The distinguished roster of over 100 dance artists who have danced with Alonzo King LINES Ballet since its founding in 1982 graces a page of the company's handsome 30th anniversary playbill; the names on that page alone bear testament to Alonzo King's profound contribution to the vibrancy and creativity of the San Francisco Bay Area dance scene. As generations of dancers come and go, we've come to expect a certain look from the company -- those taut, jaguar-sleek bodies with hyperextended limbs inscribing gorgeous lines in space -- and a certain sound often called "world music."

The company's anniversary program opened with retrospective excerpts from three works reaching back to 1994, followed by a new collaboration with composer-musician Edgar Meyer. While all four works are set to music from different time periods and genres, they all share the same aesthetic - thanks in large part to the design influence of Robert Rosenwasser, who costumes the women in the chic-est and flimsiest of lingerie, the men in tight trunks or silky pyjama bottoms, and the lighting of Axel Morgenthaler, who bathes the dancers in a golden light and drags plumes of San Francisco fog onstage.

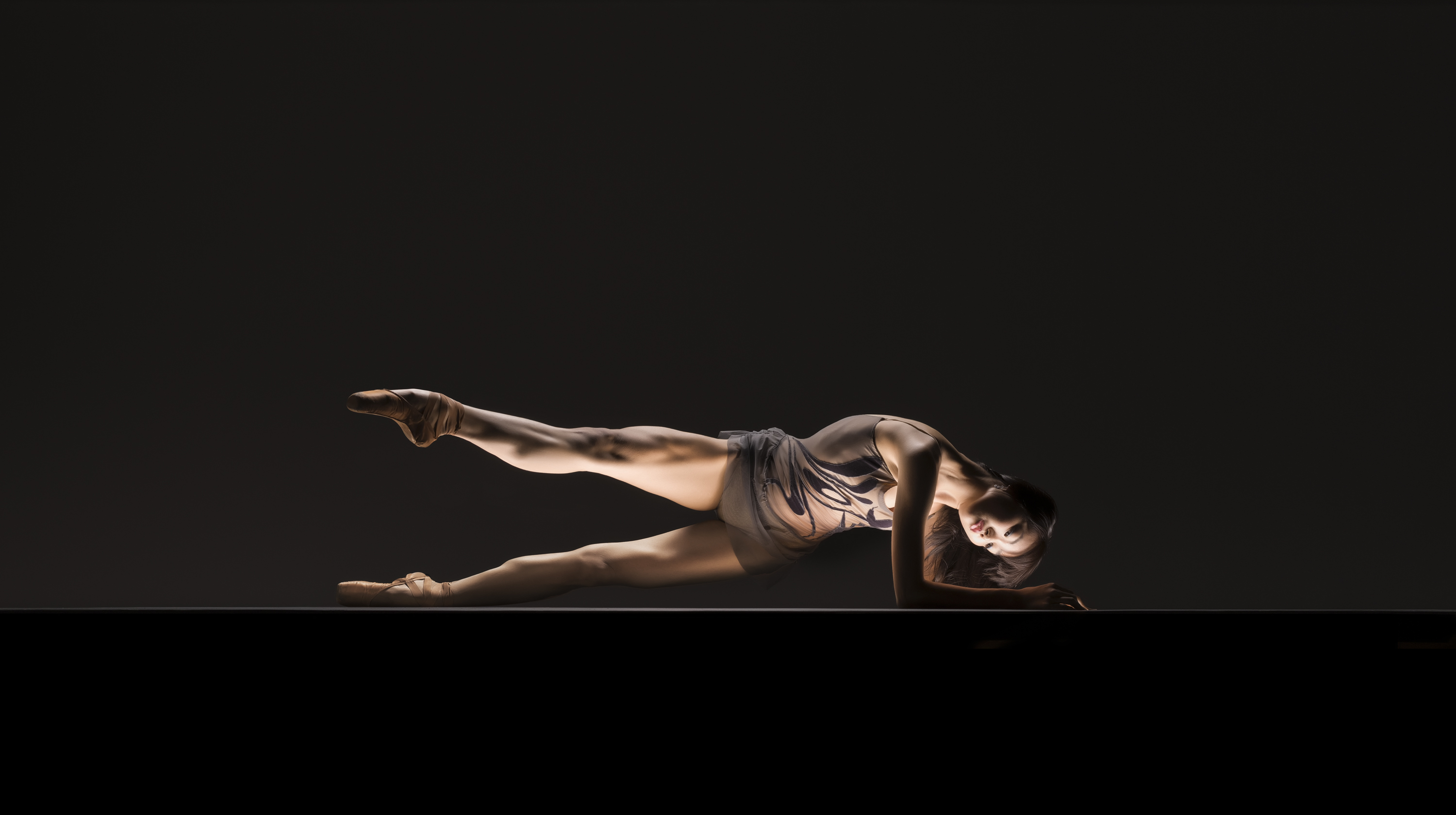

Keelan Whitmore (Photo: RJ Muna, courtesy Alonzo King LINES Ballet)

