For fans and collectors of 20th century African-American art, the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery has emerged as the place to go. I visited in early February, shortly after "Storm Nemo" had come to town (leaving the streets slushy and the galleries almost empty) and some two months into their inaugural show at a sprawling, new space on 100 Eleventh Ave. INsite/INchelsea was the gallery's introduction to Chelsea -- they had been on 57th Street since 1989 -- and it showcased the range and diversity of their artists. Not surprisingly, the names that stole the show were Andrews, Bearden, Delaney, Douglas, Lewis, Savage, Thomas and Thompson -- all African-American pioneers of 20th century American art.

Benny Andrews: There Must Be a Heaven, up until May 18th, begins what I hope will be a long and illustrious run of exhibits teaching the neighborhood just how pioneering these artists were. Although Andrews has become known for his later images, which were typically easier and lighter, the strength of There Must Be a Heaven lies in showing how long it took for Andrews to get to a place of peace.

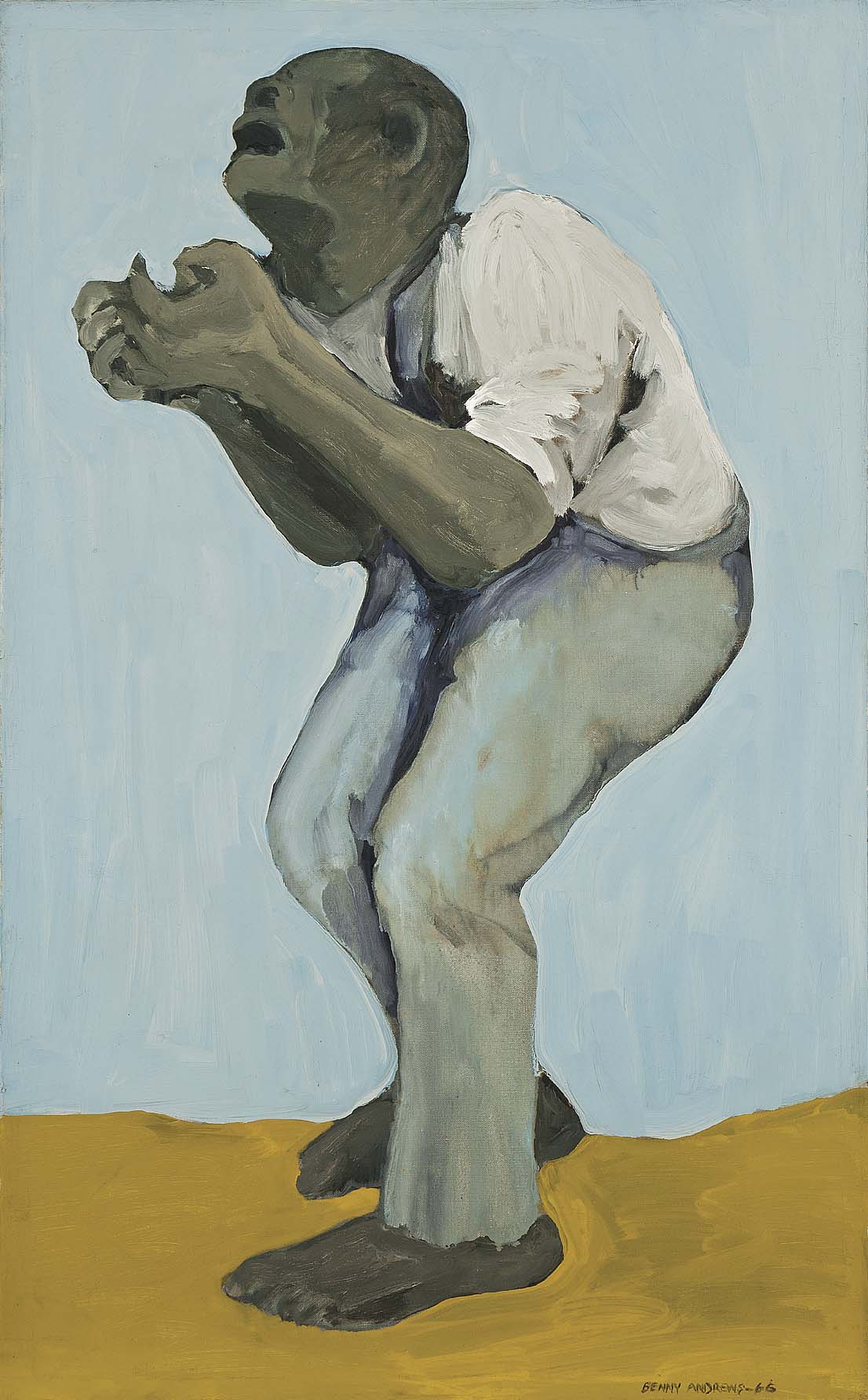

From the title work of the show, 1966's "There Must Be a Heaven" :

