A serial about two artists with incurable neurological disease sharing fear, frustration and friendship as they push to complete the most rewarding creative work of their careers.

Read Episode Thirty-One: Parkinson's Comes Home. Or, start at the beginning: An Illness's Introduction. Find all episodes here.

In the year following Hadley's November 2013 multiple system atrophy diagnosis, I often contemplated the nature of our friendship. During the previous two years, we'd bonded over our weird neurological symptoms and been collaborators with the clear mission to find her a diagnosis. We enjoyed a dynamic partnership in which we analyzed the research Hadley had uncovered and the details of her medical appointments. When uncertainty chilled us, we stood together and pulled a virtual blanket over our shoulders, the way friends do.

Now that her medical mission was complete, Hadley was eager to stop being a fulltime patient and get back to being an artist. Even if she'd wanted to take time to reflect on her new health status, her mural commissions made that impossible. She'd moved directly from a marathon to get a diagnosis to a marathon to create the Montana Women's Mural.

Once an active texter, Hadley pulled back from her phone and email. I was reluctant to contact her much as I knew that with her workload, every minute and each pulse of energy counted. I also worried, since I was writing about her, that probing questions about her symptoms might sound to her like research rather than genuine concern. During our infrequent phone calls, I tried to discern from the strength and tone of her voice how she was feeling physically as she talked about the challenges of the mural project.

Hadley's insecurity about whether she'd been a reluctant choice for the mural commission continued to haunt her throughout the winter and spring of 2014. While she had strong support from several of its members, a few off-hand comments by others had hinted there was some concern about her skills, especially when it came to painting people. Encumbered by her wavering confidence, she labored through the mural's design phase into the spring. She knew when she showed the committee her design drawings at the end of May, she would assure them that when the images were enlarged, details would appear much more refined. But the truth was, she was noticing changes: a decline in her ability to organize material, process information and work with her usual speed and efficiency, which made her question her own assurances. These are all manifestations of brain changes typical in MSA. Up to 49% of MSA patients experience executive dysfunction due to the atrophy of many different areas of the brain, as well as difficulties with problem solving, flexibility in thinking, attention, and working memory.

"Not knowing if I can pull this off is eating away at me," Hadley told me. "This will be my last big project and the thought that I might somehow feel shame about it is pretty terrifying."

I felt anxious for her, worried she'd lose the courage and energy to follow through on the Women's Mural Project. Maybe it was too easy to project on her my own disease weariness and discouragement about my agent's inability to sell my novel. I should've known better; Hadley exemplifies the proverb: "When the going gets tough, the tough get going." She's full of surprises and the last thing I expected was what happened next.

"My friend invited me to have a two-person exhibition of our paintings in June," she told me one day in May. In my head, I jumped to the conclusion that she'd be showing paintings she'd done previously, but she added, "I'm having fun making all this new work for it."

I gasped. How could she possibly take on another project? I think my words to her were, "Are you crazy?" She laughed, which seemed like further proof that she was losing it.

When I began writing about Hadley in 2013, I hoped the process would help keep us close. But you risk losing something when you make someone's life a story, attempting to describe their individual struggle with language that will resonate universally. You have to stand at a distance, far enough away to see that person clearly. What I really wanted was to sit across a table from Hadley, to talk over coffee and poke our conversation into all the little crevices we didn't access on the phone. Not a day went by that I didn't think or write about her, but I was missing my friend.

In June, I flew to Missoula. My first day there, Hadley gave me a tour of her light-filled house and spacious studio, tucked under the steeply pitched roof. A thrill rippled through me, looking at the almost entirely empty Women's Mural Project panels that I knew, within months, would be filled with life and hang prominently in the Montana State House. Then I headed out in the car with Hadley, her husband, John, and daughter, Sarah, for a tour of Hadley's murals in downtown Missoula.

Surrounded on all sides by mountains, Missoula has all the best qualities of a small city: economic stability; an authentic main street that hasn't been cheapened by the tourist industry; a university that infuses it with energy, youthfulness and at least a little diversity; charming, tree-filled residential neighborhoods. The city has ready access to wilderness and a wide river that runs through it--always a five-star feature. After one of the coldest and snowiest winters on record, Missoula was buzzing with activity on this postcard-perfect, 75-degree day.

