My post today might seem of primarily local interest in San Francisco. But if you give it a look, you will see that it deals with issues of human rights, social activism, and community ideals that should be of interest to a wide readership. -- Bob Ostertag

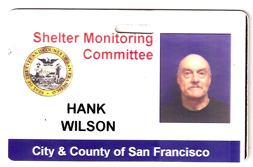

Hank Wilson

April 29, 1947 - November 9, 2008

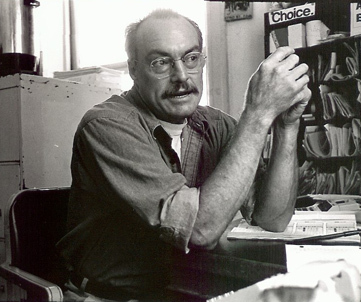

Hank was not only the most selfless person I ever met, but that I can even imagine. Not for one moment was Hank the topic of concern in his own life. I would like for people who did not have the privilege of knowing him to know of him.

- Bernice Becker, Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG).

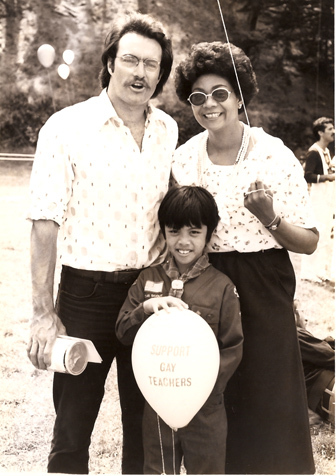

Sacramento native Hank Wilson arrived in San Francisco just a few years after Stonewall in the early 1970s, a young gay man in his early twenties. He got a job teaching kindergarten, and dove into political activism. Together with Tom Ammiano, who was teaching English as second language, they spearheaded the Gay Teachers Coalition (GTC), which became the focal point of the campaigns against Anita Bryant and then against the Briggs Initiative. Bryant was the pitchmeister for the Florida Citrus Commission, but best known as the first Christian homophobe with national projection, leading anti-gay legislative efforts around the country, culminating in the Briggs Initiative in California, her first and decisive defeat. These were the formative political battles of the post-Stonewall gay and lesbian community in San Francisco, and they were the battles that launched Harvey Milk and Tom Ammiano's political careers. Hank, however, was not interested in a political career.

The number of organizations that Hank was involved in founding that are now the pillar organizations of the gay and lesbian community both in San Francisco and nationally is staggering. He was a sort of Johnny Appleseed of gay and lesbian organizing: wherever he went organizations sprouted:

•Gay Teachers Coalition, later renamed the Gay Teachers and School Workers Coalition.

•Bay Area Gay Liberation (BAGL), the Bay area's "gay liberation" group of the 1970s.

•Lavender Youth Recreation and Information Center (LYRIC) This remains the main organization for queer youth in San Francisco. It came out of Gay Youth Advocacy Council on which Hank served.

•With Ammiano, Hank launched a gay speakers bureau to educate San Francisco high school and middle school students about gay and lesbian issues.

•Served on the San Francisco Human Rights Commission's Youth and Education Committee.

•Butterfly Brigade.

•Castro Street Safety Patrol.

•The Carry a Whistle Defense Campaign. (For those of you queers out there who carry whistles in your pockets in case of gay bashing, those whistles can be traced back to Hank.)

(Many of the activities of the speakers bureau, the Butterfly Brigade, the Castro Street Safety Patrol and the Carry a Whistle Defense Campaign have now been subsumed in the organization Communities United Against Violence (CUAV)).

•Frameline and the SF Gay and Lesbian Film Festival. (Hank: "We did the first one with sheets tacked to the wall with push-pins. We didn't have much to show. But everyone was so excited just to see ourselves on a screen.")

•ACTUP.

•Survive AIDS.

•The AIDS Candlelight Vigil

•Tenderloin AIDS Resource Center (TARC).

•The Valencia Rose. A gay and lesbian cabaret very influential in San Francisco culture. Yes, in the middle of all that, somehow Hank found time to run a cabaret.

Along with all the organizations he had a hand in founding were many more that benefited from his participation very early on, including Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) and many more. Almost any one of these could have become a base for launching a career in politics in San Francisco and beyond. But Hank's idea was that as soon as something was up and running, he would move on to start something else. Very few people ever had a full picutre of how much he was involved in.

