A serial about two artists with incurable neurological disease sharing fear, frustration and friendship as they push to complete the most rewarding creative work of their careers.

In Hadley's studio, one of the two panels for the Montana Women's Mural Project begins its life

Read Episode Twenty-Seven: Alpha-Synuclein, the Mental Marauder. Or, start at the beginning: An Illness's Introduction. Find all episodes here.

On December 5, 2013, five months after she was diagnosed with multiple system atrophy, Hadley received the thrilling news that she had been selected to be the artist for the Montana State Capitol Women's Mural. She signed a memorandum of understanding a few days later and eagerly awaited the contract that, once signed, would provide a deposit for her work. The timing for this was critical, as Hadley and John were burdened with several large medical bills.

There was more good news: The Stephen King Haven Foundation, which Hadley had applied to in November, had granted her $7000. And, she finally managed to secure affordable healthcare for her family. For days, she'd been trying to sign up on healthcare.gov but the website had been jammed; awake one morning at three-thirty, she finally got through. The new insurance plan was significantly more affordable -- they'd been paying $1100 per month with their old insurance and their new fee would be $780. With their old plan, her family's individual deductibles added up to $26,000 and didn't include prescriptions; the new plan offered a family deductible of $2500 and prescriptions would be free. These financial gains were an enormous relief for Hadley and John.

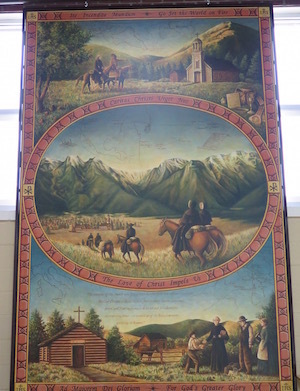

In addition to her talent and experience with painting history-themed murals, two other factors had made Hadley's proposal especially appealing to the selection committee. The request for proposals had asked for a single mural on the east wall under the barrel vault of the Capitol's third floor, but Hadley felt a second mural on the west wall would create a more balanced composition for the space. In effect, she was offering them two murals for the price of one. One panel would depict the lives of Montanan women, both settlers and Native Americans, during the mid to late 1880's, pre-railroad; the second would illustrate women in roles of leadership, entrepreneurship, social activism, and service following the arrival of the railroad and the 20th century. Another strong selling point was that she stressed her interest in approaching the project collaboratively in all phases. Part of her proposal read:

The best and most important part of any project is the collaborative work that goes into design and painting elements... if selected, the Artist looks forward to collaborating...Details about clothing, choice of women illustrated in the mural, subject matter, colors, final presentation, and all aspects of design are elements that become even richer when collaborated on and thought out as a team.

When Hadley received the contract for the Montana Women's Mural one week before Christmas, she was excited and terrified. From small things said and unsaid, she gleaned that she'd nearly lost the commission to one of the other finalists who pulled out of the process because of scheduling conflicts. In light of this, the committee's repeated praise for Hadley's spirit of collaboration temporarily shook her confidence, making her wonder if they doubted her artistic abilities. At night, she lay awake worrying. There was, of course, the expected nervousness any artist would have about whether they had the skills to meet expectations for this major public project. But also, what if she became too sick to follow through on the mural -- would it be possible to get help with it? Once the project was underway, would she be able to be honest about her health situation, or would she have to put extra energy into hiding it?

The schedule for the mural project would be tight. Hadley would need to complete a design by mid-March and deliver the two finished panels to Helena by mid-October, 2014. In November, they would be unveiled in honor of the 100-year celebration of the women's suffrage movement in Montana.

With the Women's Mural Project looming, the pressure was on for Hadley to finish the murals for the Missoula Catholic Schools.

Also in progress was work for the University of Montana Department of Forestry and Conservation. In the 1930's and 1950's, the department had commissioned an artist to paint scenes of logging and now, they wished to complement these with illustrations of post-1950's conservation work: the restoration of rivers and streams, controlled burns and protection of wilderness areas. In the mornings, Hadley scaled a stepladder at the Loyola Sacred Heart School to work on finishing the twelve-foot-tall murals there; in the afternoons, she'd work on laying out the designs on the three, five-foot-tall Forestry murals for the University. Her pattern was to work intensely when she had the energy and then crash for a day or two. "I need to keep going while I can because I feel like I'm at the bottom of a huge mountain and if I stop, I'll never be able to get going again," she told me. Standing for long periods of time was exhausting and often made her dizzy. Her hands cramped up and big movements with her paintbrush were difficult enough that she worried the paint would dry faster than she could keep up with it. And her balance had deteriorated to the point that she had to be ever vigilant to avoid falling.

