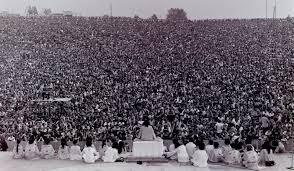

This week marks the 47th anniversary of the Woodstock Music and Art Festival, an event that epitomizes the spirit of the sixties. As I discuss in Beatleness: How the Beatles and Their Fans Remade The World, many music fans, age 12, 13, and 14 in 1969, bemoan the fact that they were "too young to go to Woodstock." Nevertheless, these young people felt a strong affinity with Woodstock Nation, watching the event on the news or looking at the photo spread in Life magazine.

Throughout the sixties, the Beatles exposed young baby boomers to new sounds, images, and ideas, and these youngsters were well aware of the counterculture. Those with older siblings were even more tuned in, and, in mixed-age groups, discussed it all in mind-expanding conversations in dens and on playgrounds across America. Many boomers born between 1955 and 1958 say they grew up faster because of the Beatles and the cultural tumult of the sixties, but were "too young to be real hippies."

Three years before Woodstock, these children listened closely to "Nowhere Man," a distinctly different kind of pop song. Lennon's clear, emphatic vocal challenged baby boomers of all ages to be actively engaged in the world and to have opinions about what they saw around them. Many fans said they heard the song as the Beatles telling them to "pay attention." Perhaps the conspicuous harmonic tone, about one-minute into the song, functioned as a clarion call to, what would emerge three years later, as Woodstock Nation.

A few months after "Nowhere Man," in the summer of '66, the Beatles presented young people with the equally emphatic "Rain." Through the metaphor of weather, this psychedelic song pointed out the foolishness of straight society. These songs helped define the contours of "the generation gap."

Then Revolver happened, presenting boomers with more psychedelic sounds and glimpses into altered consciousness. Some younger listeners recall being frightened by "Love You To," "Tomorrow Never Knows," "She Said She Said," and even "Eleanor Rigby." But they also remember intense conversation with older friends and siblings who helped them appreciate these songs.

A year later, during the Summer of Love, these same young fans (and Time magazine) saw the Beatles as the chief hippies. In those same mixed-age groups, they had "a splendid time" with Sgt. Pepper, engaging with the weirdness of the cover and the transporting music.

The half million baby boomers who showed up at Woodstock were those old enough to go, with or without parent's permission. But millions of tuned in tweens and young teens, now age 60, give or take a year or two in either direction, could not be there in body but were absolutely there in spirit.

Although the Beatles didn't play at Woodstock, Beatleness permeated the event in spirit and sound. Richie Havens performed three Beatle songs, and Joe Cocker and Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young each performed one.

Taking place less than two weeks after the Manson murders, which involved Beatles references written in victims' blood, Woodstock challenged the newly emerging perception of hippies, two years post-Summer of Love, as violent and dangerous.

The deadly stabbing at the Rolling Stones' Altamont festival four months later, while shocking and disturbing at the time, was, in retrospect, caused by a cascade of bad decisions on the part of the Stones' machine; violence was predictable. But a half million people at Woodstock, many on drugs and lacking basic necessities, remaining peaceful and cooperative, was extraordinary. When sixties historians discuss these festivals, the ordinariness of Altamont should not neutralize the extraordinariness of Woodstock.

Watching Woodstock on the news, John Lennon was moved by the unlikely peacefulness of a crowd that size, and felt that his messages of peace and love were having an impact. Indeed, the peacefulness of the huge crowd, happily cooperating under physically stressful circumstances, is why the event has maintained its luster and historical significance for those who reject the broader cultural cynicism towards the era of peace and love.

Joni Mitchell, who couldn't appear at Woodstock because of a previous commitment to appear on the Dick Cavett Show, was, like Lennon, moved by the event's historical significance and wrote "Woodstock," released In March '70 on Ladies of Canyon. That same month, Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young released their version on Deja Vu. Joni's version was more spiritual, more contemplative, and seemed to capture the singularity of the event, whereas the CSNY version has a more tribal, celebratory quality.

A month after these songs were released, the Beatles broke up. Then the first Earth Day took place. A few weeks later four students were shot and killed at Kent State while protesting the escalation of the Vietnam War. Fans' six-year journey with the Beatles was over, and so were the sixties.

Earlier on Huff/Post50: