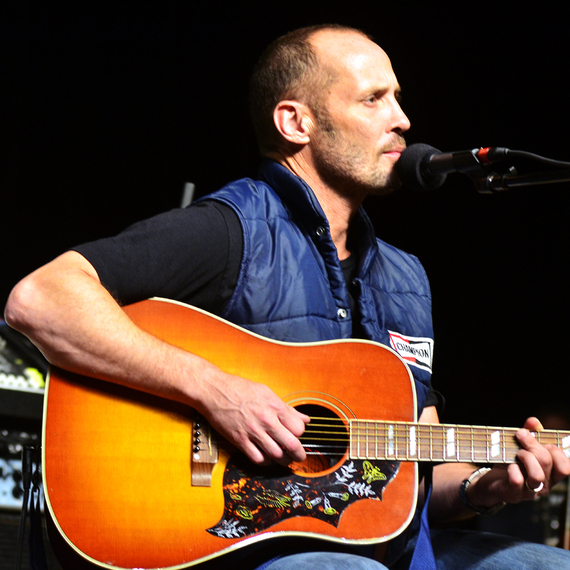

Paul Thorn's songs communicate honest humility and empathy. They tend to celebrate the singer-songwriter's own mistakes in a very comfortable and strangely euphoric manner.

There is humor and sarcasm we can all relate to. It's all trial and error and tears and a 'roll-up-the-sleeves', Pabst-drinking brand of rootsy blues music -- hard-rocking and inextricably Southern.

Son of a Pentecostal minister, Paul was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and moved to Tupelo, Mississippi at an early age after his father transferred churches. The inclusive nature of his religious upbringing left its mark.

"Of course, Tupelo is the birthplace of Elvis Presley, and growing up we attended two churches, the black people attended one, and the white people attended the other. Dad went to both churches. At the black church, I heard black gospel music, and from the white church, I learned how to play white country and western gospel music. Elvis did that same thing, he had the whole mojo."

Thorn worked in a furniture factory for 12 years, jumped out of airplanes for kicks, and he was a professional boxer before making his mark in the music world.

He released his first album, "Hammer and Nail," in 1997, simultaneously boxing as a middleweight in mostly Southern civic centers, theaters and gyms. Perhaps it's true that a certain type of personality is drawn to the boxing ring. Thorn had been chewing on the idea for years.

"There was no boxing scene in Tupelo, and I was the only guy making a serious effort at it."

Thorn's trainer was his uncle, Merle Thorn, a broad-shouldered, no-nonsense character who had sparred at the heralded Main Street Gym, in Los Angeles, with notables such as Danny "Red" Lopez and Bobby Chacon.

"He wasn't a world-beater," says Thorn, 49. "He didn't turn into a world-class fighter, but he was a great trainer. I was fascinated by him, and at first he taught me for fun. Then I had some amateur fights, I think I was 27-3 in the amateurs, and then I turned pro. I was decent. Better than poor. I never had what it took to be a world champion, I knew that."

Thorn may not have had the ingredients that made for a world-champion, but he did have the chance, as a 23-year-old club fighter, on April 14, 1988, to fight one of the legends of the sport. He cut Roberto Duran, 36 at the time, over his left eye but was bleeding so profusely himself from the sliced lip and cuts over both his eyes that Merle tossed in the towel before the bell for round seven. The fight took place in Atlantic City as the USA Network's Tuesday Night Fights main-event.

"At the time that I fought Duran, I was number nine in the NABF rankings, I believe, it was a ten rounder, I fought six rounds as hard as I could."

Thorn, sporting a 9-2-1 record, suffered a horrific cut on his lip from a right hand shot, forcing his lip to jut through his tooth and split apart.

"It was the highlight of my rinky-dinky boxing career. I was 13-2. Duran was way more talented. He was so relaxed and he believed in his own abilities, he was one of those guys who believed in themselves, without choking."

Thorn's game plan was thwarted by Duran's composure and his own lack of it. (Duran had had more than 90 bouts and several world titles to his credit.)

"My game plan went out the window. My trainer kept saying, "Don't go to him, he'll pick you apart. If you try to go to him, he'll pick you apart." I obeyed in the first, but in the second round, I was impatient and overeager. Not only was Duran a brawler, but he was a master boxer and counterpuncher. The second time, Sugar Ray Leonard figured out how to frustrate Duran. It's a great memory and I'm glad I got to do it."

Much of Duran's menace was a psychologically-driven ploy, says Thorn.

"He was a sweetheart of a guy, real accessible. He seemed to be acting it up for the stare down. Before we fought he hugged me, and when I was getting stitched up, he told me that I hurt him. I clocked him with a left hand that rattled him. He was incredibly hard to hit, but I hit him clean."

Thorn's career in music has been more durable and impressive than his one in boxing.

Culture is a mass system of commerce that runs so strong in society we don't often question it. Thorn, however, has made a career out of running against the wind -- he typifies the American belief in personal invention and reinvention. His music isn't trendy -- that's because trends are superficial.

The title track of Thorn's first CD, Hammer and Nail, contains a verse about his fight with the Panamanian great. In 2010, "Pimps and Preachers" topped the Americana charts for three weeks and broke into the Billboard Top 100. His drew from the well of his family background. While his father, Wayne, is a Church of God reverend, his father's brother once slummed as a pimp, and Thorn was influenced by both of these pulls. Harvesting these "saint and sinner" contrasts, Thorn crafted a disc bubbled up from observations he made while considering the line between the two.

Boxing is not a team sport. You win alone; you lose alone. Thorn's brings that lone wolf mentality to his live performances every single night. Performing approximately 170 shows a year, Paul Thorn is certainly ambitious-driven. Sheer enthusiasm propels much of his journey.

"I try finding a few new fans a night. On a television show you can win a million fans in one night, but if you don't play hard or play well, you can't retain them. I'm all about shaking my fans' hands. And things are good. At a time when many businesses are falling by the wayside, my business is growing. Record companies are going extinct and record stores going extinct, so I use Facebook, Twitter and the Internet. There are a lot of people ahead of me, career-wise, but there are also a lot of guys behind me looking up."

At the end of the day, the beauty of music is more about human interaction and expression than it is about Google algorithm predictions. Basking in the warm glow of their own arrogance, some musicians forget that they play for others and that audiences want to be treated as people. Thorn believes that people respect authenticity, and, he says, he is proud to hold such a loyal following that will run through walls for him.

"When I'm done with a show, I don't just leave. I walk out there and start shaking hands, I can't just leave without shaking hands or signing things. It really goes back to my dad being a minister, you know, he told me that you got to love people. People can feel it when you are not interested."

One of Thorn's most enjoyable recent jams, "It's a Good Day to Whup Somebody's Ass," isn't about what you'd naturally think it would be about. "It's more of a novelty song about being tired of your boss, tired of life, tired of the cops, it's not about boxing. You'd be surprised how many times guys play it on morning radio shows."

Thorn is creative and open to innovation, he is careful to never corner himself into a rut; he's not living if he's not engaging in new experiences in the world.

Big ideas don't always occur in a formal setting, but great albums do. Thorn is currently recording a new work at a studio in Alabama.

"I'm just weeding things out. I've got no schedule as far as writing songs, the ideas come when they come. When ideas come, I jump on them."

Challenges in the recording studio seem trivial compared to three minutes of someone really trying to hurt you in the ring. Nonetheless, there is one person from his boxing days that he'd gladly reacquaint with.

"On one of the albums I did after my boxing career, I tried to get Roberto Duran to play the conga drums, but he was training to fight Hector Camacho, and he couldn't do it. Before I die, I would love to get Duran to play on one of my records. That's my goal."