George Haimsohn

A devoted scholar of femininity, Candy's life was a tribute to that sorceress womanhood that had cast a spell on her--the very same one she would later wield against others. Candy Darling had a way of eclipsing everything else around her, on stage, screen, and in the theater of life. Maybe it was that hair--golden blonde and billowy, and, like the woman beneath it, almost incandescent; or maybe it was her eyes, some inner spark shone outward, at once brassy and delicate, feral and fragile.

Able to embody a stunning spectrum of selves, Candy was an encyclopedia of female archetypes. As a result, her every word and gesture were a tribute to the ladies in whose image she had built herself. There was in Candy the femme fatale, the southern belle, the damsel in distress, the man-in-a-dress, the soubrette, the coquette, the vamp, the lady, and the tramp.

Like many beautiful women, she projected an enigmatic quality that could be filled in by the fantasies of her audience or lover; and who, after seeing Candy footage, doesn't feel a bit like they've slept with her--and that it was very, very good? Unlike many beautiful women, however, she wasn't born one.

Andy Warhol's transsexual superstar entered the world as James L. Slattery in 1944 (although the date has been contested) and left it (as a result of cancer) as Candy Darling in 1974. James Rasin's moving documentary, Beautiful Darling (2010), explores the process by which she became the ravishing dame that she did. By chronicling Jeremiah Newton (the film's producer and one of Candy's closest friends) on his quest to bury her ashes with those of his mother; individual memories (provided by Fran Lebowitz, John Waters, Paul Morrissey, Taylor Mead, and Penny Arcade, among others); and childhood photos, doodles, and diary excerpts, Candy lives again. Fortunately, Newton, Rasin, and Arcade were kind enough to reflect on that remarkable life with me in an interview.

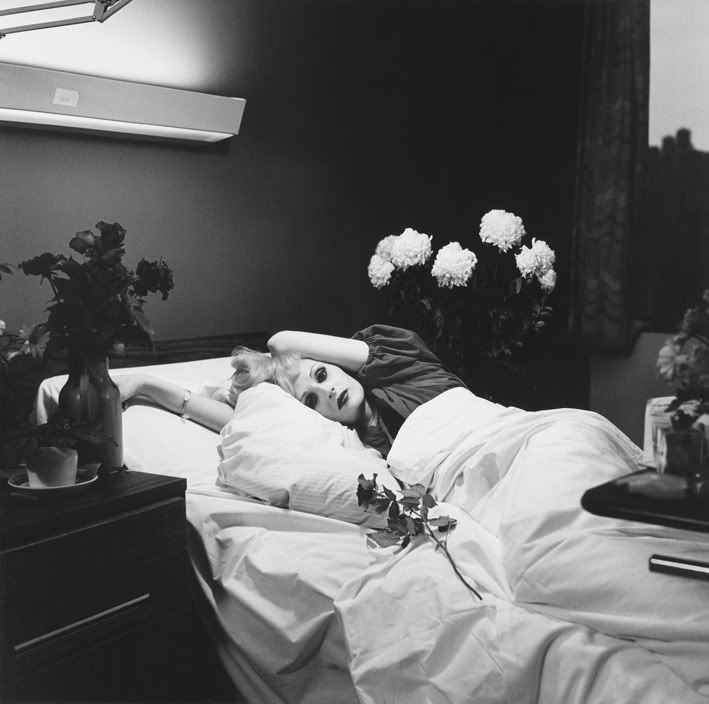

Although Candy's acting career included Alan J. Pakula's Klute (1971), a couple of Warhol films--including Flesh (1968) and Women in Revolt (1971)--and even a Tennessee Williams play, Small Craft Warnings, her life was her greatest showpiece. Rasin's film considers her biography as a whole, but focuses most keenly on her obsession with attaining the elusive properties of fame, beauty, and femininity. From her early years doodling film stars in school notebooks to her final days of posing for Peter Hujar's famous photograph, "Candy Darling on Her Deathbed," she built her own identity out of these desires.

Peter Hujar

Candy reminds us of the postmodern notion of self-creation--the way we don social signifiers with the same ease as clothing, constructing our selves bit by bit from cultural cues and images. Rather than the solid frameworks we cast them as, our selves are more like sweaters we put on and take off. When it comes to social identity, we're all a wee bit in drag.

In keeping with this gender illusionism, Candy was both a work of art and the artist who created it. When asked who Candy was when she wasn't in the public eye, Newton could only talk about what she looked like without make-up. On the topic of what it was like to see her transform from unknown to Factory star, he said that she was already transformed when he met her (as a teenager). Nestled in her semi-satirical interpretation of womanhood was quite the education in Hollywood starlets, since, as Newton notes, "she manufactured herself through movies." Clearly, Candy never put her act down.

Yet, in addition to her fabulousness, the film also examines the heartbreak at the core of Candy's circumstance. Although she strove to construct herself just as she wanted to be, there were certain issues that she couldn't build over no matter how glamorous she was. The proverbial cavern that stretched between her fantasy and her reality caused her deep pain, especially since her real world was punctuated by little tolerance and lots of conformity. Arcade frames this tension between what Candy dreamed of and what existed for her in the following way: "Candy, who transcended so much through her own spirit and creativity and belief in herself, could not pierce the membrane of the real, philistine world together."

Beautiful Darling captures the provincial mentality Arcade refers to most powerfully in an archival audio interview with an anonymous childhood friend of Candy's. This "friend" tells Newton that she severed ties with Candy after seeing her dressed as a woman. "A lot of people thought this type of person should be put away," she says, as if this excuses her actions. Indeed, in those times a man could be arrested for appearing in drag. As the film-revealed Candy expresses, the men who loved her would have killed her if they knew what she really was. People can handle ambiguity in art, but not in human beings. As a result, Candy gave them their answer: woman, not man; woman, not cross-dressing man; and not just any woman--Marilyn freaking Monroe with a secret penis.

(Candy Darling and Andy Warhol) Anton Perich

In her diary, Candy writes, "I've been up all night alone, wondering about my identity. Trying to look for an explanation for living this strange, stylized sexuality. Realization cuts feeling off. I try to explain my identity as being a male who has assumed the attitudes and somewhat the emotions of a female. I don't know what role to play." In the end, Candy was neither man nor woman, but something else entirely--a creature of fascination and desire from a faraway place. What was so revolutionary about her wasn't merely her status as a transexual; it was a certain polymorphous quality, an ability to straddle multiple identities at once.

This ability made her a bizarre symbol of the American Dream -- that carrot of promised, yet rarely delivered, success and belonging held out to outsiders. Hovering between old Hollywood and the avant-garde Factory scene, femininity and masculinity, narcissism and insecurity, Candy inhabited a sort of interstitial social space. Paradoxically, in becoming a complete creation, she got closer to what she really was. She aspired to an oxymoronic ideal of true artifice, and she ultimately became her own desire. Even after Beautiful Darling, Candy remains a clever trick played on everyone including herself, a ravishing riddle for the ages.

Remarkably, these contradictions didn't cancel each other out, but were the building blocks of the alternate dimension that Candy seemed to inhabit. It was her peculiar positioning in this space between traditional definitions that gave her an otherworldly quality. More remarkable still, while they watched her, viewers could leave their dreary, conventional existences behind and be whisked away to that mesmerizing world. In spite of her sultry ways, the sexiest thing she offered these people was subversion -- a chance to live, however briefly, as the person they knew in their hearts they were, but were afraid to show the world. Above all, Candy provided people with the vicarious thrill of being something other.