Tom Ammiano's 1999 mayoral campaign is a case in point. Ammiano was by then on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Though he was recognized as the voice of the gay and lesbian community in city affairs, Hank's long-time ally was considered too flamboyant and effeminate - too gay - to have a political future on a bigger scale. But suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, Ammiano appeared with a last-minute write-in campaign that nearly unseated Mayor Willie Brown, one of the most powerful political figures in California. Though Ammiano lost the run-off he forced on Brown, the campaign is considered an historic turning point in San Francisco politics, galvanizing progressive voters and leading to a major progressive turn in the Board of Supervisors elections the following year. What is almost completely unknown is the genesis of Ammiano's late-entry write-in campaign. It started when Hank, all by himself, went to the Folsom Street Fair with a poster of Tom and a petition Hank had drawn up for collecting signatures asking Tom to run for mayor. By the end of the day, there was a de facto Ammiano write-in campaign. Hank had not told Tom he was going to do this. And once the campaign was underway, Hank did not get a powerful position in it.

This is a perfect example of what Hank did all his life: lead by doing. Don't call a meeting, don't have a big argument, don't read up on Robert's Rules of Order. Just dive in and start doing the right thing. Then, when you have attracted a critical mass of support, let go of the reins and look for something else to do. "Here is a mayoral campaign for you Tom. Have fun."

Bernice Becker, one of the earliest PFLAG parents, says, "As the years go by people go off in different directions, but he never did. Tom of course went into politics. Which is not to criticize. Far from it. But Hank was different." Soon after the formation of PFLAG Bernice's gay son took his own life. Thirty years later Hank was still making grocery runs for Bernice, now 87 and suffering from two broken hips, even as Hank's own health declined. "He was already unable to swallow and coughing up blood, but he didn't tell anybody. He would carry the groceries up the stairs behind me so I couldn't see him struggle. Finally I said, 'Hank, now you have to tell me something I can do for you.' He said, "I'll think about it.'"

Hank's main commitment was always to those at the very bottom, the truly down and out. In the mid-70s his friend Ron Lanza was looking through the classified ads for a job and found a listing for a hotel manager. It turned out to be an SRO hotel in the Tenderloin, San Francisco's skid row. Ron was dubious. The pay was very low and it seemed like a lot of stressful work. He asked Hank for advice. Hank told him to tell the employer that Hank was Ron's lover. Why? "That way they'll think they are getting 2-for-1," said Hank. Hank never needed much money, was not really even concerned about money. But managing a residential hotel for poor people intrigued him. Hank and Ron ran the hotel, and then another bigger one, and then another. Eventually Ron dropped out of the hotel scene to open the Valencia Rose cabaret. Hank somehow found the time to be Ron's partner in the Valencia Rose while escalating his hotel work at the same time. Soon Hank was manager of the Ambassador Hotel, a 150-room SRO hotel in the heart of the Tenderloin. Hank took over the Ambassador in 1978, just before the AIDS epidemic hit. Soon the Ambassador was filled with formerly homeless people dying of AIDS.

To tell the whole story of Hank and the Ambassador Hotel would require a book. Hopefully, this book will be written sometime. Hank was running the hotel in the Tenderloin with an all-queer staff: drag queens, pre-op and post-op transsexuals, dykes and fags, queers of all colors. As AIDS began to fill the hotel, somehow Hank connected with a nurse who, during his off hours from his full-time nursing job, would come to the Ambassador and provide nursing to scores of dying people, working out of the trunk of his car. Little by little, a crew of extraordinary nurses, social workers, counselors, and so on, congregated at the Ambassador. Together they pioneered numerous innovations in homeless services that eventually seeped upwards and changed the way San Francisco deals with homelessness - though not nearly as much as we would like. As Tom Calvanese, who worked under Hank at the Ambassador for seven years, puts it, "We were attracted by this innovative model of care that was emerging. but mostly we were attracted by this force of nature in the middle of it all named Hank Wilson."

Incredibly, Hank and his tribe were doing this without any public funding. Somehow they made the rent they collected on the rooms pay for everything, including the rent they themselves had to pay to the slumlord scumbag who owned the building, which escalated sharply during this period. Hank and company were providing homeless services beyond what the city agencies were providing, without a penny of public money, paid for by the meager resources of the clients themselves. This was not supposed to be possible.

