It was with an odd mixture of joyful anticipation and a bit of dread that I sat down to read my friend and colleague Yangzom Brauen's story of growing up as a third generation Tibetan woman in exile. You want so badly to be supportive of a friend's work, but you don't want to have to give them false praise. But I needn't have worried, as the book and the story it tells are both breathtaking.

If the story was made into a movie you might accuse the writer of taking too many liberties with the truth. How could a young nun and young monk marry as Tibetan Buddhists? How could their young daughter survive the perils of a dangerous escape through the snow covered Himalayas and go on to marry a dashing Swiss academic? And then their daughter becomes a thoroughly modern blend of freedom activist and gorgeous Hollywood starlet. It defies belief! But not only is the tale that Yangzom Brauen weaves of three very different yet integrally connected generations a satisfying read, I guarantee that you will learn more about the struggle for Tibetan independence, the complexities of the Tibet-China relationship, and the principles of Tibetan Buddhism than you will glean from any Westerner's account. If you value exceptional storytelling, I urge you to read this book. If you care about human rights, women's issues and world peace, you must read this book.

Yangzom has been touring with the book on her own, but for this interview I insisted that she bring her mother, Sonam, along as well.

Christal: I still can't get over is the fact that your grandmother and your grandfather were actually a monk and a nun. Can you explain how a monk and a nun would marry in Old Tibet?

Yangzom: There are different schools in Tibetan Buddhism. My grandmother and grandfather come from the Nima school [the earliest Buddhist tradition in Tibet] and there it's kind of okay to be married to a monk or a nun. It's not the best, but it just happened. She never thought about it while she was living in the hermitage for 13 years. Suddenly, there was this monk and he fell in love and she fell in love. And she never had that feeling before. So they both went to a Lama and asked him what they could do to, you know -- to overcome the bad karma. He said some prayers and that's how [it became] possible.

Sonam: They stayed forever as a monk and nun.

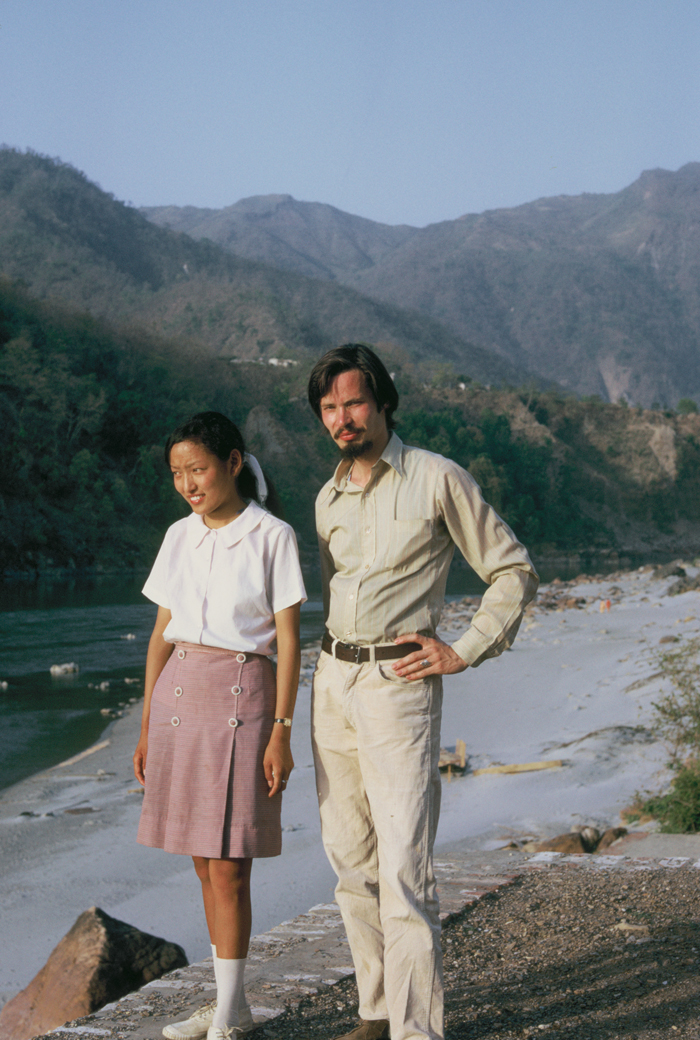

CS: That's incredible ... And, Sonam, you also were not looking for a husband and the man who found you -- He says that he fell in love with you at first sight.

SB: That's true. I was about 18 or 19 when I met my husband in India and I never thought about marrying or having a boyfriend. In my generation, at that time, we didn't used to have boyfriends -- like that.

YB: Plus a white man, too. He's not even Tibetan.

SB: I must be the first Tibetan who is having a boyfriend who is a white man. That's not counted as good. As Tibetans say we should marry our own. But if the fate is there -- you can't do anything.

CS: Well, it was a little bit of a fight for your husband, right? He had to actually get a letter from the Dalai Lama in order to marry you?

YB: Yes. He just felt he had to show everyone it is fine that my Tibetan mother can marry a Westerner and it's not weird because in the beginning it was hard for my mother -- But, I have to say, my grandmother was very open-minded for being a Tibetan nun from Old Tibet coming to India as a refugee. She really liked my father. She didn't care if he was Tibetan or not. She just went by her feeling.

CS: But, it changed her life dramatically as well. Because marrying you, Sonam, meant that he brought you and your mother back to Switzerland. What a huge change.

SB: Isn't it? That's true. Sometimes when I think about it, it's really fate because I didn't look for it. We didn't know where Switzerland was. We thought now we are in India and we'll stay there. We left our homeland and I didn't want to go anywhere else.

YB: And, now Mola [grandmother] says Switzerland is kind of her Paradise.