Driving to the murals' various locations, parking and re-parking could've been a problem, but (I noticed somewhat woefully) swinging from Hadley's mirror was a disabled person's parking placard. We climbed out of the car and I immediately saw the "cage" in which Hadley had described being trapped: her knees didn't naturally bend when she walked, so she lumbered, stiffly rocking from side to side. Her shoulders and neck were rigid too, as if connected by tendons of wood, and all of her movements were small and slow. My medication had kicked in and I was "on," my gait smooth, but Hadley is never "on," so we ambled down the sidewalk at the pace she set. I was reminded of the walks I took with my father late in his life, except this time, I wasn't feeling like the patient daughter. Instead, I silently railed against the disease that was taking away my young friend's ability to put one foot in front of the other. Tailgating that anger, of course, was my fear about my own walking future.

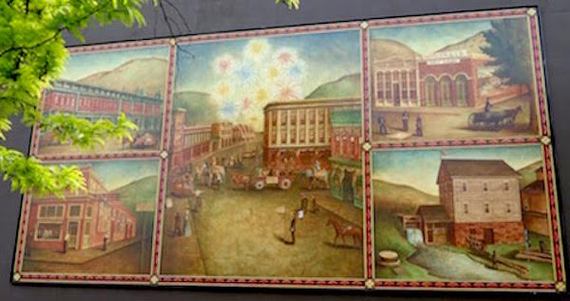

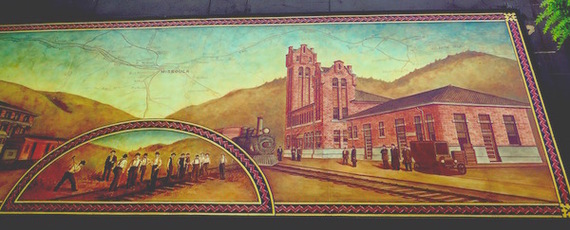

At the corner of Higgins and Broadway, we stopped so I could gaze at Hadley's seven-panel Heart of Missoula Murals, which cover 2400 square feet of the Allegra Print and Imaging building's exterior. The murals depict the development of Missoula's railroad, the founding of the University of Montana, and the city's industrial beginnings in the early 1900's.

Completed when Hadley was just 28, the murals were one of her first public projects in Missoula. I was amazed by how much she'd packed into them-- much more than anyone could take in just walking by. As I stood admiring them, a car honked boisterously. "Check out those awesome murals!" someone yelled, and I turned to see a woman leaning out the window of a station wagon. Hadley laughed -- the woman was a friend. Hadley is one of Missoula's treasures, I realized; she would be well taken care of.

We ducked into a bar, a bookstore and a juice bar to check out Hadley's other murals. Each of them uniquely fulfilled the vision of the shops' proprietors, showcasing the breadth of her capabilities. But the main event for me would be the murals she'd been creating for the Missoula Catholic School Heritage Project inside Loyola Sacred Heart School. A 2010 photograph of them on our Parkinson's Facebook page had been my introduction to Hadley and I couldn't wait to see them.

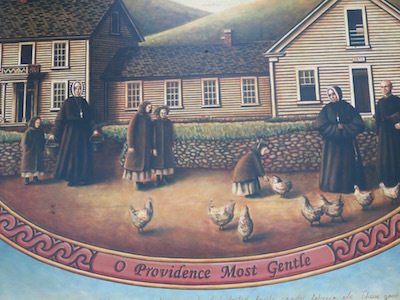

Since it was Saturday, the school was closed and we had the whole auditorium -- once a church nave -- to ourselves. Sarah had spent so many hours there with her mother that I imagined she'd memorized the murals; now, she careened around the voluminous space, shaking off excess energy. Three of Hadley's 12-foot tall murals hung on the east wall of the high-ceilinged, but otherwise architecturally unremarkable room, lending it tremendous warmth and interest. I couldn't help thinking about the long history of Catholic arts patronage as well as the glorious stained windows that have for centuries brought life to many a somber house of worship.

Hadley's murals, populated by priests, nuns, missionaries, children, chickens and horses, painted against a backdrop of Montana's glorious mountains and big sky, chronicle the work of the Jesuits in establishing in Missoula a "Catholic Block" consisting of three schools, a church and a hospital. Hadley had collaborated with the Missoula Catholic Schools historian, who'd researched the history of the schools for almost a decade. The more I looked at the panels, the more awed I was by both the dizzying amount of work and the high degree of skill they represented. Hadley's compositions are carefully balanced to form an architecture that pleases the eye. Yet, they're never static or predictable. She's crammed a Wikipedia's worth of history into the scenes but has made them appear uncontrived.