The four works also share the same sinuous movement vocabulary and the same structural randomness. The dancers rarely move in unison when onstage together, their pathways along the floor cut every which way, and their default gaze is inward or down to the floor. They rarely look out to the horizon, at the audience or at each other, not even when wrapped around each other in pas de deux. There are few patterns to the movement -- and without patterns and unison, there is little sense of the ritual from which much of classical dance, and even a great deal of modern dance, derive their power. These dancers don't seem to be dancing for us at all -- Alonzo King has liberated them from that responsibility, and has liberated us as well from certain musty conventions. We start to feel like voyeurs rather than folks dressed up for a night out at the ballet.

King's dancers appear to be swept up in the music, but they each seem to hear something a little different - which adds a layer of impenetrability to the dance. Once you stop looking for meaning, however, and just allow yourself to bask in the sheer heaven of those endlessly folding and unfolding limbs, those spiraling and unspiraling pirouettes, the elegant skids along the floor, undulating torsos, the cat-like landings from big airy jumps, you feel the kind of dreamy fascination that seized Jimmy Stewart in the early moments of Rear Window (before he suspected that one of the neighbors on whom he'd been spying might be a murderer.)

Unlike the Hitchcock film, however, suspense does not build in any of these pieces, and -- with one notable exception -- the thrill of all this physical beauty starts to give way to a sense of déjà vu. Like a restless child on a family vacation who has seen one too many billboards flash by, Ballet To The People kept wanting to ask "Are we there yet?"

David Harvey (foreground) and Edgar Meyer (background) perform in Meyer, Alonzo King LINES Ballet's collaboration with double bassist and composer Edgar Meyer (Photo: Angela Sterling, courtesy Alonzo King LINES Ballet)

Meyer, King's new collaboration with Edgar Meyer, treads the same choreographic ground as his older works. The high notes were primarily musical, particularly the soaring, wistful "First Impressions" for piano, cello and violin, and the penultimate movement, which put Meyer centre stage. The tail spike of his double bass driving into the floor and the gentle sway and swivel as Meyer put his instrument, and the dancers, through their paces mirrored the elegance of female technique on pointe. One wishes all three musicians could have been accommodated centre stage throughout the entire piece, to further cement the notion of a conversation between dancers and musicians.

In an eloquent interview with Mary Ellen Hunt, King insists that his work is not abstract, that his steps and shapes are "just like algebra... symbols for things that words are too clumsy for." There is always a story, he claims, and every step is a metaphor. But unearthing these stories and metaphors can be heavy going, even for the most avid ballet mathematician or archaeologist. Ballet To The People is reminded of a comment attributed to the great dancer Angel Corella:

Sometimes a choreographer wants you to have an idea, and sometimes you are the idea.

David Harvey and Meredith Webster perform in Meyer. A water set designed by Jim Doyle is in the background. (Photo: Angela Sterling, courtesy Alonzo King LINES Ballet)

There was much advance hype around the "watery scenic design" by Jim Doyle, who is credited with designing the lavish fountains in the eight-acre lake at the Bellagio in Vegas, among other masterpieces, so naturally Ballet To The People had imagined something on the order of Edward Clug's masterful Le Sacre Du Printemps in which torrents of water are unleashed onto the stage and onto the heads of the resilient but not waterproof dancers of the Slovene National Ballet. Doyle's creation turned out to be a tame two-dimensional screen comprising thin streams of water -- in effect not much different from a scrim made of strings of shiny metal beads, apart from the series of agreeably syncopated drips and splashes that provided a complementary bass line to the intriguing score played live by Meyer's trio. For one brief, light-hearted moment, a dancer stepped up to the edge of the trough that held the water and stuck his hands and feet and then his head under the dripping stream -- more like a kid playing under an open fire hydrant than a love-struck Gene Kelly risking pneumonia. Otherwise there was no interaction between man and force of nature, just an attractive prototype for the next casino water feature. Morgenthaler did his best to stir things up with the lighting, at one point turning the stage floor a bright green, perhaps to suggest the advent of a verdant Spring after all that rain (or maybe Ballet To The People just has too much Rite of Spring on the brain in this centennial year of the Ballets Russes masterpiece, though she could swear the final Meyer composition had Stravinskian overtones and, uncharacteristically for Alonzo King, outbreaks of heavy Nijinskian stomping.)

