in. When sight failed him, his sense of smell came to the fore. "I can smell your perfume, Barbara. Hmmmmm. I can barely see anymore but I can still smell." The full lips gathered into a lopsided grin, exposing teeth that remained remarkably virile.

I roused the slight body that was all but invisible under the satin-covered, down comforter and eased him into the waiting walker. At dinner that night he spoke about how he would come back "a man who tends flowers. Not a genius, or a writer, that's the worst." Pressed, he elaborated on what writing entailed, his eloquent, age-marked hands raised in decisive exclamation. "It's a curse. Yes, it's a flame. It owns you. It has possession over you. You are not master of yourself. You are consumed by this thing. And the books you write. They're not you. They're not me sitting here, this Henry Miller. They belong to someone else. It's terrible. You can never rest. People used to envy me my inspiration. I hate inspiration. It takes you over completely. I could never wait until it passed and I got rid of it."

But he never did get rid of it. Of inspiration. Nor did he rid himself of his obsession with woman, with eros, with life itself. Woman, eros and life were vital to Miller's sense of himself, imbued with a mystery and a magic which compelled and obsessed and bemused him without letup until June 7, 1980 -- the day his eternal round was completed.

"I keep my nose to the grindstone," he said. "Old age is terrible. It's a disease of the joints. It's awful when I get up in the morning. I can barely bend over to brush my teeth. It's only when I get to work solving problems that I forget about it."

Beset by a multitude of infirmities the last decade of his life, Miller worked as furiously as ever producing several books (among them the three-volume Book of Friends) and hundreds of watercolors. He continued to maintain his voluminous correspondence with the world and entertained a seemingly inexhaustible stream of visitors which ranged from Vietnamese immigrants to celebrities like Ava Gardner, Governor Jerry Brown and Warren Beatty who was then filming Reds in which Miller appeared in a cameo role.

In between were people who came to interview him, academics who came to write about him, and film crews eager to commit to videotape the passing of an era. Some he performed for, some he insulted, others he beguiled. He had a striking photograph of the young Ava Gardner in his entrance hall which hung next to a framed list of his favorite cock and cunt words. When the lady came to visit in the flesh Henry overheard her chauffeur asking, as they left, where she wanted to go. According to Miller, she responded "Anywhere. Just anywhere." Henry found that a remarkable answer. In August of 1978, Jerry Brown, accompanied by his entire entourage, paid a call at Ocampo Drive. Miller was in one of his wicked moods, being wicked was a pure delight to him, but he was never malicious. He greeted Brown, saying, "You know I think politicians are the scum of the earth, next to evangelists. I can't stand Billy Graham." Henry had a way of benignly saying outrageous things. Having said them he would sit back, a cat pawing a mouse, a crooked smile playing expectantly around his lips, waiting for the response his words would elicit...

Nearing the end a crazy strength coursed through his failing form, the terrible energy of the dying. One night, forgetting he could no longer walk, he managed to get into the bathroom where he closed the door before collapsing. The bathroom, as legendary as his lists and charts and part of the Miller lore, was covered floor to ceiling with photographs of friends, naked women, idols such as Nietzsche and Lawrence and gurus like Krishnamurti and Gurdjieff. When he was found by Bill Pickerill, he was gesticulating and talking to some image on the wall, calling, "Monsieur, Monsieur." According to Bill, Henry looked up calmly and said, "Oh, Bill, I'm so glad to see you again. How good that you're passing by just now. I'm having the damnedest time with this guy."

With all of this transpiring, it wasn't sad in that house, at that table, in that bathroom. Touching, yes. And moving. And immensely human and funny too. For Henry was a man at peace with himself. He had acted out and lived his beliefs. And when the by now rare "don't you know" crossed his lips, it was a burst of sunlight bringing tears to the eyes and a clutch of joy to the heart. One evening as he was being rolled off to bed he noticed my skirt which was bright red. Reaching forward, blind as he was, he gathered up the hem, stroking the material with his other hand, exclaiming how wonderful it was that I always wore such beautiful clothes.

In May of 1980, one month before Henry died, the Rumanian-born playwright Eugene Ionesco was visiting Los Angeles. I was doing an interview with him for National Public Radio and in the course of our meetings I mentioned that I knew Miller. Ionesco, eager to meet Henry for whom he had great admiration, asked if I could arrange it. No two men could have been more different. Ionesco all doubt and despair, fixed on the contradictions, consumed by anguish; Miller, all accepting, preaching surrender, abdication and a self-created paradise, pure light. Yet they shared a reciprocal esteem for each others work. Their starting point was similar; their roads different. The meeting never occurred. Henry demurred, saying, "Oh, I don't want him to see me like this, how I am now." Adding a few minutes later, "If Ionesco could see me now, that's something he could write a play about." Instead I took a set of books inscribed to Ionesco from Miller.

When the end came it wasn't awful, it wasn't ignominious. It all happened very simply and was just short of a "going to sleep." Henry died at home in his own bed in the arms of Bill Pickerill on a Saturday afternoon. I end this memoir with Miller's own words, words written about Auguste, his clown, in The Smile at the Foot of the Ladder: "Perhaps I have not limned his portrait too clearly. But he exists, if only for the reason that I imagined him to be. He came from the blue and returns to the blue. He has not perished, he is not lost. Neither will he be forgotten."

Reprinted by permission from The Hudson Review, Vol. XLVI, No. 3 (Autumn, 1993). Copyright © 1993 by Barbara Kraft