Our homeland is in ruins. All that's left are the stories of grandparents who have shaped the history behind today's Syria. Our contemporary history can be defined as follows: Successive wars, defeats and independence. Today, we reap the positives and negatives of that history. I will now tell you a story, told to us by a man who has played a part in building Syria's not-too-distant history -- a man spent his life breathing and loving the air of Homs.

I used to hear this story the same way every time. We used to have lunch on the balcony in my grandfather's house in Homs. He would wear his favorite grey robe, as he held a fruit my grandmother picked from a tree in the garden in one hand, and a knife in the other. His grandchildren gathered around him, excited to hear the story, as they chewed on peaches and apples, the Homs breeze caressing their fascinated faces.

My city sits on top of a highland, approximately 400m above sea level, with a window overlooking the Lebanese Akkar Plains. It is graced by a soft breeze, laden with the scent of the Mediterranean sea, giving the Homs air an unmatched splendor.

My grandfather took us to 1945, a time when there were nationwide protests against the French occupation of Syria. He told us about a student who would sneak out of school and join thousands of other students flooding the streets of Homs. They chanted patriotic slogans and carried signs saying: "Syria is for the Syrians" in both Arabic and French.

A few minutes into the protest, the 17 year-old slowed down, slipped into an alley, and leaned against the wall to study for his upcoming test.

The old Sa'a Square was blown up, and street carts were set ablaze and turned to rubble. The Grand Homs Pharmacy was looted and damaged.

That boy was my grandfather, Suhail AlQusir. He has repeated stories from his youth to his grandchildren for many years, and they have shaped our knowledge of our history.

The breeze carried with it specs of water from the fountain in my grandfather's garden. He proudly said that he wouldn't have sacrificed one hour of studying time to protest against France, which had occupied Syria after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I. The French presence was never welcome in Syria, and Paris consistently tried to quench resistance movements in the first half of the 1920s.

My grandfather was born in 1927, in the thick of the wave of anger and rebellion against the occupation. He was the youngest among 8 brothers. His mother passed away in 1945, during his bachelor degree exams. The same year, the independence uprising began. Shortly afterwards, France withdrew and the Syrian republic was established.

My grandfather inherited 70 golden Liras from his father. His two older brothers urged him to save the money, and work for them in one of their family shops -- but my grandfather had other plans.

He traveled to Damascus to study pharmacy at the Syrian University, which was the only university in the country at the time. Its name was later changed to the University of Damascus, after the establishment of a second university in the city of Aleppo in the late '50s.

The flashy capital did not distract my grandfather, and he managed to lived a simple life to save his inheritance money. He graduated with honors in 1950, and was handed his certificate by Syria's first president following independence, Shukri Al Quwatli. He put that certificate in a bronze frame and hung it on the wall of the Grand Homs Pharmacy that he opened later that year.

The Grand Homs Pharmacy was set up in downtown Homs, on a bustling street busy with vegetable and spice vendors, bookstores and shops, opposite the old Sa'a Square.

For the first few months after he opened it, the young pharmacist would take the medicine bottles out of their boxes and assemble the bottles and containers attractively. He worked from 7am to 11pm on weekdays, and spent the night at the pharmacy on Fridays to serve customers all night.

Due to its location and long operating hours, the Grand Homs, the 7th pharmacy to open in the city, quickly became the most famous.

With the money he made, my grandfather bought two gold Liras every week, which he kept in a green metal box that he still has in his room. That was the ideal saving plan for the majority of the inhabitants of the city, who didn't have the faintest idea of how banks worked.

When my grandfather turned 30, in 1957, he bought a piece of land in a upperclass neighborhood and constructed a four-story house. He then courageously asked one of the most influential businessmen in the city for his 20 year-old daughter's hand in marriage.

Things were looking good for my grandfather. He purchased stock in sugar and cement factories, and later got together with four other pharmacists to establish a medicine factory they named "Medico."

But his good luck didn't last very long. In 1958, Syria and Egypt unified under the rule of Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, who ordered the nationalization of private companies. My grandfather lost all his investments overnight. As for the medicine lab, it barely covered its costs.