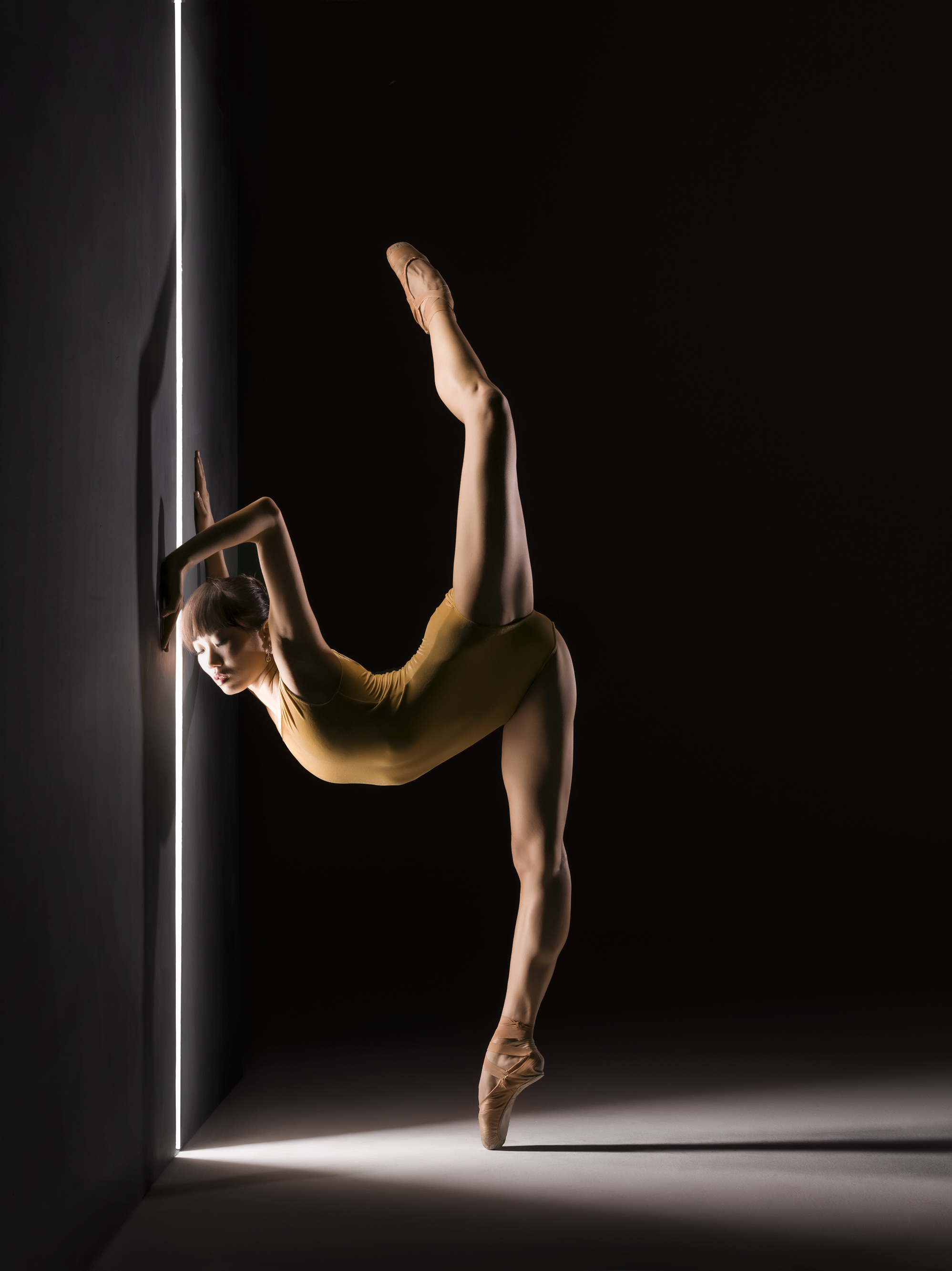

Paul Knobloch and Kara Wilkes (Photo: RJ Muna, courtesy Alonzo King LINES Ballet)

The stand-out piece of the evening was a heartbreaking fragment from Writing Ground, which on Saturday evening featured Kara Wilkes in the role of a woman damaged by some unrevealed trauma. As she staggers valiantly across the floor, David Harvey, Paul Knobloch, Zachary Tang and Keelan Whitmore step in to support her, at other times to restrain her, manipulate her, even abuse her. Recent tales in the news of horrifying cruelty to women inescapably come to mind. Wilkes abandons the enigmatic bearing typical of King's dancers, a cascade of emotion, from fear to defiance, exhilaration and exhaustion, registering in her face and body. She tears up the stage in a searing performance that illustrates the power of Alonzo King's story-telling at its height.