Abstract Expressionist New York at MoMA

October 3, 2010-April 25, 2011

Mark Rothko (American, born Latvia. 1903-1970) No. 5/No. 22. 1950 Oil on canvas

9' 9" x 8' 11 1/8" (297 x 272 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist.

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Museum of Modern Art, for quite a while now, has been experimenting with curation as the one arrow in its quiver that can restore vitality and even relevance to the old fashioned museum business model. In these days of social media and intimate digital connection, museums can seem largely irrelevant: their content, unchanging: their atmosphere, didactic: their canonical approach to display and cataloging, static.

To counteract this, in the past few years, and to leverage the new technology that has become a sort bugaboo to museums seeking to bring in young viewers, MoMA has embarked on a series of experiments, most of them quite successful.

They have introduced new curatorial talent in order to support the challenge represented by performance and installation art, as well as a growing body of visual art.

They have displayed a penchant for heroic collection practices, such as procuring the @ symbol, as well as Tino Sehgal's Kiss.

They have launched a new app for planning visits and exploring the museum and for freely sharing images.

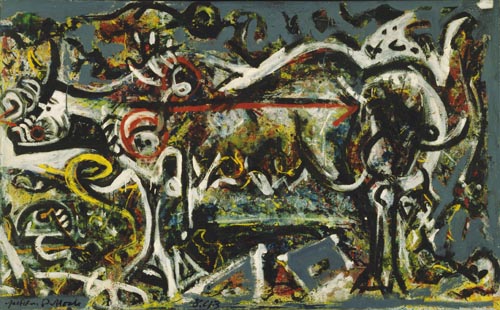

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956) The She-Wolf. 1943 Oil, gouache, and plaster on canvas, 41 7/8 x 67" (106.4 x 170.2 cm) Purchase © 2010 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

And, now, they have introduced "The Big Idea" a sprawling retrospective of Abstract Expressionist art, that focuses on the human element of sharing instead of the usual historical time line. Art as mutual curation, if you will, where the WWII-influenced community of artists and dealers in New York City, picked through and singled out the most relevant ideas, techniques, and values of their time.

Australia. 1951 Painted steel, 6' 7 1/2" x 8' 11 7/8" x 16 1/8" (202 x 274 x 41 cm), on cinder block base, 17 1/2 x 16 3/4 x 15 1/4" (44.5 x 42.5 x 38.7 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of William Rubin © Estate of David Smith/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

It is, of course, marketing as much as it is retrospective: The MoMA has emphasized that the show was drawn exclusively from it's own vast collection, art which it was very intimately associated with promoting and preserving -- and it has re-contextualized that collection, into a show that is all about, well, re-contextualizing. It's a great way to advertise a very fine collection and to add to their reputation as a cutting edge institution that is beginning to defy the traditional museum role as a mere keeper of keys. It's also deftly META.

Outside of the marketing slant that underlies, and makes ironic the title, "The Big Picture" is all about networking, sharing ideas and visual information. Forget zeitgeist, the elements and sentiments shared by the abstract expressionists are not, in this exhibit, ghostly, they are tangible trading cards: symbols, color, spaces and voids

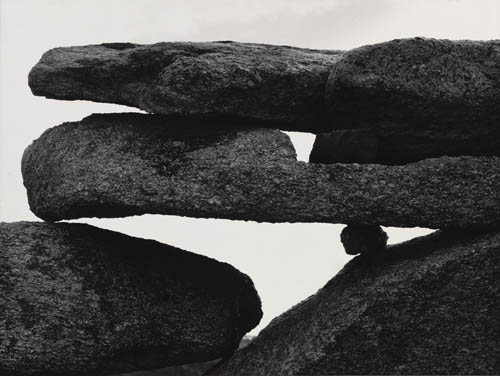

Aaron Siskind (American, 1903-1991) Martha's Vineyard. 1954-59 Gelatin silver print, 12 7/16 x 16 1/2" (31.6 x 41.9 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase © 2010 Estate of Aaron Siskind

Concentrating on painting, photography, and sculpture, the show's main body of works is dotted with surprises: early experiments with symbols and forms as well as with media are shared and passed from artist to artist. Viral letter-forms and hieroglyphic-like symbols bounce around the galleries from a Lee Krasner to an Adolf Gottleib, to a David Smith sculpture. Biomorphs float through Arshile Gorkys into Robert Motherwells, tenacious human forms refuse to exit the stage staring one-eyed out of an early Jackson Pollocks and poking heads up into later Philip Gustons, compositions are echoed throughout with simple split canvases, swirling centers, and lots of strict verticals and horizontals.

