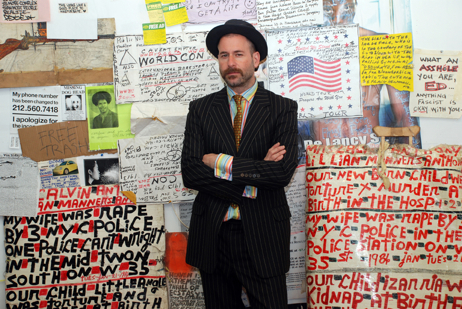

If writing and the avant-garde have a node point in 2011, it's poet and critic Kenneth Goldsmith. Over the last two decades he has popularized techniques of appropriation through his books Traffic (culled from traffic reports) and Day (one entire issue of the New York Times retyped). As a critic and editor in books such as the recently released Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age and the anthology Against Expression, he has supported an entire new generation of writers. (Full disclosure, my work appears in Against Expression.)

In May of this year Goldsmith was invited -- along with Common, Aimee Mann and Steve Martin -- to a night of poetry at the White House. Wanting to hear the story of the night without spin from Fox News or The Daily Show, I spoke with Goldsmith about his White House performance.

Brian Joseph Davis: When you read and spoke at the White House there was the conservative insanity over Common, and The Daily Show goofed on your suit. That's all expected to a certain degree. I was amazed though, and emboldened, that no one took umbrage with the fact that you were reading collated traffic reports to the President of the United States. When I'm presenting work, even to peers, I sometimes have a lapse of confidence about the value of what I'm doing. How did it feel going into that reading?

Kenneth Goldsmith: The GOP or Fox News could've had a much bigger controversy on their hands than they did with Common because unlike him, I actually break the law in my literary practices. In fact, I was able in the afternoon poetry workshop session with Michelle Obama, to advocate for literary uncreativity, unoriginality, plagiarism, identity theft, repurposing papers, patchwriting, sampling, plundering, stealing, file-sharing and so forth in front of the First Lady. Nobody blinked an eye. When discussing my entirely-appropriated book, Day, which is a transcription of a day's copy of the New York Times, I was interrupted by an engrossed First Lady who insisted on knowing what day I chose to transcribe. The lack of resistance to what I was saying was remarkable. In fact, The White House was the most frictionless place I've ever been. Nothing ever goes wrong there. Like walking on air or being on the moon, there's a complete lack of gravity. Due to the most insane security, it feels like the freest, most relaxed place on earth. It's like everyone is on a combination of Prozac and Ecstasy. And everything I said there seemed to be met with big smiles and nods of approval, even things that advocated breaking social contracts -- or even the law. Strange doesn't begin to describe it.

Similarly that evening, with the president sitting five feet away from me, I read appropriated texts. Again, nobody flinched. I put together a short set featuring an American icon, the Brooklyn Bridge, and presented three takes on it, first an excerpt from before the bridge was built from Whitman's "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry," then the bridge as metaphysical / spiritual modernist icon with an excerpt from Hart Crane's "To Brooklyn Bridge," finally finishing with an excerpt from my book Traffic, which is 24-hours worth of transcribed traffic reports from a local New York news station. The crowd, comprised of arts administrators, Democratic party donors, and various Senators and mayors, respectfully sat through the "real" poetry -- the Whitman and Crane -- but when the uncreative texts appeared, the audience was noticeably more attentive, seemingly stunned that the quotidian language and familiar metaphors from their world -- congestion, infrastructure, gridlock -- could be framed somehow as poetry. In fact, one could say that most of those in the room were talking heads, daily spouting words written by others. It's no wonder they felt akin to appropriative and uncreative writing. It was a strange meeting of the avant-garde with the everyday, resulting in a realist poetry -- or should I say hyperrealist poetry -- that was instantly understood by all in the room; let's call it radical populism.

BJD: I was talking recently with the poet Matt Timmons about the issues involved in producing this kind of work and Matt joked that after you presented conceptual writing to a head of state -- and let's be honest, one of the more important heads of state -- the implication was kind of like "Hey, we won." I think more than that, conceptual writing has been legitimated by the fact that the Internet has completely changed reading and writing, even for people who don't consciously think about reading or writing. Where do you see conceptual writing going, as a methodology or even a genre, after this?

KG: The Internet has completely changed reading and writing, but few people are willing to admit it or act as though this has happened. Just last week, the New York Times published this sentence: "Publishers are extremely sensitive to charges of plagiarism, considered among the gravest sins in the literary world, and in some cases are quick to respond." It's amazing how fucking out of it they are. I mean, really? Still? So there's a long way to go before we "win."

Ignoring such stupidity, in terms of conceptual writing's next move, I feel it will be in the direction of what's been known in the art world as institutional critique, a type of practice that takes as its subject matter the way that institutions frame and control discourses surrounding the art works that they exhibit rather than focusing on the content of the art works themselves. Conceptual writing began with legitimizing plagiarism as a literary practice but, having thoroughly exhausted that terrain -- need we appropriate the entire internet? -- has moved on to explore non- or anti-writing. Plagiarism is still concerned with traditional literary notions (the play between the original writer and the re-writer, and of course, is deeply engaged with a readership, either duped or complicit) and is still codependent upon the role of the author. We're far beyond death of the author; now we're talking about the death of literature. What remains are the structures and institutions surrounding literary production, which has now become, I think, the focus of postconceptual literature.

BJD: You teach uncreative writing at the University of Pennsylvania where you have students appropriate writing and plagiarize. I'm shocked that this shocks people but maybe that's my background in art rather than a traditional writerly education. What's the biggest change you see in your students by the end of your class?

KG: After a semester of my forcibly suppressing a student's "creativity" by making her plagiarize and transcribe, she will tell me how disappointed she was because, in fact, what we had accomplished was not uncreative at all; by not being "creative," she had produced the most creative body of work in her life. By taking an opposite approach to creativity -- the most trite, overused, and ill-defined concept in a writer's training -- she had emerged renewed and rejuvenated, on fire and in love again with writing.

The secret: the suppression of self-expression is impossible. Even when we do something as seemingly "uncreative" as retyping a few pages, we express ourselves in a variety of ways. The act of choosing and reframing tells us as much about ourselves as our story about our mother's cancer operation. It's just that we've never been taught to value such choices.

BJD: What, for you, is the perfect text?

KG: John Cage claimed that the best seat in the house is the one you happen to be sitting in. With that in mind, I can say that the most perfect text is the one I happen to be writing at the moment, which would make it this one.