A serial about two artists with incurable neurological disease sharing fear, frustration and friendship as they push to complete the most rewarding creative work of their careers.

Read Episode Thirty-Two: Blank and Full of Expectation. Or, start at the beginning: An Illness's Introduction. Find all episodes here.

My novel was not going to get published.

I'm sorry to have taken so long to read Catherine Armsden's fine and singular first novel, especially since I won't be making an offer for it. Her approach to the experience of going home after a long absence is utterly original, thanks to her training as an architect, but I'm afraid the novel as a whole was a bit too traditional for my somewhat peculiar tastes.

I very much enjoyed Ms. Armsden's deep and complex portrait of a middle-aged woman coping with familial loss, her living relatives, and the smaller everyday struggles of life. The relationships witnessed in the narrative felt fluid and natural, especially in the revealing of the past through Gina's journey back to Maine. And I especially loved how the house itself was treated as a separate character, with a personality of its own. Yet, despite its merits in capturing authentic familial situations and the visions of our pasts that remain imprinted in our minds and memories, I'm afraid I felt my traction with the emotional side of the narrative begin to slip a bit as I read on. While there were many heart-moving aspects to the novel, I'm afraid I just never lost myself over the whole so completely and totally that I would be able to give it the push it needs to succeed in such a tough marketplace.

It had been more than a year since my agent had sent Dream House out to publishers. The mini-reviews and "I'm afraid"s somehow made the rejection worse. (Look what a good job she did! She almost had me!) I was standing metaphorically naked and cold at their gates and they weren't going to let me in because they were, apparently, afraid. Every pessimistically leaning cell in my body was telling me that a traditionally published novel was not in my future.

In an unguarded moment, I indulged in some self-pity about this with my friend Sylvia. "Things could be a lot worse, Catherine," she told me crisply. I was duly chastened. Every optimistically leaning cell in her body was still fighting cancer. Chemo had been remarkably successful and she was feeling pretty well. It was July, and the next week, she'd be having a biopsy and high-frequency ablation that would hopefully get rid of a small lesion on her liver. I was thrilled that come September, she and her husband would be moving into a place just 3 ½ blocks from me. Also, I was actually, genuinely, afraid.

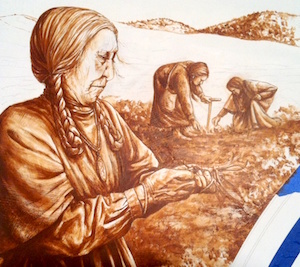

By July, the Montana Women's Mural Project panels were prepped, awaiting paint. Hadley's drawings captured the activities of Montana women as community builders during two time periods in the state's history. Panel one, titled "Women Build Montana: Culture," is set in 1898 and depicts ways in which Native American, Euro-American and Mexican-American women and children contributed to the state's culture and economy through their paid and unpaid labor and social engagement. Panel two, titled "Women Build Montana: Community," is set in 1924, the tenth anniversary of Montana women's suffrage and the year the right to vote was extended to Native American women. The mural illustrates Caucasian, Native, African-American and Asian-American women at work in civic and volunteer activities, business, politics, homemaking and education.

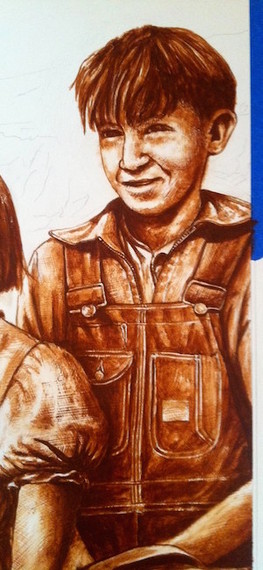

Four months: the time Hadley had to pour this rich, pictorial history onto the two five-foot by ten-foot canvases in her upstairs studio. She hunkered down with her brushes. To begin, she chose the top left corner of panel one because it was a section she felt wouldn't need design adjustments. She had pleasant feelings about the scene -- of a Native American digging bitterroot -- because of her memories of the day mural committee member Julie Cajun had taken her and Sarah to dig bitterroot on the Flathead Native American reservation. While they dug, Hadley and Sarah had delighted in Julie's stories about harvesting the root with her own mother, and the experience of discovering a ripe bitterroot and peeling away its bark.

Now, Hadley's paintbrush was poised above the canvas, ready to bring definition to the first of 33 characters that populate the two murals. As soon as the bristles touched the surface, though, she froze: What if this is the brushstroke that makes this figure look all wrong? she wondered. Can I really do this at all?

It wasn't so much her physical condition that was impeding her progress, Hadley realized, but rather, the festering anxiety that the mural committee was unsure about her capabilites. It would sabotage both the project and her wellbeing if she couldn't recover the self-confidence that had lifted her after her June show.

