My first year at summer camp, I heard rumors about the Saturday evening campfire. Something strange happened afterwards, I'd heard, but no one would give me the details.

At dusk on that first Saturday, I congregated with the rest of the camp for the quarter-mile hike to the campfire site. No flashlights were allowed, and the instructors advised us to look behind as we walked through the woods. Anticipation mounted.

At 10:30 PM, as the evening's talent show ended and the bonfire coals flickered into darkness, I finally learned the Great Secret. Each of the first-time campers was going to walk back to camp, through the wilderness, in the pitch black, alone. I quaked in my poorly tied boots.

Years later, as a returning camper and instructor, I would come to relish the memory of my first "night walk," a rite of passage that no one tells you about until it's upon you.

But at that moment, as I waited for my turn to descend the ominous granite shelf, my mind erupted with fear, anxiety, and the litigious thoughts of an entitled 11-year-old. This is ridiculous! Who do they think they are? I'll sue everyone!

A hand fell on my shoulder. "Don't freak out," an instructor gently advised me. "We've been preparing you for this."

She was, I realized, correct.

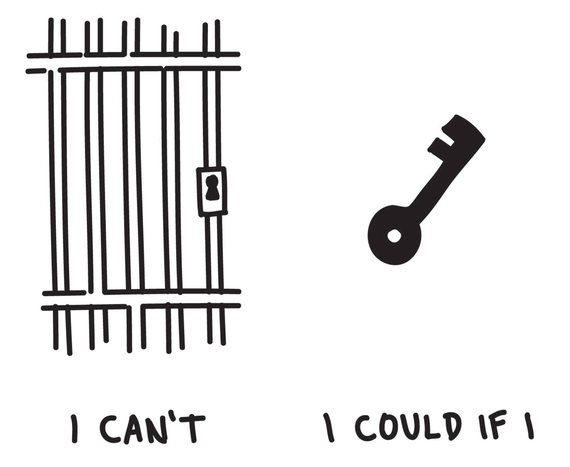

Deer Crossing Camp was a strange and special place to grow up each summer, and not just because they asked 11-year-olds to walk through the woods alone. The very first thing you learned at Deer Crossing was that at this camp, you're not allowed to say "I can't." Not during classes, not during meals, and not even during casual conversation.

Sure, I remember thinking when I heard the rule on the first day, like that's going to happen. It sounded like the type of grand pronouncement that a school principal would blurt on the first day of school and never really enforce.

But then I arrived at camp and saw that everyone actually took this rule seriously.

The rule wasn't universally followed, of course, and the most serious consequence for saying "I can't" was the jeers of your fellow campers crooning in unison, "You whaaaat?"

But this strange policy completely succeeded in one respect. At Deer Crossing, you learned that every time you said "I can't," you were making a choice. Because instead of saying "I can't," the instructors gently reminded time and time again, we could say a different phrase: "I could if I."

My first "I could if I" moment was in kayaking class when we practiced flipping our boats over and escaping from them into the water. (These were whitewater-style closed-top kayaks, not open-top ones.)

During one of my flips my foot became stuck, forcing me to swallow a mouthful of water, panic, and get mad. "I can't do this stupid kayaking!" I protested. I was prepared to walk away right there, but my instructor convinced me to ask myself "I could if I" first.

What had caused my foot to stick in the kayak, and what could I do differently next time? I reluctantly began brainstorming.

"I could get my foot out if I . . . wore smaller shoes."

"Yes, that's one option," the instructor replied. "What's another?"

"If I bent forward more?"

"Okay. How about one more?"

I racked my brain. "If I . . . took a deeper breath to give myself more time?"

"Great. Let's try that one."

Lo and behold, on the next flip, I exited the kayak like a slippery fish.

* * *

If someone had introduced the "I could if I" strategy to me as an adult, I may have written it off as self-help hogwash. But to my 11-year-old self, facing the prospect of a terrifying night walk, "I could if I" was the key that unlocked my cage of self-doubt.

As my knees quivered in that cold mountain night, I took a deep breath, recomposed myself, and asked myself, "I could do this walk if I . . .

walked down to the edge of the granite shelf, where the dirt begins . . .

walked between the two tall trees . . .

and followed the rocky gully down to the forest trail.

I took the first step. Five minutes later, I was back at camp.

Summer camp taught me that my habit of saying "I can't" was a cage, and this cage had a key called "I could if I." To escape the cage, all I had to do was pick up the key and think a little differently.

Attitude is a self-directed learner's most precious resource. For every cage, you can find a key.

More Cages and Keys:

I can't --> I could if I

I should --> I choose to

I don't know --> I'll find out

I wish --> I'll make a plan

I hate --> I prefer

I have to --> I get to

This is an excerpt from The Art of Self-Directed Learning by Blake Boles. The original chapter is titled "Cages and Keys". Illustration by Shona Warwick-Smith.

Download the audiobook for free by joining Blake's author mailing list.

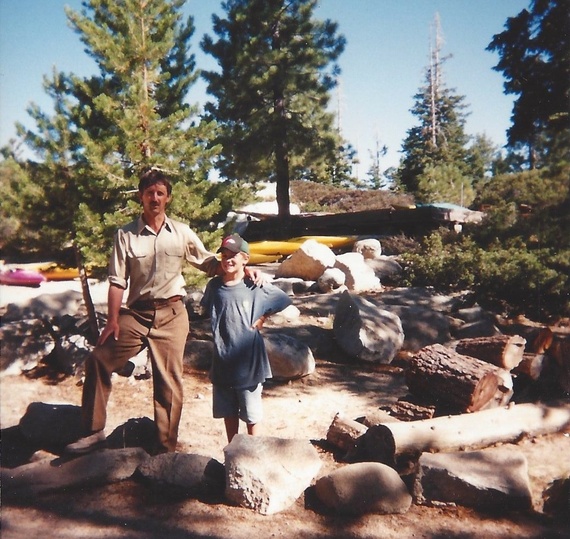

Blake, age 11, at Deer Crossing Camp with camp director Jim Wiltens

Blake, age 11, at Deer Crossing Camp with camp director Jim Wiltens