Late at night getting ready for bed, she'd look in the mirror and wonder about the stranger looking back at her. Her face was losing its animation and softness, no longer expressing the spark she felt inside. She told me there was some relief in knowing that at least the finished murals wouldn't reveal her struggle to create them, "working from the cage" around her body.

Hadley had another critical task to attend to before the start of the Montana Women's Mural--creating a large enough work area in their home to execute the two five-foot-by ten-foot panels. Her painting studio was in a large room upstairs in her house, but she would need to expand into an office area that was crammed with files and paperwork generated by thirteen years of her artist's practice. She dug in, dismayed to discover that mice had taken up residence in the piles of old contracts, drawings and research. Most of the files had to be discarded and the rest sanitized. It was a physically exhausting ordeal, and emotionally trying to go through the business of her past. She couldn't help wondering: will I be around in another thirteen years?

Several weeks after signing the contract for the Montana Women's Mural, Hadley drove to Helena to meet with the mural committee members -- former state Senator Lynda Moss, who has a background in art and history and has worked extensively in community development; Mary Murphy, a history professor at Montana State University who has a special interest in women's history, gender in the American West and American women; Kim Hurtle, a member of the Montana Arts Council; and Julie Cajune, Executive Director of the Center for American Indian Policy and Applied Research at Salish Kootenai College and Director of the HeartLines Project. Julie is also a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. The collaboration of these women professionals exemplified the murals' theme of "women as community builders."

Hadley felt honored to be working side-by-side with such accomplished women. As they discussed the issues they had with her original design and brainstormed solutions, she was invigorated by the conversation. But at times, she realized they were veering away from the subject of "women as community builders" and after the meeting, she kicked herself for not having had the presence of mind to pull the conversation back on course. As an excellent listener, conceptualizer and with a great memory for details, she'd always felt on top of things at meetings; if the discussion digressed, she would be the one to rein it in so that everyone would leave with a strong sense of direction.

This time, Hadley came away from the meeting muddled and realized she was very likely experiencing mild cognitve impairment, a symptom of her disease. During a follow-up conference call, she didn't contribute much, but listened hard to her collaborators' ideas and questions while they tried to nail down the mural's content. Her mind churned--how would she convey all the ideas discussed on the two canvases? She'd determined that each painting would be grouped into several sections: a large center image within the shape of an oval surrounded by four small corner images. Scenes from Montana women's history would fill the two ovals; one would depict Native American women trading goods with European American women, perhaps medicine and food for cloth. To contrast with this rural image, the women discussed creating an urban scene for the other mural's oval. Hadley wanted to make the scene more poignant than a simple depiction of life "in town" and the committee exchanged ideas about images that would reinforce the community-builders theme. They settled on an illustration of the women's suffrage movement. The four corner pieces bracketing the two ovals would add supporting images: women digging bitterroots, women sewing or beading, teaching, nursing, canning, women with children, as aviators, cowgirls. Hadley felt more settled after the conference call, but still not satisfied that the ideas for the mural were gelling.

In the meantime, Montana, like other areas of the country that winter of 2014, was experiencing one of several "polar vortexes" and daily, temperatures plunged to the negative digits, worsening her stiffness. Missoula was plagued by storms that would break a 1939 snowfall record. An avalanche slid down Missoula's Mount Jumbo, burying the house of Hadley's friends, a couple in their sixties; the man was pulled from the snow and survived, but tragically, his wife died from her injuries.

The week before her big mural meeting, Hadley had planned to do research at the library but when Sarah came down with a virus, she didn't leave the house for four days. If she'd felt confident in her vision for the project, such a delay wouldn't have thrown her, but the disruption came at a sensitive point in the process. Her spirits sank with her energy. She told me her mind felt like a huge messy pile she had to sift through every time she needed to find something, mirroring the actual experience of sorting through her collection of images and her own paintings to pull visual elements for the murals. Sometimes, she would forget what she was searching for; other times she'd lose track of what she'd found and what she was going to do with it. An added frustration was that it was taking her longer to complete tasks that in the past would've been simple for her -- a drawing that might have taken several hours to complete just a couple of years ago was taking her several days.

