The patient, most doctors agreed, was a lost cause. Occasionally she'd open her eyes; yawn or grunt; or even cry -- but these were mindless reflexes, the doctors said. The patient was vegetative, they explained: awake, technically, yes -- but unaware; dead to the world. It was time, they said, to consider removing her life support.

That is, until researchers learned to read her mind.

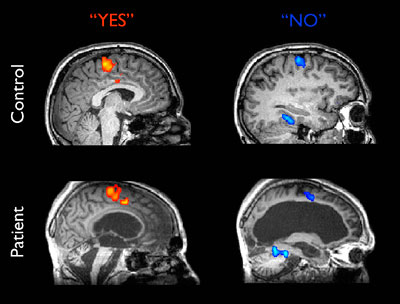

As they watched the patient's brain activity on an fMRI scanner, Drs. Adrian Owen and Steven Laureys asked her to imagine playing tennis -- and her brain's motor cortex lit up, clear as day. "Now imagine wandering through your home," they told her. Her spatial awareness centers burst into action.

"Now," they said, "think 'tennis' for 'yes,' and 'rooms in your home' for 'no'." They ran her through a "true or false" quiz. She got every question right.

She was one of the lucky ones. In study after study, Owen and Laureys -- and other researchers -- have discovered clear signs of active consciousness in dozens of vegetative patients. A 2009 study found that 40 percent of patients diagnosed as vegetative are at least somewhat conscious.

"Somewhat conscious?" What exactly does that mean? What's it like to have just "some" consciousness?

These are crucial questions not only for thousands of misdiagnosed patients, but for anyone who's ever gone in search of his or her True Self. Consciousness, these studies show, isn't a single discrete entity so much as a concert performance -- not so much a "ghost in the machine" as a whole armada of ghosts haunting an intricate network of machinery.

The Self has proven to be, if anything, an even more elusive quarry. Take, for example, cases of split-brain patients -- those whose left cerebral hemisphere has been surgically severed from the right. In these patients, each side of the brain develops its own personality, its own desires -- even its own beliefs. Neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran has studied patients in which one hemisphere claimed to be female; the other, male -- and in which one hemisphere professed belief in God, while the other stood firm in its atheism.

In other words, Self and consciousness aren't quite the same thing -- a Self isn't the consciousness itself -- it's that which is conscious. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio has said, "A conscious mind is a mind with a Self in it." But as these split-brain patients demonstrate, a brain's conscious experience isn't always limited to a single Self.

Meanwhile, here your own Self sits, insistent as ever upon the blindingly self-evident fact of its own existence; its own centrality in your reality. Sure, you're sometimes conflicted; confused -- of "two minds" about a life-altering decision -- but in your brain, all those combating feelings somehow form of a single unified whole -- a center holds amidst the flurries of memories and instincts and internal chatter. Through all of it, somehow, You are always there.

Ah, but there's the rub: You are the only one who can know that.

Here's what I mean. If you want to track down consciousness in the brain, it's actually not all that hard -- just compare brain scans of anesthetized, sleeping and vegetative patients with those of people who are awake and aware. All you need for wakeful awareness, it turns out, is a neural network between parts of the prefrontal cortex, parts of the parietal cortex, and the thalamus. That's the bare minimum; without that network, you can't be awake and aware of your environment.

Even without that network, though, the brain still feels physical pain. Even the most minimally conscious brains produce emotions. And as far as anyone can tell, there's no objective threshold where it suddenly becomes clear that this pain; these emotions; are being experienced by someone. That question can only be answered from the inside.

Oh, there are plenty of clinical tests for wakeful awareness. The CRS-R can check that you're responsive to visual cues. Failing that, fMRI scans can prove that somewhere in there, ghosts still haunt the machinery. But none of this can tell us what, if anything, it feels like to be minimally conscious -- or, for that matter, just what it is that experiences this minimal consciousness.

A growing number of scientists argue that the question doesn't make much sense - that all we're really talking about here is awareness, and awareness of awareness.

But what has become of the Self -- of that which is aware? Is it, after all, just consciousness reflecting inward -- or is it a specific, mensurate, real and quantifiable entity? Is it a ghost that can be caught?

As flawed as many scientists say that question is, it still lies at the heart of our interactions not only with vegetative patients but with each other; with animals; with infants and the unborn. Every time we crush a cockroach, or throw a homeless man some change -- every time we make the distinction between a "person" and a "thing" -- the question is always the same: "Is there someone in there?"

The neuroscientist Sebastian Seung has said that the only truly interesting problem in science is immortality. I beg to differ. The problem of Self -- of what, precisely, it is that craves immortality -- seems pretty damn interesting to me.