The term "harm reduction" did not enter the American medical lexicon until the late 1980s. By then Hank and company had run a comprehensive one-stop-shop harm reduction facility for ten years, without expert advice, professional staff, or even any funding.

Eventually one entire floor of the hotel was set up as a hospice for those dying of AIDS. It was the floor with Hank's office.

KRON, the local NBC TV affiliate, got wind of it all and wanted to film a documentary about Hank with the title "Mr. Ambassador Hotel," which by this time was the nickname people in the Tenderloin used for him. Of course, Hank would have none of it. The doc was eventually made and aired under the title "Life and Death at the Ambassador Hotel." Hank makes just one very brief appearance in the film, when he arrives at work in the midst of the chaos, and walks through the camera frame, obviously annoyed to be on camera, saying something like, "OK, The lights are on, the water is on, the heat is on, check check check," before waving the camera off and scurrying away to deal with some emergency or other.

Hank ran the Ambassador for 18 years, from 1978 to 1996. Tom Calvanese worked with him for seven of them. Tom: "I did it for seven years and that seemed like a long time. A really long time. Hank did it for 18. I would be like: what is wrong with you?!?" Hank only stopped when both his mother and father were in their own dying process. Hank left the Ambassador to care for his own parents.

After his parents died Hank resumed his work with the homeless, this time at the Tenderloin AIDS Resource Center, yet another organization he was involved in founding. But he had had enough of being the boss. Tom Calvanese, his employee at the Ambassador, took over as boss so Hank could work closer to the ground, where he preferred to be. He started TARC's free breakfast program. Hank: "You can't educate anyone about AIDS when they are hungry." Hundreds of free breakfasts a day were served with only one paid staff person (Hank) and a crew of volunteers, all homeless themselves.

Tom told me what it was like being Hank's boss, how he constantly had to run interference for Hank. "The way Hank does things would flip everyone out. 'He violates all the rules!' 'He has no boundaries!' 'He has no boundaries!' 'We must call a meeting!!'" And over and over Tom would say, "So, what you are saying is that Hank drove someone to the hospital that he shouldn't have? This is what you want to have a meeting about? This is what you think we should spend our time on? Do you realize that I am the boss, and I trust Hank's judgment more than I trust my own?"

Remember, ACTUP, LYRIC, and all of that community activism - Hank did all that in addition to running the Ambassador. And on top of all of that, Hank had AIDS himself. Bad AIDS. Terrible Kaposi's Sarcoma (KS). Lesions all over his body and eventually on his face. Tuberculosis. And finally AIDS-related dementia. Protease inhibitors came along just in the nick of time to pull his one foot out of the grave and give him back his health.

Hank's last big battle was over the marketing and use of poppers by gay men. Poppers are a chemical substance some men inhale as a stimulant during sex. They are very bad for you. The actual mix of what is in "poppers" has changed over the years as the makers tried to skirt successive legal restrictions, but the medical consequences have stayed the same. In the early days of the AIDS epidemic, before HIV had been isolated, many speculated that AIDS was the result of the use of this clearly toxic chemical. With the discovery of HIV, the focus on poppers died out. For everyone, that is, except for Hank. Hank was around a lot of men with AIDS, and he noticed that disease progression seemed more rapid among men who did poppers. After the introduction of effective anti-HIV therapy in the late 1990s, he noticed that the only men he saw who continued to contract Kaposi's Sarcoma (KS) used poppers.

AIDS professionals did not want to hear about this. A highly vocal minority of "AIDS denialists" had emerged who insisted, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that HIV did not lead to AIDS, and that poppers and other gay male sexual practices were the real culprit. AIDS bureaucracy leaders felt that any discussion of poppers would play into the hands of the AIDS denialists.

This was just the sort of thing that would drive Hank nuts. The idea that gay men had to be coddled by the medical establishment because they somehow would not be able to grasp that HIV caused AIDS and that poppers were bad for you infuriated him. "The gay community can learn how to walk and chew gum at the same time," he would say. So Hank became a one-man anti-poppers movement. He discovered that most poppers were made by one company out East, owned by a man with mafia connections who bought political cover for his illegal poppers enterprise by making fat donations to Bill Clinton's foundation and other gay-related philanthropy. Hank started hounding the guy, his company, the people who sell poppers locally, and the authorities who should have been enforcing the law against the sale of poppers but are not. It got to the point that Hank put all his research material in a safe box and told his closest friends that if his body was found in a ditch someday to point the police toward the popper man.