It was a Herculean task for Hadley to fend off anxiety about what was happening to her mind and body so that she could drive the mural project forward.

She rallied. The next week, on February 20, she would have a meeting with the committee in Helena and she scolded herself: "Get your act together." At least the four days at home with Sarah had allowed her necessary rest, and her body felt stronger. She pulled out her computer and organized the documents and notes from her design discussions, made a list of all the ideas that had come forward, and spent the next three days researching images that would illustrate those ideas. One of her most exciting finds was a photograph of three women hanging posters on a building during the suffrage movement; this was a perfect jumping off point for the urban scene she would paint. As the images piled up, she began to see an opening into her vision. There was hope!

For the meeting, the committee wanted to see Hadley's design projected in situ to satisfy their concerns about scale and proportion. With paper, she created a five by ten foot mock up divided into the five sections onto which they'd be able to project images. The day of the meeting, she loaded her car with the mock-up, her pile of images, and eight new drawings. She felt almost like the old Hadley, productive and prepared to impress. Still, she would remain cautious until she could read the reactions of the committee.

The roads to Helena were a mess from snowstorms. The usual 1-½ hours drive took her 2 1/2 and it was white-knuckle all the way. By the time Hadley arrived at the State Capitol, she was so stiff she could hardly get out of the car; this was one of the few times she knew there would be no hiding her condition. After hauling all her materials up to the third floor of the Capitol building, she had to recruit the committee to help her hang the paper mock-up. They were supportive and happy to help.

Hadley held her breath as she walked away to view the mock-up from across the stairwell. She turned and knew immediately that the mural was going to be everything she'd hoped for. When the others saw the layout with scenes projected on it, they were as excited as she was. Together, they went through the images Hadley had culled and the conceptual and visual pieces began to form a coherent and compelling vision of women as community builders. Hadley was elated to get the green light to move forward on the murals.

At home in her upstairs studio, she prepped the two 5 x 10 foot powder coated aluminum mural panels, sanding and then brushing them with two layers of gesso to create a more textured, uneven surface. Then, she drew the borders that defined the center ovals, triangular corners, and outside edges of each panel. She used a computer-generated template for these so the dimensions and curves would be accurate; for their design, she borrowed the details of the Capitol building's interior moldings. She made transparencies of the 11 x 14 inch detailed pencil drawings she'd created for each mural so that she could project the images at a larger size onto the panels. Then, she began the long process of drawing, stopping as she went along to correct proportions that were inevitably sometimes off.

Because she populates her murals with many figures, Hadley often uses live models and a camera. In spring, when the Missoula skies had cleared, Julie Cajune, the Native American member of the mural committee, took Hadley to the Flathead reservation, home to the Salish Kootenai tribe. Julie had arranged for friends to pose for Hadley so that she could photograph them in authentic Native American clothing and accessories. One wore a buckskin dress and braids decorated with traditional "otter wraps," one carried a cradleboard, another rode a horse. Hadley positioned her models for a scene in which two women would be trading blankets and another that would illustrate the granting of Native American citizenship rights by the Indian Citizen Act of 1924. In addition to establishing historical authenticity, the photographs helped Hadley to accurately represent natural head angles, gestures and the drape of fabric. On one of her favorite days during the mural project, Julie took her and Sarah digging for bitterroots so they would experience this piece of history that would be included in the mural.

When Hadley transferred the drawings to the panels, the larger scale created empty spaces she needed to fill. She researched artwork and objects to decorate walls and tables, making sure every detail of a room, including lamps, rugs and curtains, was historically accurate. Often, she referred to old Sears and Roebuck catalogues for furnishings. She studied hairstlyes and obtained swatches of material from every decade from a historian of fabrics in Bozeman, Montana so that clothing would be appropriate. In outdoor scenes she was careful to be seasonally accurate when choosing flowers in bloom and produce being harvested or sold in the marketplace.

The Women's Mural Project committee made a studio visit and everyone had a thought or two about something a little different they'd like to see, but at the end of two days of discussion that generated a few changes and some compromises, everyone was satisfied. The project had hit a major turning point. Finally, Hadley could dive in with her paintbrush and bring to life the colorful history of Montana's women.

Find all episodes of An Alert, Well-Hydrated Artist in No Acute Distress here.