Benny Andrews (1930-2006): "There Must Be a Heaven," 1966. Oil on canvas, 38 x 23 1/2 inches, signed and dated. Credit Line: Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

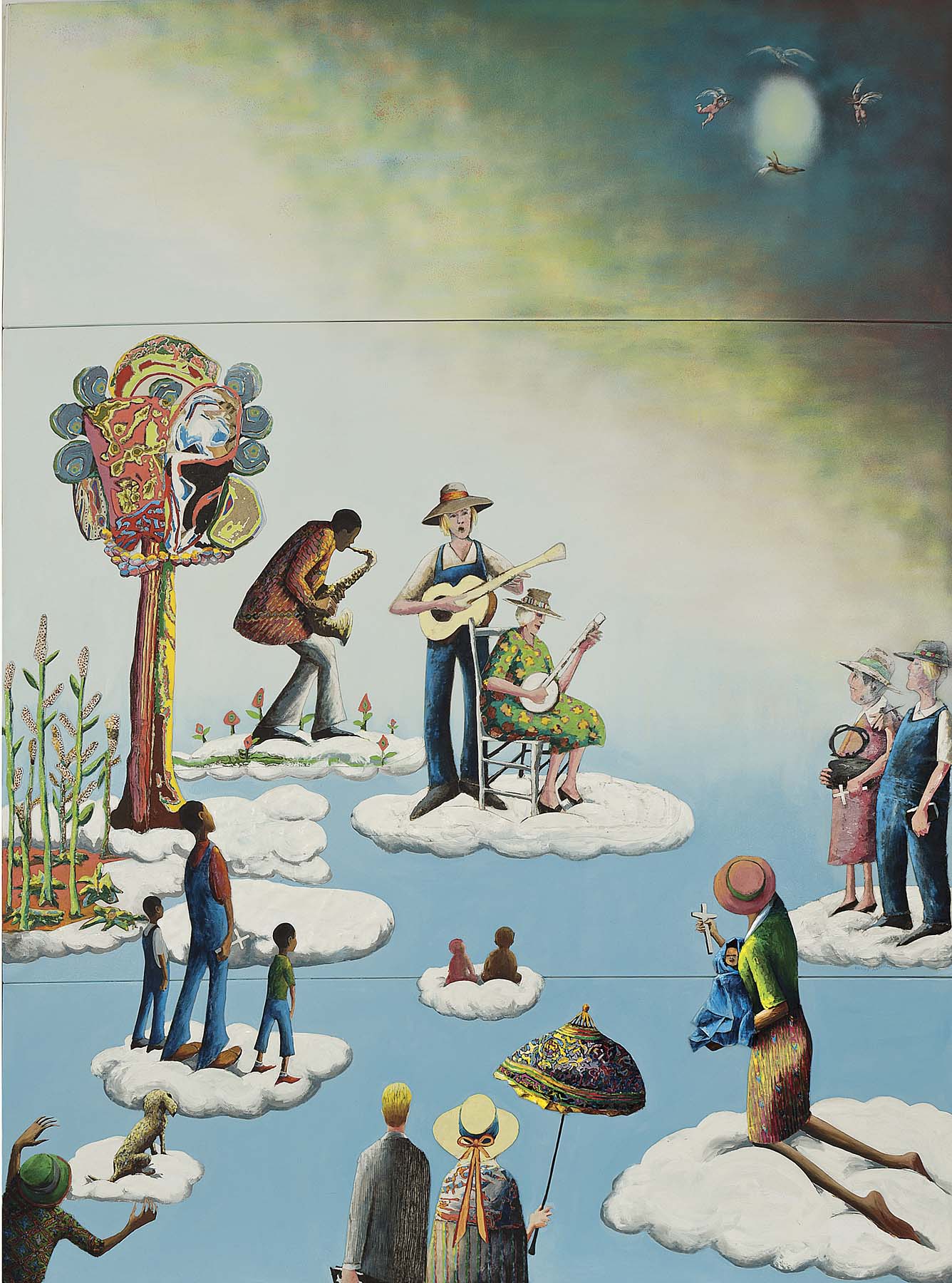

To 2000's' "Baptist Heaven," painted six years before Andrews' passing:

