Saws screech as people bend over work benches in the bright, cavernous space of ADX Portland, making tap handles, furniture, razor handles, chandeliers, signs.

It seems unremarkable at first glance - people making stuff - but it's a collective makerspace heralding a profound shift in manufacturing that observers say will ultimately change what, where and how we buy our possessions in the United States.

The vision: we will buy fewer things, but they will last longer. They will cost more but that money will grow local economies. Revitalizing manufacturing will help rebuild the middle class. Over time, this will break the relentless cycle gripping most Americans: purchasing cheaply made products from overseas that break and are thrown in a landfill because it's less expensive to buy another one than fix what broke.

As ADX founder Kelley Roy asks: how many crappy vacuum cleaners have you bought in your life?

ADX is a central part of Portland's maker movement, a place Roy founded to knit together an emergent trend of people diligently making things by hand. It's a new kind of artisanal manufacturing in cities all over the U.S. that's replacing traditional notions of industrial manufacturing.

"It's a rebellion against the homogenization of products," said Adam Friedman, executive director of the Pratt Center for Community Development in New York and a founder of the Urban Manufacturing Alliance, of which ADX is one of 300 members from 70 cities. "There's a sense people want something that's better made and that will last longer, for both aesthetic and environmental reasons."

A place like ADX democratizes the entry point into manufacturing. You don't have to invest in expensive equipment to take a shot at making for a living. There are tools here, 3D printers, laser engravers, industrial sewing machines, saws, planers and joiners as well as other makers to consult. You can take a chance without risking too much. Since it opened in 2011, more than 75,000 people from Germany to Japan have toured this entrepreneurial creative hub. The White House has taken notice: it invited Roy to a national makers roundtable in May to discuss ways of helping makers become start-ups.

"What's different now is that the ease of entry has changed radically," said Charles Heying, an associate professor of Urban Studies & Planning at Portland State University who wrote the book, Brew to Bikes: Portland's Artisan Economy. "You can get into manufacturing more easily than you've been able to in the past: the tools are less expensive and those tools can do amazing things."

And everything else a budding entrepreneur might need can now be contracted out: payroll, accounting, taxing and marketing.

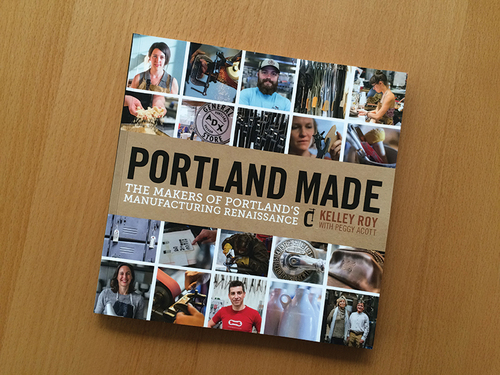

But what's happening in Portland goes beyond ADX to small manufacturers scattered throughout the city who are making everything from lamps to ceramic growlers, to window inserts to stained glass. Roy, gifted with seeing the big picture, has compiled all she sees happening in her new book, Portland Made: The Makers of Portland's Manufacturing Renaissance. It's a microcosm of a shift taking place across the country.

"Rampant consumerism happened over my life," said Roy, 43. "That's been the focus of our culture and economy and it feels empty at the end of the day. You're surrounded by stuff, by a bunch of garbage. People used to buy things that were well built, and people would pass them on to their children."

When Mudshark Studios first came out with handmade $65 beer growlers, co-owner Chris Lyon wondered who would pay that when a glass one costs $7. Lots, as it turns out. The Portland ceramic studio, where a half dozen employees' dogs freely wander, distinguishes itself by executing the ideas of independent designers so they can be entrepreneurial without investing in a shop. The company, which started in a basement eight years ago, now has 30 employees.

A lot of small manufacturers have told Heying the production processes and associated labor are less of a challenge than other aspects of the business: marketing, social media, staying on top of design trends and customer service. He sees artisans modeling how the emerging economy will look from the quality of the products to organizational structures.

"Urban economies in the early part of the 21st century will look a lot more like an artisan economy than they will the industrial economy of the century past. And while most artisan enterprises will remain part of the essential understory, some few will find the light and become the vigorous stands of a renewed economy. So nourish the understory, the old trees are falling."

In just five years, Indow - another Portland maker Roy highlights - has grown to 30 employees and sells its handmade window inserts across the nation as well as in Canada. Sam Pardue, long worried about climate change, invented the silicone edged insert to block drafts and make homes more energy efficient without damaging historic wood windows. It's the kind of manufacturing that could never go overseas because each insert is custom made using precise laser measurements. The shipping costs and longer lead times would outweigh any labor savings.

It's hard to document the artisanal manufacturing renaissance with government numbers. Manufacturing jobs were at 12.3 million in November, up six percent over the past five years but down 15 percent from 10 years ago, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. But that may not include many businesses profiled in Roy's book. In a survey of the Portland Made collective - a self-identified group of artisan makers and manufacturers - 86 percent didn't show up in a standard database commonly used to identify similar businesses, Heying said.

He speculates periods of innovation and enterprise occur in roughly 30 year cycles. Portland in the late 1970s saw a number of artisan manufacturers build businesses like Bullseye Glass, which supplies stained glass around the world using a 17th century process that involves shoveling molten glass from furnaces. Portland and other U.S. cities are experiencing another wave now.

Photo credit: Aaron Lee

But in order for this urban manufacturing renaissance to continue, national financing programs have to make it easier for manufacturers to get low interest loans, Friedman said. Industrial development bonds favor those who own their space - and most urban manufacturers rent.

Also, health care costs have to come down.

"If you want an entrepreneurial society, you can't inhibit people from starting a business because they don't have health care," he said.

Artisanal manufacturers don't shy from talking about trying to pay living wages of at least $15 an hour, something openly discussed at Roy's standing-room-only book launch at Powell's. They value sourcing local sustainably harvested raw materials, providing health care and keeping prices affordable to all while trying to make a reasonable profit. Roy sees the maker movement as a political platform for needed change.

"Pay people more so they can afford to buy well-made local products (and food that is good for them), which is the way toward rebuilding the middle class," she said.

Roy sees the manufacturing renaissance encouraging consumers to think about the way they purchase products in much the same way the push for locally grown food has started to change how they eat.

"Don't underestimate the power of this movement," she said. "America is making again and this "industrial revolution" is being fueled by people with deeply held values."

Carrie Sturrock is a writer and company storyteller for Indow in Portland, Oregon.