Hadley's murals, populated by priests, nuns, missionaries, children, chickens and horses, painted against a backdrop of Montana's glorious mountains and big sky, chronicle the work of the Jesuits in establishing in Missoula a "Catholic Block" consisting of three schools, a church and a hospital. Hadley had collaborated with the Missoula Catholic Schools historian, who'd researched the history of the schools for almost a decade. The more I looked at the panels, the more awed I was by both the dizzying amount of work and the high degree of skill they represented. Hadley's compositions are carefully balanced to form an architecture that pleases the eye. Yet, they're never static or predictable. She's crammed a Wikipedia's worth of history into the scenes but has made them appear uncontrived.

The murals' animated figures are full of life and character; you can almost hear their deep conversations, their music, chatter and laughter. Tonally, the paintings are quiet and have an earthy quality achieved by the use of an underlayer of sepia, which Hadley uses to ground and integrate the many colors she layers on top.

A fourth panel that hung on the west wall was in the "sepia stage" waiting its turn in Hadley's queue of commissioned work. Fortunately, the Catholic Schools mural committee had kindly agreed to put work on the murals on hold until the Women's Mural for the State Capitol were finished.

A fourth panel that hung on the west wall was in the "sepia stage" waiting its turn in Hadley's queue of commissioned work. Fortunately, the Catholic Schools mural committee had kindly agreed to put work on the murals on hold until the Women's Mural for the State Capitol were finished.

"Is this the last panel you have to do?" I asked Hadley.

She groaned. "No. Follow me."

We walked to the foot of the auditorium's stage, where the curtain was drawn shut. She lifted the corner of the velvet, revealing a tall scaffold on the stage. Behind it stood two more 12-foot-high panels. The panels were totally white. Huge, blank and full of expectation, of possibility and uncertainty. They were unfinished business in a life that would be unfinished.

I looked at Hadley. Her face had begun to take on the blankness of the panels, a hallmark of our diseases.

"I know," she said. "Don't even say it."

Hadley's art show opened the next night as part of Missoula's monthly "First Friday," when galleries in town are open late. Incredibly, in two weeks time, she'd completed fifteen new paintings, most of them quite small, for the show. I helped her deliver the paintings -- some still wet -- to the gallery space, where she finished framing some of them. It was clear she'd had a lot of late nights. I couldn't imagine how she was going to hold up for the three-hour opening that evening.

She didn't just hold up, she held court with spunk and grace. Many friends, colleagues, her mother and her doctor were there to admire her often pastoral, sometimes dramatically lit landscapes of Montana, Nebraska, Czechoslovakia, and the Oregon coast. Quite a few of the paintings demonstrated Hadley's interest in exploring the sky's limitless possibilities for shape and color.

By the end of the night, Hadley had sold twelve of the fifteen paintings. She was in high spirits and although I assured her I would understand if she craved going home to sleep, she wanted to go out and celebrate. So we did. She ordered her usual mojito. We didn't exchange one word about illness.

I'd thought Hadley was crazy to add the art show to her gigantic to-do list. Now, it was easy to see the magic the event had worked on her. For a few blissful weeks, she'd painted whatever she wanted -- more like play than work. The show was an opportunity to make some much-needed money, but even better, it had bolstered her confidence at a time when it was flagging.

Hadley related the art show experience to the physical therapy she'd been having. "Do what makes you feel successful," her PT had told her when she was having trouble with one of the exercises. The therapist modified the exercises so Hadley could do them without feeling frustrated. Similarly, Hadley's doubts about the looming, unfinished murals were offset by the pleasure and sense of accomplishment she gained by completing a new body of work.

Looking ahead at the next five months, she told me with a big smile, "The energy and spirit that went into the show gave me a huge boost. I want to try to keep that with me." That spirit, I knew then, was what I'd come to Missoula to witness. There would be ups and downs for sure, but Hadley would ride them out.

I had no doubt she was on her way to pulling off something spectacular.

Find all episodes of An Alert, Well-Hydrated Artist in No Acute Distress here.