Watch the TEDTalk that inspired this post.

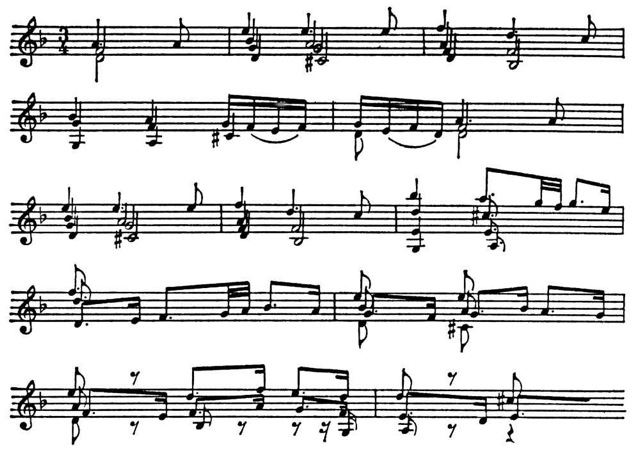

The composer's wife had died suddenly; violently. Here, at the premiere of his latest piece, the audience whispered that this new song must be a tribute to her memory. From the first notes, vast choruses of voices seemed to tear themselves from the strings of a single violin -- gnashing in conflict, pleading for understanding; howling beyond the reach of words.

Despite the Chaconne's harrowing nakedness, none of us can know just how it felt to be Johann Sebastian Bach as the piece's strains first poured from his pen. Although the composition conjures up, as the composer Brahms wrote, "a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings," the original of that world belonged -- and still belongs -- to Bach alone. We can guess intuitively at his thoughts; try to feel how we imagine he felt -- but no matter how closely we listen, we can never fully know how it felt to be him in those moments.

And after all the centuries since Chaconne, we're still struggling to understand just why that is.

We probe at human consciousness today in ways that would've seemed outright magical to Bach. We slice through brains digitally, leaving them alive and intact, and watch electrochemical symphonies echo within their hemispheres. We pin down patterns of human brain activity -- precise neural circuits, even -- whose presence can tell us that a mind "has a Self in it." We can digitally examine animals' dreams and memories, record them and play them back. We can even extract visual images straight out of the brain, to replay for an auditorium of viewers. And not one bit of this gets us much closer to understanding what exactly it's like to be you.

Our minds are choruses -- voices singing together in many keys; sometimes harmoniously; other times... not so much. -- Ben Thomas

Take Jill Bolte Taylor's TEDTalk, for example. She describes the experience of watching helplessly as her mind closed down, one section at a time -- but even as her internal chatter and linear logic and bodily sensations fell away, a center somehow held firm: Through it all, there was still something that it was like to be Jill Bolte Taylor.

As her experience shows, our minds are choruses -- voices singing together in many keys; sometimes harmoniously; other times... not so much. Themes, melodies and moods arise and pass away. Scenes play out; we cast our own minds in roles of younger, braver or raunchier characters. We smell Mom's oatmeal cookies and revert, fleetingly, to our childhood selves. We place ourselves in one anothers' "shoes" -- more to the point, in each others' minds -- which means that in your mind, there's a little idea of me playing out my part, while a little idea of you does the same in my thoughts.

And while all these things arise and pass on -- though memories and grudges can fade with time; though even your deepest attachments and expectations can be meditated (or medicated) away -- there still remains a certain position of perception; a particular and highly peculiar point of view that you can't help but call "me."

This, right here, is the real mystery of consciousness: Not that it can engage in dialogues with long-dead composers; not that it can weather strokes and amnesia and vegetative states -- and no, not even the fact that it can think about itself. Those are all fascinating traits; no doubt about it. But the real heart of the labyrinth is that, among all the curious phenomena of the known universe, only consciousness is first-hand.

It might sound silly to point out something so obvious -- but in the scheme of physical reality, its very uniqueness is astonishing. No matter how intimately we experience a sunset or a rock formation or a strand of DNA, we see it from the outside, looking in. Only in first-person consciousness do we find ourselves inescapably at the center -- and a deeply strange center, at that: One from which we can only look "outward" by looking "inward" on our own perceptions. Nothing else in nature seems remotely analogous to this everted quality of consciousness -- subjectivity baffles us, in short, because we have nothing objective to compare it to.

And yet, of course, we all know what it's like -- don't we? Bach tried to show us, in the most intimate way he knew, what it was like to be him. Dr. Taylor tries to tell us, in the most precise language possible, what it was like to watch her thoughts fall away as she fell into timeless bliss. Truth be told, though, your own subjective experience is just as unique as hers -- and, ultimately, just as immune to exact translation.

Maybe that's what the poet John Keats meant when he wrote, "Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter." When words and music fall silent, we're left alone with the inaudible melody of our own consciousness: The song none of us can ever truly share with another, though every one of us already knows its tune by heart.

Ideas are not set in stone. When exposed to thoughtful people, they morph and adapt into their most potent form. TEDWeekends will highlight some of today's most intriguing ideas and allow them to develop in real time through your voice! Tweet #TEDWeekends to share your perspective or email tedweekends@huffingtonpost.com to learn about future weekend's ideas to contribute as a writer.