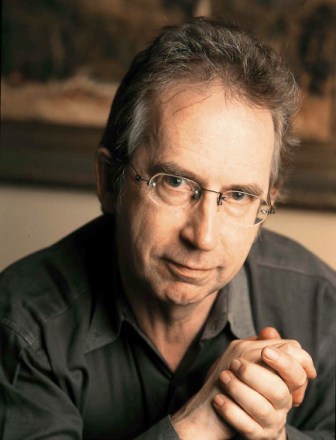

Over the past thirty-five years few authors have written with the skill, consistency, and imagination of Peter Carey. The Australian-born novelists' ability to weave disciplined research and compelling  prose, coupled with his sheer brilliance as a storyteller, has twice garnered him the prestigious Man Booker Prize, and his most recent novel, Parrot and Olivier in America (Faber & Faber, 2010) was recently shortlisted for a third. Last week, I sat down with Peter to discuss his life and work.

prose, coupled with his sheer brilliance as a storyteller, has twice garnered him the prestigious Man Booker Prize, and his most recent novel, Parrot and Olivier in America (Faber & Faber, 2010) was recently shortlisted for a third. Last week, I sat down with Peter to discuss his life and work.

Ben Evans: Do you find yourself, still, at this point in your career, getting better as a novelist? Can one continue to learn even after eleven novels and a mantle of awards?

Peter Carey: I have never begun a novel which wasn't going to stretch me further than I had ever stretched before. For instance, I am presently working a novel with two voices. One is a woman in London in 2010, the other a man in Furtwangen, Germany in 1854. They will never meet. They will not fall in love. It is obviously an impossible thing to do, but today, at least, the thing I didn't know how to do is working like a dream.

BE: As a writer grows older is there an urgency to produce more work?

PC: I'm certainly working longer hours. Sometimes I think this is to do with my age (67) and the question of how few books I will write before I die or lose my wits.

But then there's the question of my sons who are now 20 and 24. They just don't need me to cook for them or pick them up from school. So yes, I write more. How else am I going to fill my empty time?

BE: How is the quality of contemporary American literary fiction affected by its presumably declining readership, if at all?

PC: I just read Freedom. It's a great book and Franzen is a great writer and that will not be diminished by either mad jealousy or a shrinking market for literary fiction.

BE: Do you find it easier approaching a novel within a historical framework like True History of the Kelly Gang or Parrot and Olivier in America, or is it more difficult to write a book like The Unusual Life of Tristan Smith, where everything is created from scratch?

PC: The great thing about using the past is that it gives you the most colossal freedom to invent. The research is necessary, of course, but no one writes a novel to dramatically illustrate what everybody already knows. I go to the past to illuminate the present, but also to make up weird shit. I use research for lots of reasons but one of them is to make the weird shit bullet proof.

Here is the most perfect thing anyone said about Oscar and Lucinda (Jonathan Miller in fact) "Oh, I see, it's a sort of science fiction of the past."

And yes, a completely invented world brings certain degrees of difficulty. Does Shakespeare exist in the world? The people speak English, but what sort of English? How is their invented history contained in their slang? What sort of trees and shrubs grow there? What are these plants called and how do they look? Et cetera, and so on, forever.

BE: You've said that as a writer, the personal doesn't interest you, nevertheless it seems inevitable that an author's own experience will creep into his/her work at one time or another, are there any instances of this you can recall in your fiction?

PC: I have written a memoir here and there, and that takes its own form of selfishness and courage. However, generally speaking, I have no interest in writing about my own life or intruding in the privacy of those around me. My greatest pleasure is to invent. My continual mad ambition is to make something true and beautiful that never existed in the world before.  To achieve this I will use whatever is at my disposal. For instance, I just gave your name to a character in my new book. I don't really know you, so this character can't be like you in any way. But I stole your name and stuck it on the page much like, I imagine, Robert Rauschenberg might pick up a sock, glue it to a canvas and paint over it. It was a sock. Now it's a Rauschenberg. Same thing.

To achieve this I will use whatever is at my disposal. For instance, I just gave your name to a character in my new book. I don't really know you, so this character can't be like you in any way. But I stole your name and stuck it on the page much like, I imagine, Robert Rauschenberg might pick up a sock, glue it to a canvas and paint over it. It was a sock. Now it's a Rauschenberg. Same thing.

BE: You are the executive director of creative writing at Hunter College in NYC. Can good writing be taught? Or is it simply honed?

PC: Good writing of course requires talent, and no one can teach you to have talent. It also needs amazing will (so if one is recruiting students one looks for both of these qualities together).

Your role as teacher is to nurture and protect your students while, at the same time, forcing them beyond their limits, encouraging them to see the world, to imagine every action in the moment, to see the body as part of dialogue, and basically to write as if their life depended on it. If we were discussing tennis, we'd agree that a good coach can dramatically lift a player's game. That's what Colum McCann, Nathan Englander, and I do at Hunter College. We're working writers, every day. We're as driven and obsessed as our twelve fiction students.

BE: Even though you keep away from personal experience, is writing catharsis for you?

PC: It is intensely emotional and hugely demanding. One spends ones' day in a very weird place. It would be dramatic, even ingratiating, to say it was cathartic, but I just can't bring myself to do it.

BE: One Peter Carey novel survives, it is mandated that it never go out of print as long as human kind exists, you get to choose. Which one is it and why?

PC: Tell the bastards, burn them all.

Parrot and Olivier in America can be purchased here.