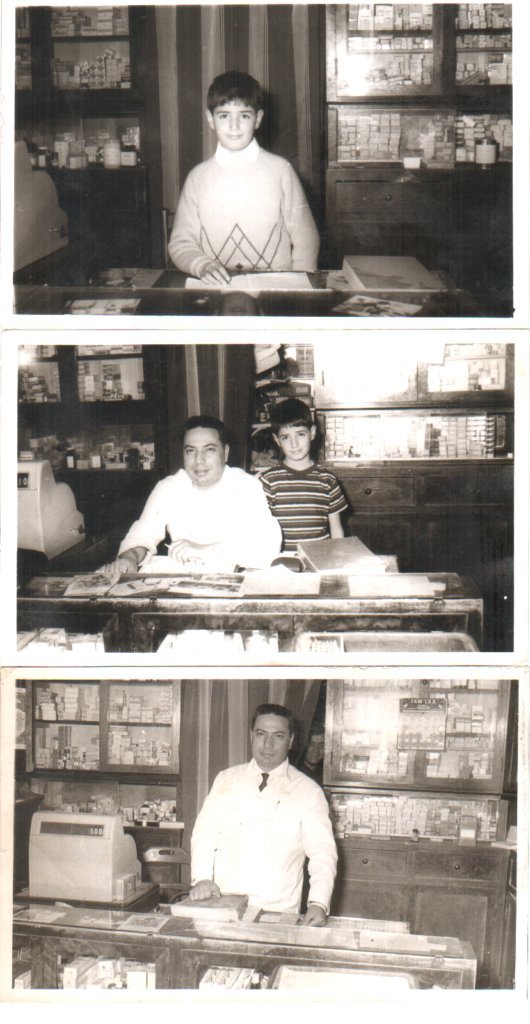

My grandfather and his sons in the Grand Homs Pharmacy (From the archive of Dr. Ghassan Qusir).

My grandfather and his sons in the Grand Homs Pharmacy (From the archive of Dr. Ghassan Qusir).

This does not mean that my grandparents did not have a revolutionary path of their own. My grandmother, Radya ElSeba'i, was a lot like her husband. She was one of the very first women in Homs to drive a car. She drove a white Opel to the pharmacy at the end of each week to deliver the folding bed to my father, and the children would run after the car in delight.

She laughs when she remembers how my uncle Nabil would hide his head under the car's dashboard from embarrassment as she drove. My grandmother did not defy traditions out of principle -- she did it out of necessity. Being with her five children as her husband worked day and night required being able to move freely.

On a winter's day in 1970, my grandfather heard chants outside the pharmacy. He went out to find out the cause, and saw Hafez Al Assad, the leader of the coup d'etat and the country's new president, on the balcony of the Ba'ath Party headquarters, a few meters from his store. It was Al Assad's first visit to the city since the army took over power in what was dubbed the "correctional movement."

As my grandfather served his customers, he could still hear the noise outside. There was a wave of optimism sweeping through the country at the time, as Syrians believed that Al Assad's rule would bring on prosperity and economic stability. Despite the corruption and the political oppression, Al Assad's era witnessed developments in the private sector as the radical socialist policies of the former regimes decreased.

He has aged significantly over the past three years; his wrinkles have deepened and his silver hair is finer. He has grown sad and lost -- like the sadness and loss of Syria itself.

By the '80s, Assad had enforced a ban on medicine imports to reduce the country's trade deficit. As a result, the demand on locally produced medicine went up, and business boomed for "Medico" medicine lab. It quickly became the largest lab in Homs and later one of the largest in Syria.

My grandfather's fortune doubled, so he bought a villa near Damascus road and a beach house in the coastal city of Tartus and gardens in the village of El Houla -- which has now become known as the site of a massacre that took place 2012 -- as well as building a mosque that he named 'Mostafa' after his father.

My grandfather did not miss a single day's work He continued to wear striped, short sleeved shirts instead of formal shirts and suits that my grandmother always said were more appropriate for his age and position.

Even his circle of friends remained the same, it never grew to include businessmen or officials. My grandfather preferred a group of simple, pious men, who would accompany him to the villa after performing Friday prayers in the mosque. They brought skewers of roasted meat and and cheese-filled Konafa garnished with grated pistachios from Aleppo.

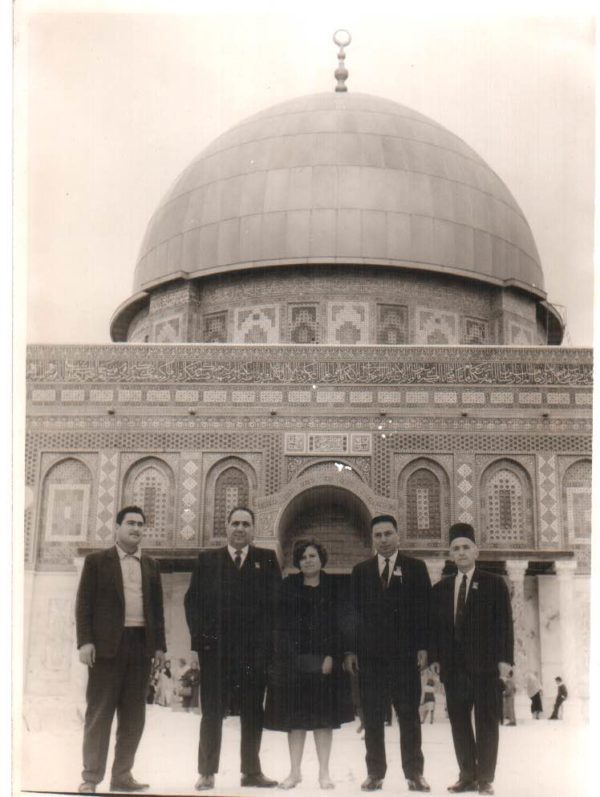

My grandfather (second from the right) with his colleagues in Jerusalem during a conference for the Arab Union of Pharmacists in 1966 (From the archive of Dr. Ghassan Qusir).