Benny Andrews (1930-2006): "Baptist Heaven (Human Spirit Series)," 2000. Oil on three joined canvases with painted fabric collage. 98 x 72 x 1/2 inches, signed and dated. Credit Line: Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

There Must Be a Heaven spans Andrews' entire career, showcasing some of his earliest paintings (1964's "Many Sins," 1965's "Dinner Time"), some of his last (2005's "Home Sick Blues" and "Mississippi River Bank") and everything in between. Of the 40 years covered, Andrews was a desperate, anguished painter for the first 30 of them and, to my eye, the greater painter. There Must Be a Heaven doesn't choose a side -- it does a diplomatic, gallery job of paying homage to all phases of his career -- but seeing the paintings he produced during that 30 year period, between the mid-60's and mid-90's, leaves little question as to where Andrews made his mark.

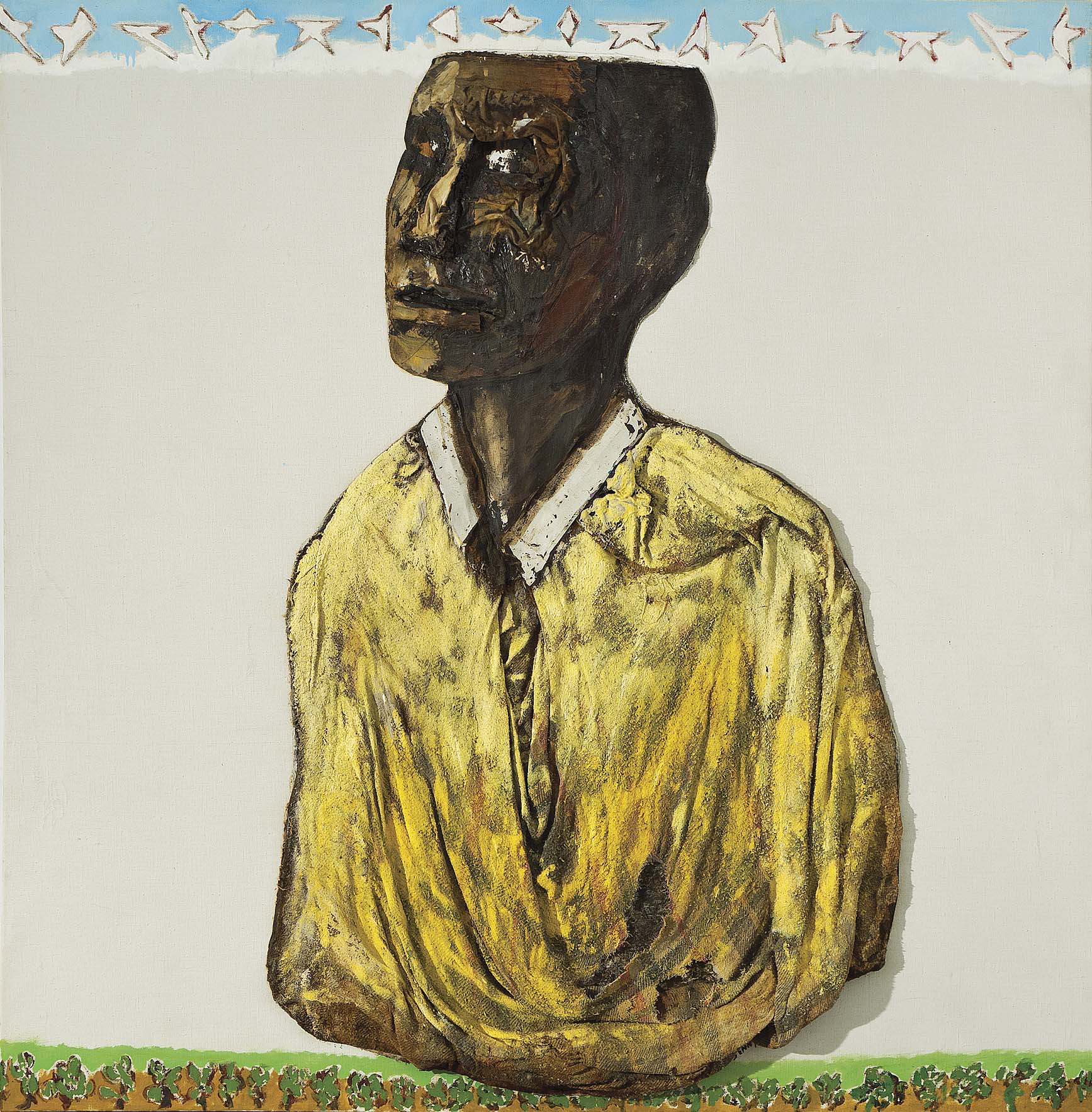

Benny Andrews (1930-2006): "A Soul," 1974. Oil on canvas with painted fabric collage. 49 3/4 x 48 3/4 x 1 1/2 inches, signed and dated. Credit Line: Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

As the Rosenfeld show illustrates pointedly, Andrews was, for most of his life, a painter consumed and driven by issues of race, inequality, poverty and war. Although it took immense bravery to follow his conscience and speak to the issues in his art, you wouldn't know it from Andrews' first major attempts. There Must Be a Heaven begins with a long wall of these initial paintings, with the artist coming across powerfully and naturally. In tone, they are not docile (1970's "Symbols Study #2" is especially chilling), but they are not simple political paintings either. "A Soul," showcasing Andrews' expressive realism, could have said more about the cotton fields at the base of the painting, but instead it focuses on the withstanding grace of its hero. The sense that Andrews was already then the painter he wanted to become -- a "people's painter" --is inescapable.