But for once, Hank had done the right thing and, despite sticking with it for a long time, no one appeared to join him. Hank had no problem with that. Being the only AIDS activist in America pushing the poppers issue did not bother him in the least. Just a few months before he died, a major epidemiological study was published that indicated, to the surprise of the studies' authors, that popper use among gay men correlated more strongly with new HIV infection than crystal meth use. Hank was thrilled. Since the gay community expends huge resources combating meth use, he reasoned, the same would now have to be done for poppers. Unfortunately, this has not happened. Instead, Hank engaged in a battle with the study's authors just to get them to make the results public (which has also not happened yet). Hank's "Committee to Monitor the Use of Poppers," which he had founded 27 years ago, remained until his death a committee of one. Today it is a committee of none.

Through it all Hank lived on next to nothing. He had the same apartment for 30 years, a tiny one-room studio on the outskirts of the Tenderloin. There was no bed. He slept on a thin mat he would roll out on the floor. After the feeding tube was inserted in his stomach at the hospital a couple of weeks ago, he made arrangements to go home to die. His closest friends finally convinced him that if he was going to die at home in his own bed, he ought to actually have a bed. "But I don't want to spend a lot of money!" Later, when he was back in the hospital, just a couple of days before he died, he asked the nurses if he could return home. Would there be anyone there to care for him, they wanted to know? "The roaches," he whispered in between the blood he was coughing up.

Many times I tried to get Hank to go kayaking with me, but that was far too much energy to spend on his own enjoyment for Hank. His one release valve was going to the Russian River, a popular gay resort an hour north of San Francisco. Lots of gay hotels, gay B & B's, and so forth. But when Hank would go to the River he would sleep in his car.

Contrary to what one might expect from someone who spent his life involved in uphill struggles on behalf of the destitute and drug addicted, Hank was not a grim person in the least. In fact, for those that knew him, he was known mostly for his sunny disposition. Hank was always upbeat, always smiling, and most of all, always finding the humor in everything. Even in the most dire circumstances, Hank's sunny side never seemed contrived. Even more than his drive, his astute politics, or his ability to find the good in people everyone else had written off, it was the radiance of Hank's sense of humor that was at the root of his quiet charisma. No matter what he was doing, he was usually having fun, and this drew people to him.

The way Hank put it, everyone "has pluses and minuses." From the mayor right on down to the addict in the gutter. Hank wasn't interested in the sum total of pluses and minuses. "The question is: "what is the trend?' Which are on the increase, the pluses or the minuses? Is there a way to get some momentum on the plus side?"

Nothing is more indicative of who Hank was than the way he told me he had been diagnosed with lung cancer (he never smoked a cigarette in his life, nor did he smoke pot.) I called him up one day all in a tizzy over something, I cannot even remember what. Hank was always the best person to call when you were in a tizzy because he always genuinely listened. Anyway, I went on and on about whatever my problem of the day was, and after 10 or 15 minutes I finally asked, "So how are you?"

Hank: "Oh, I'm fine. Really, I'm fine. I mean, I was diagnosed with lung cancer a few days ago, but I'm fine. I spent the last few days in the library reading up on lung cancer. And every day I learn more, I feel better. And what I have learned is this: the interesting thing about lung cancer is that it kills more people than any other kind of cancer but there is no activism around it because people think that because they smoke they don't have any rights. So this will be fun."

That was pure, distilled Hank Wilson: a lung cancer diagnosis was really just a new opportunity for organizing. Which would be fun. Very quickly he became one of the core lung cancer activists, though I had the impression that the others (who seemed to be ladies of considerable means) really didn't know what to make of someone like Hank.

This was Hank's life mantra: "So this will be fun."

As his health and energy declined, I remember calling him one day to see how he was.

Me: "What are you up to?"

Hank (a bit dazed): "What I am up to? I can't really remember... I have just been lying here. What have I been doing? I guess I have been dreaming... Yes, I have been dreaming. So that's fun."

Eventually his esophagus closed from the swelling of his glands. He could not swallow anything, even the saliva his mouth produced. I took him to the hospital where they inserted a tube into his stomach to pour nutrients in to directly.

Hank: "I'm fine. Really, I'm fine. Because I can sit here and just imagine whole inventories of all my favorite foods and remember what they tasted like and go through them one by one. So that's fun."

