When the Beatles came on the scene in 1964, they scattered seeds of change -- musical and otherwise -- onto very fertile ground. By the following year, those seeds were blossoming and became part of the renaissance called "the sixties."

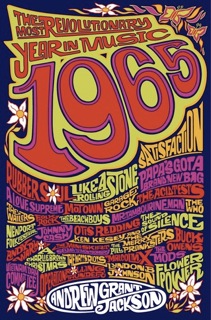

This mid-decade moment of enchantment is finally given the scrutiny it deserves in Andrew Grant Jackson's 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music. Many of us have been in heated discussion about which year of the sixties produced the "best" music -- that's a different and much more subjective question. But this book deftly supports the claim embedded in its title.

Written for music lovers who were there and for those who wish they were, the book is a well-researched cultural history that leaves no rolling stone unturned as it meanders through 1965, connecting dots to create a vivid picture of the cultural landscape as it looked a half-century ago. LBJ's Great Society programs, the assassination of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King's march to Selma, the arrival of combat troops in Vietnam, birth control, Merry Pranksters, draft card burning, Bill Cosby's television debut, granny glasses, the mini skirt, and the origins of flower power are all part of this vivid picture, but the emergent new sounds are always the centerpiece.

Of course marijuana and LSD are also important to the story -- very important -- and were major contributors to the unprecedented explosion of creativity that characterized the year. Most readers will come to this book knowing that many of these "new sounds" reflected a new, drug-inspired consciousness -- knowledge most music fans didn't have at the time. But fifty years out, Jackson's discussion of drug use among the year's key players reminds us anew.

Beatles, Dylan, Byrds, and Stones fans may wonder how these artists' works would have been different had they not been high -- one of the "what if" parlor games fans play -- but the passage of time sheds different light on the role of drugs not only on the music of '65, but on the music and cultural transformation of the entire decade. The overriding transformation, with the greatest thrust and energy, was the elevation of personal freedom and self-expression. That aha moment occurred for the greatest number of baby boomers on February 9 the previous year. This book shows how the events of '65 and the year's drug-fueled music brought lift velocity and go-go to the previous year's suggestion.

Jackson, also the author of Still the Greatest: The Essential Songs of the Beatles' Solo Careers and Where's Ringo, goes beyond pop, rock, and the new "folk rock," showing how R&B, jazz, and country were also undergoing dramatic change in '65, and he foreshadows glam, funk, disco, and hip hop. Stax and Motown are compared and contrasted within the context of Selma and Watts. At times, I felt compelled to check out some of Jackson's assertions and examples on YouTube, making for a lively reading experience. The few assertions I didn't buy were interesting observations nonetheless.

There are some familiar, oft-told stories: Dylan at Newport; Lennon, Harrison and their wives dining with the dentist, the Beatle-Elvis meeting, the Beatles hanging with the Byrds and Peter Fonda in LA, and other such moments. But when these stories are situated within this brief timespan their historical significance becomes clear.

One of the cultural transformations of the decade -- albeit at a still nascent stage in '65 -- was in gender roles. The birth control pill was becoming more widely available and had made its way onto college campuses. Jackson duly notes the profound sexism, no, misogyny, of many of the year's signature songs and shares an observation I make in Beatleness -- that the combination of explicit song lyrics, available birth control, and the resulting permissiveness without feminist consciousness meant increased exploitation of women, both in real life and in the media. Girl groups were on the wane, and with the exception of Cher and the Supremes, pop music in '65 was dominated by men -- though these men were sporting long hair, ruffled shirts, and Cuban heels.

The transition from beats to hippies is also an important part of the 1965 story. Jackson nicely gives Allen Ginsberg his due as an important transitional figure, one who may be unfamiliar to some readers -- astonishing as that may seem to generocentric boomers.

In a conversation about the book, Jackson said he "romanticizes" this historical moment and thinks it would have been "very exciting to live at the very beginning of the psychedelic era and sexual revolution, before the dark sides of those things had revealed themselves." His interest in the period was inspired by his parents:

I love the music because my dad played it when I was young and got me hooked on it. He'd been a professor in the mid-'60s, from a conservative background, and the '60s hit him head on. He switched careers to try to become a countercultural filmmaker, and got into transcendental meditation. He and my mom both got into Eastern philosophy and synthesized it with their Christian backgrounds. Since my parents were directly changed by the social upheavals of the era, history of the era fascinates me. It was a monumental year, but it's been under the radar in terms of music and pop culture books.

The most revolutionary year in music is under the radar no more.