A new class of "climate fiction" has hit the publishing scene. But is it the real deal or just a flight of fancy?

Climate Fiction: An Official Genre?

There's an unofficial new genre called climate fiction, or more familiarly, cli-fi. Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow, writing in the magazine Dissent: A Quarterly Journal of Politics and Culture this summer, proclaimed "Cli-Fi: Birth of a Genre." By some accounts, the term was coined by Dan Bloom in 2007 "as a subgenre of science fiction." Since then, and much to Bloom's delight and chagrin, "both NPR and The Christian Science Monitor did major stories about 'cli-fi' as a new literary term ... [and never] mentioned [his] role in coining the term."

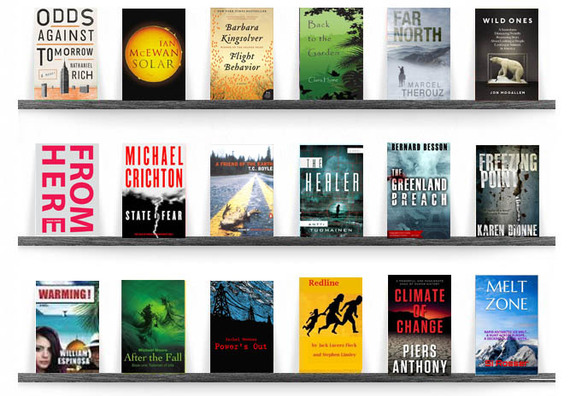

Since first appearing in print in 2010, and without me and I suspect many of you noticing, the term "cli-fi" has reached marketable status. Plugging the search term into Amazon, I got an impressive 202 hits. Many of them turned out to have nothing to do with climate or even fiction (e.g., some dictionaries were among the returns). Still, quite a number were novels that feature climate change as a major theme and driver of the plot.

Even Margaret Atwood, one of the great writers of our time, has given cli-fi her stamp of approval:

"There's a new term, cli-fi (for climate fiction, a play on sci-fi), that's being used to describe books in which an altered climate is part of the plot. Dystopic novels used to concentrate only on hideous political regimes, as in George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Now, however, they're more likely to take place in a challenging landscape that no longer resembles the hospitable planet we've taken for granted."

Does Dystopian Fiction Inform the Climate Change Discussion?

I think it's great that climate change has gotten the attention of writers and that their work is garnering attention in the media and the marketplace. But I am also a bit disappointed: It seems the primary theme of books that are being recognized under the rubric of "climate fiction" are essentially dystopian visions of a world decimated by climate change.

Dystopian fiction is nothing new; it's been around long before global warming became a household term. I remember as a teenager cutting my post-apocalyptic reading teeth on Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, published in 1932. And if you're looking for contemporary dystopia I can think of few better than the above-mentioned Margaret Atwood, some of whose novels have been categorized as "cli-fi."

Dystopian fiction is, obviously, the opposite of utopian fiction. While books about utopias feature perfect, wonderful places, dystopian fiction, according to TheFreeDictionary.com, is "a work ... describing an imaginary place where life is extremely bad because of deprivation or oppression or terror." At its most basic level, the plot goes something like this: Some kind of really bad or apocalyptic event or events happen that profoundly undermine the social order and humanity is left to cope in this new world. The cause of the apocalypse can vary; it might be political oppression as in George Orwell's 1984, Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 and Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, or corporate tyranny as in Fritz Lang's Metropolis, or a nuclear holocaust as in Nevil Shute's On the Beach, or extreme fuel shortage in George Miller's Mad Max, or a killer virus as in Terry Gilliam's Twelve Monkeys.

The thing that makes dystopian fiction so intriguing, at least to me, is not the cause of the apocalypse and not that it might serve as a rallying call to action to avoid the apocalypse. Rather, it is the social science aspect -- the author's vision of how humanity chooses to organize and cope in the post-apocalyptic world. In good dystopian fiction, the cause of the apocalypse is merely the vehicle to get us to the post-apocalyptic world and a vision of a new world order.

And so I don't see the dystopian cli-fi literature as all that much of a game-changer for the climate change debate, and perhaps even a bit of an exploitation of the issue -- a handy and timely plot element to get the story going. I'm not saying it's not good literature; I'm just questioning its relevance to the very real issues we face as a society today in trying to decide how to respond to climate change.

A Cli-Fi Novel That Stands Apart: Flight Behavior Makes Climate Change Tangible.

For a novel that I find takes those issues head on and makes them personal and tangible, check out Barbara Kingsolver's 2012 novel Flight Behavior. In an NPR interview Kingsolver described why she chose to write Flight Behavior:

"Why do we believe or disbelieve the evidence we see for climate change? ... I really wanted to look into how we make those choices and how it’s possible to begin a conversation across some of these divides ... between scientists and nonscientists, between rural and urban, between progressive and conservative."

Kingsolver places her novel in rural Tennessee among farmers and other blue-collar types who would find the usual tips many of us bandy about for "going green" -- flying less or buying a Prius -- laughable. Not because they don't care about the environment but because such actions are irrelevant to their lives -- they've never and probably will never take an airplane because they can't afford to and the only vehicle they drive is the old pick-up that's been around for decades.

The author takes these people and makes them confront an ominous and, for many, seemingly miraculous event -- the arrival of millions of monarch butterflies to the mountains of Appalachia. It's an event almost certainly caused by climate change and one that brings good things and bad things to the community, it divides them and profoundly challenges their beliefs, assumptions, and lifestyles. The way the characters choose to respond to these challenges in their varied and individual ways provides in a microcosm the challenges our society faces in developing a consensus on a suitable response to a very real and disturbing threat. And importantly, does so without transporting us to an imaginary, post-apocalyptic world but by making us, like the people in Kingsolver's rural Tennessee town, confront our changing world and the people that populate it.

It's a great read. If you haven't yet settled on your holiday reading list, you might want to put this one on it.

Written as part of our Artful Planet series in partnership with

the University of Washington's Conservation Magazine.