The year 2012 marks the fortieth anniversary of my Puerto Rican mother and Irish-Italian father's unusual wedding. They met and married in an experimental community called Synanon, where I was born. Synanon was the founding model of the therapeutic community, but those who remember it are more likely to recall its tragic retreat into a cultish enclave in northern California. What few people know, however, is that Synanon committed itself to a program of racial integration throughout the 1960's and 70's. While it belongs to a bygone era of social experimentation, its deliberate effort to foster a racially inclusive society is worth remembering, especially at a moment in American history when the rhetoric of post-racialism masks ever-deepening racial inequality.

Chuck Dederich, a charismatic recovered alcoholic, started Synanon in southern California in 1958 to lift drug users out of addiction and despair. Not long after, Dederich began to envision its mission more broadly. Synanon, he proclaimed, would promote "a lifestyle that makes possible the kind of communication between people that must exist if we are to prevent this planet from turning into uninhabitable ghettos." In the 60's and early 70's it grew rapidly in size and prominence, with locations throughout the US, including Puerto Rico.

Synanon members, who came from every racial, religious and class background imaginable, lived and worked side by side. They also came together in "the game," a form of no-holds-barred group encounter therapy that was the focal point of Synanon's rehabilitation regime. At once intimate and confrontational, the game allowed people from all walks of life, and especially whites and blacks, to encounter each other in ways that would have been unimaginable elsewhere.

In 1963, at a time when interracial marriage was still outlawed in some American states, Dederich married Betty Coleman, a former heroin addict who had quit drugs in Synanon. Chuck told Betty that he believed "it would be good for Synanon to have, right at the top of the pyramid, an integrated marriage." Years after they wed, Betty recalled that Synanon's commitment to racial integration was the "common cause" they used "to bridge the gap, because there was no other way for us to get together."

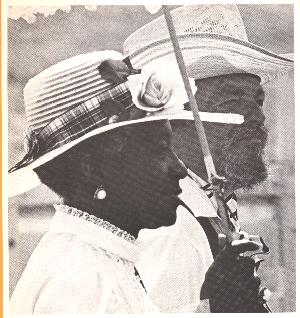

Dederich, a portly white man with a salt-and-pepper goatee, and Betty, a visionary black woman with graceful eyes, cast a striking image, but more than that they set an example for others to follow.

Indeed, a decade later my parents were one of 75 couples that tied the knot in a mass wedding on Synanon's sprawling ranch at Walker Creek. If you look closely at the sea of faces in their 1972 wedding photos there is one thing that stands out: many of the couples were interracial.

As a result, I grew up surrounded by white, black and multi-racial kids. Because everything from toys and clothes to showers and mealtimes were shared, a sense of equality structured my relationships with my peers. Even as a child I was aware that many things weren't ideal about Synanon and its ever-changing philosophies and dictums, but my early years in a multi-racial community, where mixed marriages and multi-racial identities were normalized, have shaped me for the better in ways I will probably never fully understand.

It was only after I left Synanon that I realized what an unusually integrated community it was. Even at the young age of eight, I quickly sensed how racially divided my new landscapes were. Not only were people of different races not living together in the same houses, they weren't living in the same neighborhoods.

While a new Pew Research Center study on interracial marriage in the U.S. shows that mixed marriages have reached an all-time high of 8.4 percent, and more Americans than ever before view intermarriage positively, these encouraging statistics should not lull us into believing that the project of racial integration in America has succeeded. The persistence of racial segregation and inequality in the country poses a significant barrier to the kind of cross-racial communication and understanding our society so desperately needs if we are to create supportive, encouraging environments not just for mixed-race families, but for all people.

Here is where I draw a valuable lesson from my early years in Synanon: creating a racially integrated society has to be a conscious choice. It requires acknowledging the racial divides that still mark our country in profound ways and a willingness to "bridge the gap," to borrow Betty's words, by forming interracial solidarities. Whether on the playground, in the classroom, in places of worship or in the home, we must seek out and seize opportunities to build a more racially inclusive society.

Not unlike other social experiments of its time, Synanon lost its way by the late 70's. While its unfortunate transformation into an isolated cult-like community cast a dark shadow over its clinical innovations, its downfall has altogether obscured its pioneering role in fostering racial integration. When I look back at my parents' wedding photos and pictures from my early childhood, I see a history that ought to be restored to its proper place in the annals of America's long and still unfinished road to racial equality and inclusivity.

Carina Ray, assistant professor of African history at Fordham University, is the author of the forthcoming book, Crossing the Color Line: Race, Sex, and the Contested Politics of Colonial Rule in Ghana.

A version of this article was first published in the Point Reyes Light on March 15, 2012.