PISA Scores Coordinated by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development( OECD)

The headlines proclaim frightening news about American education. It has been failing for decades and is getting worse; American students are among the dumbest in the world, ranking below most industrialized nations, including Estonia and Slovenia:

HEADLINES

How America Is Falling Behind

"In the second half of the twentieth century... This tremendous stock of highly educated human capital enabled the U.S. to become the dominant economy in the world. But that lead has shrunk significantly over the past decade."

American Schools vs. the World: Expensive, Unequal, Bad at Math

"...the U.S. scores below average in math and ranks 17th among the 34 OECD [Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development] countries. It scores close to the OECD average in science and reading and ranks 21st in science and 17th in reading."

Why the World Is Smarter Than Us

"...something cultural, something nearly intangible--is holding back our school system... Academically, American schools are too easy, with surveys of students showing pervasive boredom and low expectations. Our curriculum needs a booster shot, and not just in reading and math, the two subjects covered by the new Common Core national standards, but in every area, including technical and career education."

U.S. Students Still Lag Behind Foreign Peers

A Harvard University study found: "...students in Latvia, Chile and Brazil are making gains in academics three times faster than American students, while those in Portugal, Hong Kong, Germany, Poland, Liechtenstein, Slovenia, Colombia and Lithuania are improving at twice the rate..."

Why it's better to grow up in Slovenia and Greece than the U.S

Article cites education (U.S. ranked 27th) among numerous other factors

Why Can't U.S. Students Compete With the Rest of the World?

"Yet despite the economic crisis facing the country, the U.S. educational system remains frozen in place, unable to adapt to contemporary global realities."

Pretty grim assessments of American education. But how can we reconcile those depressing headlines and news with the following ones:

Why Do So Many Chinese Students Choose U.S. Universities?

"There are more than a quarter of a million students from China in colleges in the United States ...almost a fivefold increase since 2000."

"First, there are kids who simply want the best education possible. These are super achievers who generally want to get into the top American colleges."

Chinese Flock to Elite U.S. Schools

Jay Lin from Wenzhou China came the U.S. as a teenager and earned degrees at Cornell and Columbia Universities. "Now he is helping others in China follow his path, where the desire for elite U.S. education is alive and well."

Chinese Students Coming to U.S. Middle Schools? It's Starting To Happen.

"...Susan Li, is part of a rapidly growing trend in which Chinese students are choosing to seek their education overseas as early as middle school or high school."

Why do the Chinese--with an education system that ranks at the top of almost all surveys-- send their children to the U.S. in increasing numbers for middle school, high school, and college? Why would the nation with one of the highest ratings in education want their children to attend school in the "dumbest" country with one of the "worst ratings" in education?

Then there are these laudatory headlines?

U.S. Remains the Dominant Leader in Science and Technology Worldwide

"Much of the concern about the United States losing its edge as the world's leader in science and technology appears to be unfounded."

U.S. Positioned as Technology Export Leader for Next 20 Years

"Technology-intensive goods are expected to account for 17% of the total growth in U.S. export goods for the rest of this decade, HSBC stated."

Reports that the United States ranks first in Bloomberg's Global Innovation Index.

American Leadership in Science, Measured in Nobel Prizes

"The United States has won more Nobel prizes for physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, and economics since World War II than any other country, by a wide margin."

Headlines that affirm American educational leadership tell a strikingly different story. So which is it: damnation or cheers for American education? It can't be both--or can it?

Is the key to the discrepancy number three of the three kinds of lies: Lies, damned lies, and statistics?

Most measures comparing educational systems and students of countries cite mean (average) scores. The mean is a commonly used measure for comparisons, but it can be misleading. To calculate the mean just add up all the scores and divide by the number of subjects.

For example, If the total score for a group of 20 students on a science test adds up to 1600 we would divide 1600 by 20 and come up with the average score of 80. So what could possibly be wrong or deceptive about the mean?

A graphic example will clarify:

Tom Thumb measured 3 feet 4 inches. Former basketball player Shaquille O'Neal is 7 feet 1 inch tall. On average, they are 5 feet 2 inches, which tells nothing about either of them. In a group of 2,000 Tom Thumbs and 2,000 Shaquille O'Neals, the mean or average height for the entire group would still be 5 feet 2 inches and would still reveal nothing about any of the four thousand subjects.

