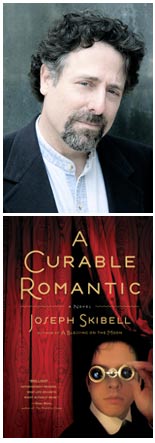

Joseph Skibell's recently released third novel, A Curable Romantic, is hard to define. On the one hand, its premise couldn't be simpler: Boy falls in love. On the other hand, it's a complex narrative that stretches from Austria in the late 19th century to the Warsaw Ghetto. Not to mention it tackles male menstruation, demonic possessions, Jewish mysticism, and the international language known as Esperanto. Oh yeah, and the book also features a cocaine sniffing Dr. Sigmund Freud.

I caught up with Joseph Skibell after a recent reading at the Margaret Mitchell House in Atlanta (where the great Southern author penned Gone with the Wind) to chat with him about his new novel.

How did you come up with the idea for A Curable Romantic?

How did you come up with the idea for A Curable Romantic?

Years ago, when I was a struggling screenwriter in Los Angeles, the thought occurred to me that it would be fun to do a screenplay about Sigmund Freud working on a case of dybbuk possession.

Let me say here that a dybbuk, according to Jewish mythology, is the soul of a dead person that refuses to submit to divine authority after death in the heavenly courts. Instead it wanders between this world and the next, pursued by a horde of punitive angels. Through God's mercy, it's allowed to shelter from these angels in three places: a rock, an animal and -- God spare us! -- in the body of another human being.

Dybbuk possession and hysteria share a number of symptoms. After I started the book, I discovered that Freud had even written an essay called "A Neurosis of Demonical Possession," in which he says that "the demonical possessions of yesteryear are just misdiagnosed cases of hysteria."

This novel covers such a variety of topics and is close to 600 pages long. At any point in the writing process did you feel that you were cutting off more than you can chew?

All through it! I really loved writing it, but in terms of complexity it was beyond anything I'd done before. It's like a bar bet: write a novel about Sigmund Freud, Esperanto, and the Warsaw Ghetto -- oh, and throw a dybbuk into it. But the love story ties everything together.

All of your books have some Jewish component to them. Why does religion play such an important role in your writing?

Eugene O'Neill said something once about how "All the other playwrights write about man vs. man, but I write about man vs. God." And I guess that's true for me as well. As a literary motif, for me, the Jew is a figure that's not quite home in this world, and I'm interested in that tension, in the tension between a sense of absolute meaning and the day-to-day reality of life on this earth.

Any thoughts yet on what your next book will be about?

I'm working on a small book about the tales in the Talmud, and my daughter and I have written a joint travelogue about a week we spent together a year ago, visiting three guitar-makers. The book, which is almost done, is called My Father's Guitar and Other Imaginary Things: family, mortality and the end of childhood.

Benyamin Cohen is the author of My Jesus Year: A Rabbis Son Wanders the Bible Belt in Search of His Own Faith.