Blast, I 1957 Oil on canvas, 7' 6" x 45 1/8" (228.7 x 114.4 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Philip Johnson Fund © Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

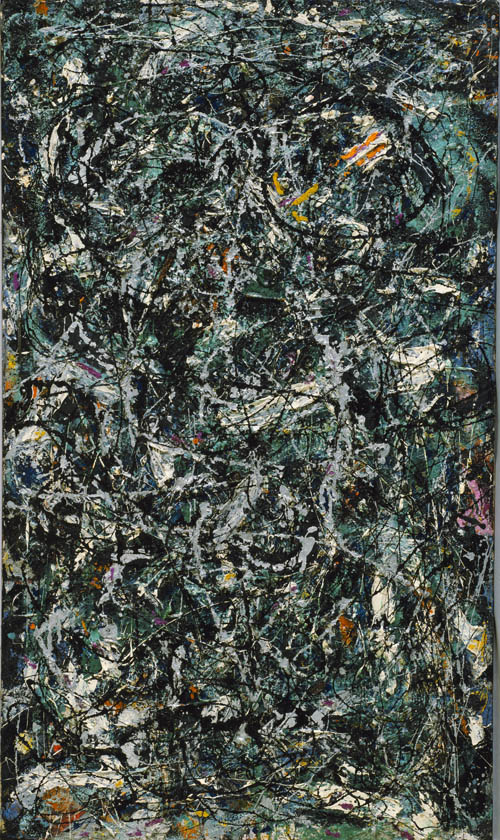

The exhibit is sprawling, taking up the entire fourth floor and galleries in the second and third floors as well. One finds rooms that show an historical arch and rooms that trace individual careers: the re-shuffle reveals connections in a way that solo shows or strictly historical timelines cannot. Early Pollocks with almost dorky figures peering through or with flat, broad color surfaces certainly give one pause: while the density and texture of the earliest drip painting in the show, Full Fathom Five (1947) shows that drip was only one thing on Pollock's mind as he echoed the painterly textures and deep color palettes of his peers, like Richard Pousette-Dart whose deep sand-textured oils resemble split marangues on top of his canvas.

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956) Full Fathom Five. 1947 Oil on canvas with nails, tacks, buttons, key, coins, cigarettes, matches, etc., 50 7/8 x 30 1/8" (129.2 x 76.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Peggy Guggenheim © 2010 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Supplementing the big picture, separate exhibits, arms of the show, concentrate on drawing and literature. Rock Paper Scissors, concentrates on sculptures and works on paper, pairing and echoing them to show shared forms and ideas about space. And Ideas, Not Theories, attempts to capture the culture, both intellectual and social, that the Abstract Expressionists lived in. These galleries are not to be missed and, indeed hold some of the very finest work in the exhibit, with Isamu Naguchi sculptures and drawings, two very nice Louise Nevelsons.

All in all the show is mighty comprehensive and really does show off the museum's history-making role in putting together such a complete and revealing collection. Much kudos to the curatorial teams who managed to make the old look new again.

Robert Motherwell, (American, 1915-1991) Elegy to the Spanish Republic, 54. 1957-61 Oil on canvas. 70" x 7' 6 1/4" (178 x 229 cm)

Museum of Modern Art, New York. Given anonymously © Dedalus Foundation, Inc./Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

But in all honesty, I was disappointed that -- although the MoMA's shifted emphasis, from individuals or historic time lines to a network of shared ideas and context, was interesting and even a bit exciting -- this show did not shift the main narrative which was always about men, always about WWII and a new idealism, always about a shift from narrative to form and process, and finally, always -- always and forever, about a large Pollock room, where the press gathers for comments and the speakers stand at a podium parked in front of One: Number 31 like an alter piece.

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956)

One: Number 31, 1950. 1950 Oil and enamel paint on canvas 8' 10" x 17' 5 5/8" (269.5 x 530.8 cm) Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection Fund (by exchange) © 2010 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I guess I was ready for a revolution but got another textbook instead. Silly me. No one can resist the radicalism of the drip. It is the culmination of abstraction married to process.