This improbable example shows how the mean or average is not useful when the members of a group fall into extremes. Savvy readers of statistics will, therefore, look beyond the average to ask about the range and concentration of measurements within a sample.

A measure known as the standard deviation tells more about the distribution of scores. Sixty eight percent of all scores of a sample fall between one standard deviation below and one standard deviation above the mean. When that encompasses a large range of scores, as in the height example, it would be a tipoff that the mean measure was misleading, while a small standard deviation would suggest that the mean more reasonably represented the population as a whole.

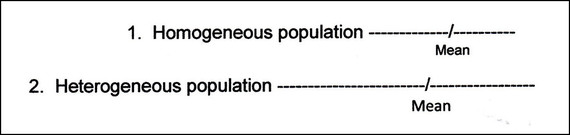

Let's now apply this analysis to comparisons of mean scores in education. Unlike the example of Tom Thumb and Shaquille O'Neal, there are many countries with relatively homogeneous populations, where all the scores fall into a relatively narrow range with most scores bunched in the middle. That sample would produce a higher mean than a diverse multicultural population like in the US with a wide range of scores including extreme lows and extreme highs with more extreme lows than extreme highs--a pattern that would produce a lower average score than the homogeneous population. What is lost in looking just at the mean is that the population with the lower mean had significantly more extreme high scores than the population with the higher mean, as can be clearly seen in the illustration below:

The population in example 2 has a lower mean or average score but has more higher scores than the population in example 1 with the higher mean. Let's say that a significant number of higher scores in example 2 that are higher than the highest ones in sample 1 consisted of ten percent of the sample 2 population. Well, that's all that may be necessary for the country of sample 2 to be the leader in technology, innovation, and more. And that is precisely why the "dumbest" country (the U.S.) can be the leader in the world and why some of the "smartest" countries in the world have contributed little to innovations in the twenty-first century.

Also keep in mind that sampling in heterogeneous populations is challenging for adequately including the full range of abilities and performances of the extreme diversity within the population.

The above example also suggests how focus on the mean can lead to faulty conclusions about solutions for improving education that mask the real problems. The U.S. may have a lower mean score than other countries on various education measures, but it does not have a problem at the top or even in the middle, as just illustrated. It's the bottom end of education that needs attention and improvement.

And much of the needed improvement is not necessarily in education per se but rather in attention to issues like poverty, unemployment, social disorganization, drugs, and discrimination. Indicting American education as a whole based on mean scores would be like concluding from the Tom Thumb/Shaquille O'Neal average height that we need an emergency program to address why the height of that population is lower than the average height for the rest of the world. And others might scratch their heads wondering why that population with such a low average height had the greatest basketball teams in the world.

This analysis is supported by the finding that on the OECD measures: "Average scores from Massachusetts were above the international average in all three subject areas" and "Florida students on average scored below the international average in math and science and around the international average in reading." Further exposing the flaw in the reports of mean scores of students internationally is that Israel, a world leader in science and technology, shows mean scores on reading, math, and science even lower than the U.S. Like the U.S., though, Israel has a highly diverse population, including a constant inflow of immigrants with language, adjustment, and economic issues, which nationally generates extreme high scores and extreme low scores.

Perhaps politicians in the U.S. who oppose increased funding for education--even lowering support and decimating education with proposals like eliminating the Department of Education-- have figured out that all America needs to be the innovation leader of the world is its upper ten percent of the population, and, therefore, to hell with the rest of its citizens.

Compare the upper ten percent of American students with the upper ten percent of all the countries that reportedly are beating us and the rankings and conversation will take a dramatic turn.

Then we might attend to the real problems of American education.

Bernard Starr, PhD, is Professor Emeritus at the City University of N.Y., Brooklyn College, where he taught educational and developmental psychology in the School of Education. He is also the main United Nations representative for the Institute of Global Education (IGE) that founded the Mucherla Global School in Mucherla India. IGE s an NGO with consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations.(ECOSOC).