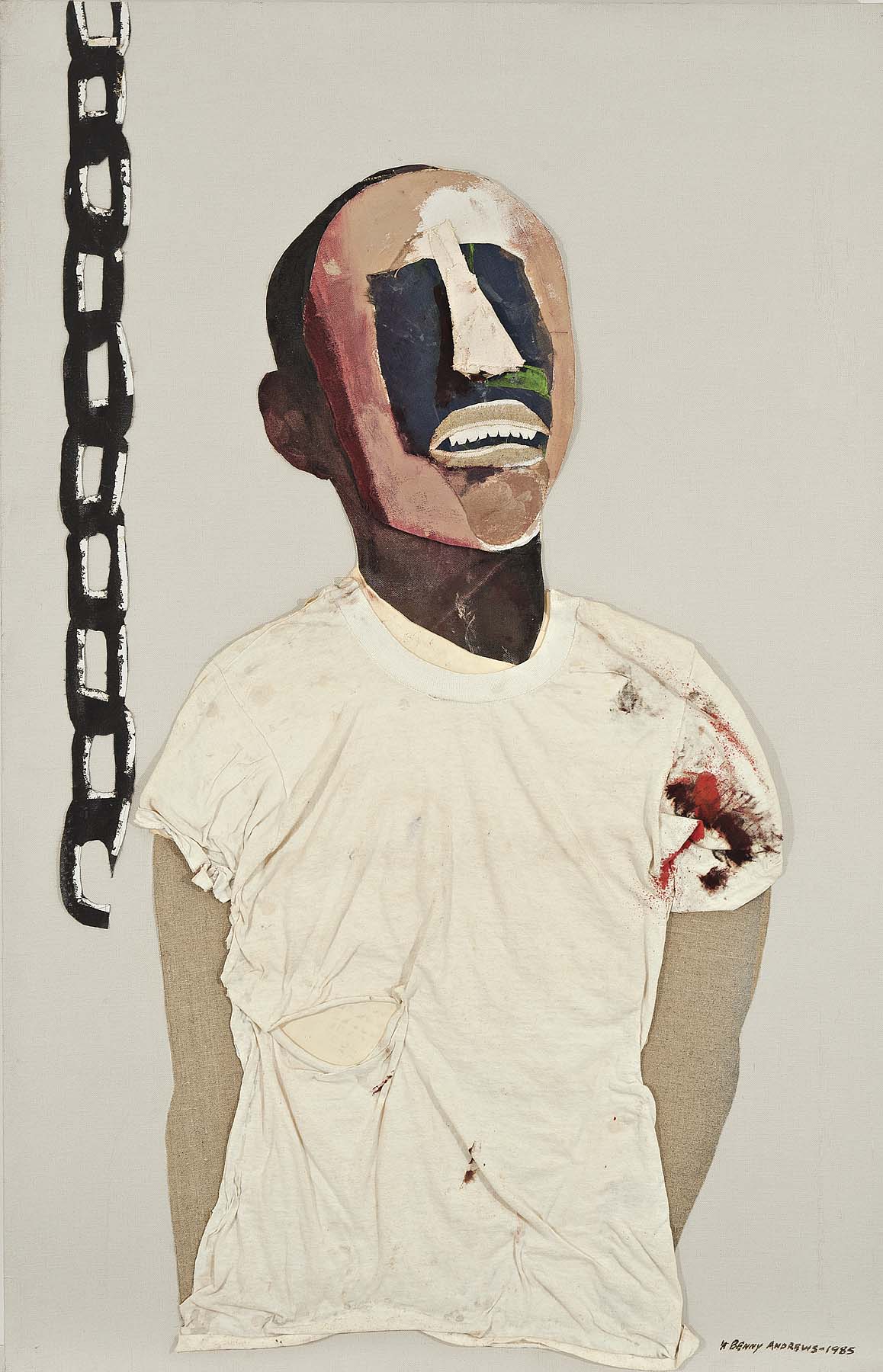

Outside of a brief period in the early '70s when his images relocated to an alternative, dream-like setting, There Must Be a Heaven tells us that Andrews stayed the course, sticking to mostly figurative scenes while developing a growing facility for collage. His concerns widened, becoming more global and historical over time, but he never ventured far from the figures of "There Must Be a Heaven" and "A Soul." Aching, many of them, they share the same unflinching quality of Faith Ringgold's "American People Series" (currently at ACA Galleries) while owing equal debt to Jacob Lawrence and his deservedly beloved history paintings. As the show's title suggests, Andrews' work was not without its hope -- hope for peace and unity one day, or at least the two in heaven -- but it was relentless in its commitment to truth and honesty. Whether confronting his southern past or Apartheid in South Africa, he continually found new reason to voice his concern and compassion for the world and for those it held captive.

Benny Andrews (1930-2006): "Study for Portrait of Oppression (Homage to Black South Africans)," 1985.Oil on canvas with painted fabric and paper collage. 43 1/2 x 28 1/8 x 1/2 inches, signed and dated. Credit Line: Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

All of this gave his paintings up until the 1990's a searing, uncompromising way. No doubt because of this and Andrews' own marginalized place as an African-American artist, they were rarely shown. Michael Rosenfeld, which represents the Andrews estate, has begun to change that with There Must Be a Heaven, filling its first room and half of its second with the paintings of Andrews' emergent and mature years, paintings I doubt I will ever tire of. They are powerful, often difficult pictures to face, Andrews at his prime -- I only wish they were part of a traveling exhibition, headed to Congress next.

The emergence of Andrews' softer side in the last decade of his career is a problem not easily reconciled in scholarship or in There Must Be a Heaven. Late in life, artists tend to loosen, producing what they want to produce and caring less of the implications. It shows in the last quarter of the Rosenfeld show. Andrews' change of course toward a more agreeable art -- both in figuration and in temperament -- happened somewhat gradually. 1996's "Confinement One," an image produced four years before "Baptist Heaven," is a noticeably more charming portrait than "Study for Portrait of Oppression," for instance, but then you realize that the man pictured is still a prisoner, his feet shackled and his pants striped. As the later works shift, they look toward music, and sometimes religion, to believe in a greater future and peace, eventually getting there with little hesitation. After a career of painting incinerate, indicting pictures, the transformation can feel a little too easy and my fear is that there are already too many people out there who have chosen the comforting arms of these late images, the preceding thirty years finally proving too hard to look at.

Of course, the images hardest to look at are the images closest to home. There Must Be a Heaven brings us home, spending most of its time in the good and difficult room of our consciences. If this show is any indication, we are in for many more, the kind the doctor and the nation ordered. Who's next? Alma Thomas would be my pick, Mr. Rosenfeld.