It's starting to make me paranoid. My children never seem to hear my first three requests to pick up their shoes. The telephone sales reps never seem to grasp that I don't want a subscription to TV Guide. And the Chicken Delight delivery guy never--ever--remembers to bring the extra barbecue sauce.

And don't get me started on my wife and the bathroom light.

Is anybody listening?

Tuning out the world has, of course, been an irksome quirk of humanity ever since Eve famously dissed the don't-handle-the-produce command. Yet I've always assumed that poor listening skills are simply a behavioral flaw that most of us can keep in check, like nail-biting or binging on Mallomars.

But in her new book The First Word: The Search for the Origins of Language, author Christine Kenneally suggests that the I-can't-hear-you phenomenon might be more deep-seated than your typical marital disconnect or misunderstanding at the dry cleaners. It could be anthropological.

In recounting an experiment in which two apes, both versed in sign language, were thrown together and encouraged to chew the fat, Kenneally describes a surprising outcome: Rather than engage in a meaningful meeting of simian minds--a warm and fuzzy exchange about, say, the latest King Kong remake--the hairy pair immediately launched into an arm-waving row worthy of Ralph and Alice Kramden.

"What resulted was a sign-shouting match," Kenneally writes. "Neither ape was willing to listen."

If this monkey meltdown tells us something important about our capacity for listening--namely, that we're hard-wired to prefer the sound of our own voices to others'--it is also a blow to Darwin's theory. Because looking around the cultural landscape, it's obvious that, these days, we're tuning each other out more, not less.

Take last month's CNN/YouTube Democratic presidential debate. Admittedly, this experiment in political discourse didn't exactly reflect well on the journalistic sophistication of the average American (one participant actually spoke through an action figure of Aquaman, for God's sake), but the freshness of the YouTubers' questions gave the candidates an opportunity to come off-script for a change.

Too bad they didn't rise to the challenge. While the folks on screen candidly talked, laughed and even sang about their deeply personal concerns for the nation, the responses from behind the podia were largely canned excerpts from freeze-dried stump speeches--a juxtaposition that made the candidates' answers sound even flatter than usual.

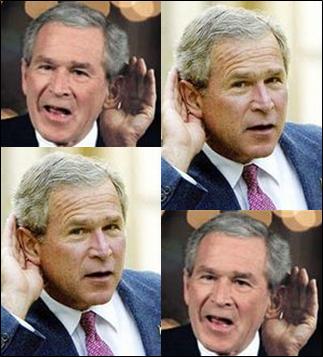

Not that the Democrats have a monopoly on deafness. After four-plus years of questionable listening, our president still clings to his calamitous war plan, even as a new UPI/Zogby Poll reveals that more than half the country no longer trusts his judgment as commander in chief. Add to this an administration that continues to snub congressional oversight, blow off the science community and plug its ears to the cries of frequent majorities (stem cells, anyone?), and it's safe to say that this White House has become positively Beethovian in its inability to hear the music.

Sadly, politicians are hardly the only ones on aural shutdown. It's only August, and already this year we've been witness to an unprecedented parade of the listening-challenged--from the sudden spate of spoiled starlets who told the law to talk to the hand, then landed in hot water (or jail) as a result; to the juiced-up cyclists who somehow didn't hear the repeated rules about doping, then pedaled themselves right out of the Tour de France; to CNN's money-man-turned-gas-bag Lou Dobbs, who wouldn't know how to listen if you gave the guy a third ear.

As we wade into a new election season, it's disheartening to imagine yet another campaign in which everyone's talking and no one gets heard. Then again, maybe one candidate will step forward and teach the rest how to listen. It's always possible, you know. After all, monkey see, monkey do.

This essay originally appeared in USA Today on August 16, 2007.