My grandfather (second from the right) with his colleagues in Jerusalem during a conference for the Arab Union of Pharmacists in 1966 (From the archive of Dr. Ghassan Qusir).

On a Saturday evening in the summer of 2000, life suddenly stopped in front of the Grand Homs Pharmacy at the old Sa'a Square, where was a picture of the president with the caption: "Our leader forever."

Then, a TV presenter tearfully announced that Hafez Al Assad had died on official Syrian television. Shops closed their doors, including the pharmacy, and people left the streets: Everyone became anxious over what would follow the death of the immortal president. But the transition of power to Hafez's son Bashar was smoother than people expected.

The new president promised new economic reforms aiming at freeing the economy and encouraging foreign investment, but development projects and the privatization of the old industries owned by the state did not gain much benefit. The tight circle around the president and his trade partners gained the most.

Assad's cousin Ramy Makhlouf monopolized a network of profitable companies and became one of the richest men in the country. In the eyes of Syrians, he became a symbol of corruption.

Eyad Ghazal, one of Al Assad's friends was appointed governor of Homs. Ghazal promised to revive the city's economy through a project that was given the romantic name of "Homs's Dream." The project set out to demolish large parts of the city's historic center and market and replaced them with skyscrapers and modern shopping malls to mimic -- on a smaller-scale-- the city of Dubai.

Lands started being confiscated by 2009, and shop owners realized that it would soon be their turn. Even the Grand Homs Pharmacy which had by then been open for six decades, was threatened.

He is constantly wondering if he is ever going to be able to reopen the Grand Homs Pharmacy. Maybe one day.

We can trace the rise of anger to that period. In March 2011, a protest erupted nationwide, calling for freedom, democracy and the elimination of corruption -- and it was not easy to contain. Only two weeks after the start of civil movement, protests erupted in the center of Homs,near the Grand Homs Pharmacy. Protesters started by expressing their anger with Makhlouf and Ghazal, but they quickly started to call for the removal of Assad himself.

Security forces responded with an oppression campaign that produced hundreds of casualties in the first few months of the uprising.

My grandfather spoke of that period with the same spirit with which he told the story of the 1945 uprising. It was clear that he did not want his grandchildren to become distracted from their education and self-development. He understood their hopes and aspirations, as well as their anger, but he said that nothing was worth dying for.

Like most business owners in the center of the city, my grandfather tried to keep his pharmacy open -- but with the escalation of the violence in the beginning of 2012, he was forced, for the first time since 1950, to close its doors.

Rebels took over parts of the city, including the area where the pharmacy is located, and the government used its military arsenal to take back the areas it had lost control over. The army's artillery destroyed buildings around the pharmacy. The old Sa'a Square was blown up, and street carts were set ablaze and turned into rubble. The Grand Homs Pharmacy was looted and damaged.

When the conflict intensified, my grandparents moved to Damascus, where they were both born. My grandfather started roaming the streets, entering every pharmacy he passed to browse its products. He asked pharmacists to stand aside so that he may stand behind the counter for a few moments to relive the role of a pharmacy owner.

When my grandparents returned to Homs, his sons helped him set up a small pharmacy in the neighborhood of Al Wa'r, which had become a refuge for thousands of families who have lost their homes in other parts of the city. But when clashes erupted in Al Wa'r a few months later, a missile landed right in the middle of the new pharmacy. Luckily, it was closed at the time.

My grandparents have now returned to their villa. My grandmother has gone back to taking care of the roses and the apple trees, and my grandfather spends his time reading the Quran and watching the news, which shows him that his country is collapsing all around him. He is constantly wondering if he is ever going to be able to reopen the Grand Homs Pharmacy. Maybe one day.

I think his days go by slower now. He has aged significantly over the past three years; his wrinkles have deepened and his silver hair is finer. He has grown sad and lost -- like the sadness and loss of Syria itself.

My grandfather told me lately: "There is no bag big enough to contain a life." Life has become scattered around every corner of our destroyed city. The memories have become more painful, as we witness the demise of a homeland we have loved, lived and breathed in all its states.

This post first appeared on HuffPost Arabi. It has been translated into English and edited for clarity.

This post originally appeared on Al Jumhuriya.