That night he unplugged himself from all his tubes and walked down to the hospital cafeteria and bought some onion rings and chocolate cake. He chewed them for the flavor and then spit them out, facing the wall in the corner. "So I wouldn't gross anyone out. So that was fun."

Hank and I had a sexual relationship for a while but then decided our relationship was not really about sex. Nevertheless, I considered him my lover, and told him so, and he accepted that. But really, there is no name or category for the relationship we had. Hank was so independent, and so deeply private in his own way, he simply did not seem to have the sort of emotional needs that most people look to a "relationship" for fulfilling.

If there was a tragedy in all of this, it was that at the end of his life, reasonably good home hospice care was still not available in San Francisco for someone of Hank's meager income. This hit Hank and Tom Calvanese, Hank's closest ally in decades of homeless work and one of his primary caretakers at the end, hard. After 30 years of work and activism, the system was still that broken.

When Hank's throat closed he was given a suction tube to suck blood and saliva from his mouth. The tube ended in a small clear container in which the blood accumulated. The home hospice program sent a nurse who was so freaked out by the blood that she refused to approach the bed, insisting that she remain on the far side of his tiny room. Eventually Hank had to call 911 to get basic assistance, a call which yanked him out of hospice care and back into the medical industry, which was not at all what he wanted. Back at the hospital his pain-killer orders were confused, with the result that Hank had to endure more pain during his last days than was necessary, and had to mount one last battle with the health care industry just to get the pain medicine he needed. He died in the hospital, waiting for a place in a hospice which never became available for him, this man who had spent so much of his life providing hospice care for others.

But he managed to stay Hank right to the end. When I took him to the emergency room after his throat closed, he would calmly brief every new doctor or nurse on the specifics of his situation, more or less assuming that some detail on their chart would be wrong (though never in a pushy or overbearing way), and then with his eyes sparkling and a big smile he would say, "The important points to know are these: I am not into pain, I am into pleasure, and the theme of the moment is 'That's all, folks!' Ya know? Like the cartoon? 'That's all, folks!'" As I left his room he told me jovially, "I'm fine, really. I don't have any complaints... except my demise. Ha ha." He then suggested we hold "a final fundraiser selling lottery tickets" betting on the day and hour of his death. What charity should benefit from such a raffle, I asked. "Well now, that is the fun question, isn't it?" he replied.

Right to the end he continued to value his time alone. Once he shooed me out of his hospital room saying, "I know a lot of people in my situation become magnets, needing to suck in the energy of everyone around them. But that's not me. I'm fine. I can envision what a sunset and a rainbow look like. I don't need to have everything right in front of me."

The day before he died, he asked a friend if there was enough morphine left in the bottle at his apartment to end his life with. The friend answered that he had checked and there was definitely enough. Hank could barely speak, but managed to get out, "OK, and if it turns out you're wrong I'll have a sense of humor about that too." But he didn't take the morphine. He waited for the cancer to take him.

The last time I saw him he was having a communication break-down with a Russian nurse who spoke limited English. The nurse could not understand that Hank was requesting a bedside commode and as a result, he soiled his bed. Once everything was cleaned up and the nurse was gone, Hank had something to say. It took enormous effort. I had to put my ear right next to his lips to hear, and he had to repeat it three times before I got it. This was what he had to say: "If the people who do that work were adequately compensated, it would solve the financial crisis."

**

Though I am only ten years Hank's junior, Hank and I belong to different generations of gay men. The "gay and lesbian community" means very different things to each of us. For me, "gay and lesbian community" often seems like more of a marketing scam than a social reality. For Hank it was very real, in large part because he was of the generation that built it, and no one laid more bricks in that building than Hank Wilson.

What, exactly, is a "community?" At the university where I teach, there are "experts" in this matter who will give you definitions of community that use so many big words, you will need a PhD of your own just to figure out what they are talking about. Hank Wilson had a definition his kindergarten students could understand: a community was something that took care of its least privileged members. If this simple thing could not be done, then you didn't have much in the way of community. This was Hank's life project, his singular, profound contribution to the gay and lesbian community, and to the city of Saint Francis.

**

Please note: within a day or two, a Hank Wilson web site will be up, probably at HankWilson.org. If you you have memories of Hank, photos of Hank, or just want to share your thoughts on his life, please give us a visit.