Hadley knew she couldn't afford to wait for reassurance to come from an outside source; it had to come from her. One day she hung a sign over the mural that said, "Just Do It!" Somehow, the sign was exactly what she needed to shut out the chorus of critics in her head. When she'd completed the woman digging bitterroot, she moved to the upper right corner of the panel, where two Mexican-American children are harvesting sugar beets. Finally, at the end of July, she described a shift in her outlook:

After working on the children, I had several days of photographing friends who posed for the next set of mural images. In one scene, I wanted to create the sense of a light breeze so I set up fans in a gymnasium that blew their skirts in a way that looked natural. We also spent a lot of time collecting images for several of the vignettes. In one corner of the mural, women are sewing a Montana flag so we gathered all kinds of vintage sewing items and I set them up as a still life and took photos for reference. We shared fun laughs while hearing the stories behind the items we'd collected. The positive energy generated by working with my friends on these photo shoots began to override my feelings of doubt. Working on the sewing corner of the mural after the photo shoots, I realized after a few hours that I was actually enjoying painting. This was a new feeling for me since starting the mural. I relished the slow pace and seeing each object come to life. When I painted the people, I felt their personalities come through, and instead of worrying about what a line might or might not do for a particular portrait, I just let it happen. The new pleasure I was feeling was very powerful. And here's the most powerful part of it all: this week, as each person has emerged on my canvas, I've felt like I have one more person in this with me. The scary white canvas isn't scary or lonely anymore. It's filled with life. The women I've painted have become friendly souls who surround and encourage me. The children smile at me and the women are laughing and talking together. This is an entirely new experience. I've never had this happen with any other painting. I can't believe that it happened with this particular project that has been such a struggle to get through. It feels like the ultimate mental and emotional achievement to move from such a desperate place to this place of enjoyment and security.

Along with her extraordinary bonding with the life in the murals, Hadley became more accepting of her physical limitations. She told me there were days when she pushed herself much too hard and she would simply stop, rest and hope the next day would bring her better energy. She was stiff and achy in her hands, neck and back. But she experienced a new self-compassion, especially when she noticed that her very slow pace allowed a keener attention to detail. Happily, the quality of the work was exceeding her expectations.

September -- two months until the November mural installation at the State Capitol Building in Helena to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Montana suffrage movement. Two months later, on January 7, 2015, a formal dedication would take place. Hadley painted twelve hours a day, setting a timer for 45-minute intervals so she could rotate between the School of Forestry murals and the Women's Mural Project. She hoped that dividing the time this way would help to keep up her energy. But she was panicked and fairly certain she wouldn't be able to meet the November deadline, despite working as hard as she could and sleeping in her studio from midnight to 4 a.m. She wrote to me:

My brain feels tired. I have such a hard time thinking, seeing the big picture, staying on task and focusing. Incredibly, the paintings don't show this. The images are looking strong. But the big clue that I'm struggling is that the amount of canvas that's covered is still minimal. I'm embarrassed to send you photos because I don't feel like I have enough new work done to warrant them.

On top of the mounting pressure she was feeling, a frightening new development nearly plunged Hadley into despair. Driving around town to pick up Sarah at school or do errands, she was misjudging distances and not noticing things in her peripheral vision, hitting curbs and nearly sideswiping parked cars. At intersections, she found she was having trouble processing all that was happening: traffic lights, cars turning in front of her, pedestrians in the crosswalk. Her reactions were too slow. At first, she attributed her bad driving to fatigue and stress. But the near misses began to add up and she worried that she was experiencing more cognitive symptoms of MSA. One day, she was horrified when she nearly hit a mother and child while taking Sarah to school. John and her mother, Jana, told her somberly they thought she shouldn't be driving anymore and Hadley agreed, though she hadn't prepared herself for this possibility. With her extreme rigidity and slowness, walking more than a block or two was not an option and driving had given her the freedom her disease was taking away. She was devastated about the independence she would lose. "I never cry," she told me. "But this hit me really hard and I've cried about it every night."

The next week, Hadley braced herself for delivering the news to the mural committee that she couldn't have the murals done by November. To her enormous relief, the committee, though disappointed, was understanding. They conceded that because they'd delayed the artist selection and held up the project during the first few months, the November ceremony probably had been wishful thinking. They were content to focus on the January 2015 unveiling.

The reprieve made Hadley momentarily lighter. Then, stepping back from the murals to assess the amount of white surface and color she still had to fill in, she was caught in January's blinding headlights, speeding toward her.

Find all episodes of An Alert, Well-Hydrated Artist in No Acute Distress here.