CS: I want to talk a little about the notion of femininity because with each generation it was such a different thing. That's true in all families of course, but more so because we're looking, first, at a nun and her unconventional marriage which is dwarfed by how unconventional your marriage was, Sonam. Yangzom, for your grandmother one of her first interactions with a western male was when one of the Swiss members of the Red Cross in India carried her bag for her, because it was heavy. For her, this was a shock. Women are not treated this way in old Tibet. Each of you in your generation, has had such a different experience of being a woman, of being feminine and yet, you all understand each other.

YB: My grandmother, she really prays, for example, that in her next life she is going to be a man. For her, and her beliefs as a Buddhist, a man is a better rebirth than a woman because we have menstrual pain. We go through birth and pregnancy. There is so much, actually, which is all looked at as bad and un-hygienic -- you're not allowed to walk over rivers or go into sacred places when you're having your menstrual period. My mother and I, we kind of enjoy being a woman. So, my mother suddenly marries this Western person and comes into this First World where women have the same rights as men. I think that changed my mother's mind. I grew up in the First World. For me, it's clear. Women have their rights. I also find, if someone carries my bag, I'm not astonished about it. Especially if it's a man, it's kind of normal. And, for my grandmother, still not.

CS: And, also again, looking at Mola, if I can call her that. She has the short hair of a nun.

She's probably never worn makeup in her life. She mostly wears her robes. Is that correct?

YB: Always.

SB: Always.

CS: And then, you jump a generation, and you've got Yangzom, who is young, attractive, sensual. That's a different kind of femininity.

YB: It's very different and my Grandma does see those pictures and she always came to every play I had and watched my movies. But, then, when there's a kissing scene or something she's like, "Agh!: and she can't watch that. But, she does pray every day for me. She asks that I get a job as an actress and when I talk to her, the first thing she asks is, "Did you get a job?" Even, if she doesn't understand exactly what I'm doing, she knows that's my destiny. I always wanted to be an actress since I was six years old. And she knew when she was six she wanted to be a nun. So, she says it's my karma and she does accept it and embrace it.

CS: Sonam, you're an artist and that's something that came much later for you.

YB: I think, maybe, if my mother would have grown up in Switzerland in the beginning, she would have become an artist sooner.

SB: Especially as a woman. In my generation, I think there is nobody who is an artist as a woman, and I have a feeling the woman belongs to the kitchen and to look after children and these feelings I still have sometimes. "I'm not so good. I'm not a man. A woman can't do that." Sometimes it comes back to me even if I know it's not true.

CS: Sonam, the book begins at a crucial moment during your escape from Tibet to India over the Himalayas and you fall down a crevice in the icy snow and we don't know until much later in the book how you managed to get out. You were with a large group of people, and what struck me most was the fact that once you caught up with your mom you didn't even tell her immediately what had happened to you, how you were almost left behind forever. You didn't tell her until that night.

SB: That's amazing isn't it? And, I have such a clear [memory] of this -- I will never forget it. You were never allowed to cry. You have to be quiet and walk and walk. We were all afraid, but you have to survive. So there's not time for such things.

CS: So, you nearly lost your life but you didn't have time to tell anybody about it because everyone was fighting for their lives at the same time?

SB: Exactly.

YB: And Mola really couldn't remember. It was so long ago and so far away. My grandmother lives so much in the present and not in the past. Even when we tried to get her parents names or her husband's names or her kids who passed away. She said, "First of all, I have forgotten and second of all, we're not allowed to say those names because they passed away and you should let the death be so you don't bring them back here." That was very interesting for me too. I would never forget my mother's name. No one would. For her, it's not - there is no point and it's not important. So try to be as much as possible in the present. And, I think that's probably why you never told her.

SB: Yes and there were so many other problems that came up -- my sister died and my father died and we were struggling all the time. Things which happened -- happened. I forget -- I just leave it [behind].

CS: Now is that your Buddhism or just part of aging?

YB: It's [about] not holding on to things. I think it's why my mother and my grandmother are still today very happy people. After you read their book you're kind of amazed that they can be so together and so happy -- It doesn't have to be Buddhism, but I think that if you believe that this is my karma and to accept it even if it's really hard and to say, "Okay, that's my life."

CS: But for you, as a third generation activist, isn't it all about not accepting the status quo?

YB: I won't accept that Tibet is occupied by the Chinese and I'm sure my mother and my grandmother don't either.We want to do something so that Tibet gets its independence again. Even if it's small, little things we do. At least when you do something, something can happen.

CS: The book was first published in German and now it's in French, Italian, Finnish, Estonian, Dutch and finally, English. So, what kind of feedback have you gotten so far?

YB: I get emails or Facebook messages from all over the world and people really love to read the story of three generations of Tibetan women through three continents. They're very much impressed about my grandmother's and my mother's life -- how they grew up. My life is more similar to their life, so it's not as interesting but the interesting part is to start thinking about their own grandparents and what their family history is.

SB: They are so amazed at how we went through such amazing difficulties. And, now my mom is a very jolly person. She makes jokes and laughs. You would never think that she lost so many things.

YB: And, because she's always wearing her Tibetan chupa and has her short cropped white hair she says, "Yeah, people say hi to me." Even though she doesn't really speak German, she can say hello in German and they just start talking. She always has visitors at her place. They come for tea because she invites them for tea. And, it's very cute to see -- without words how much love she can give them.

CS: But that's actually how it started, how she communicated with Martin, your husband and dad respectively, right?

SB: Exactly.

CS: It seems like they have such a bond, such an understanding and I'm trying to imagine how that can happen if there's no conversation. How does that work?

SB: My husband was a very pale-looking young man traveling in India. He was very thin because some Indian foods are very spicy and my husband at that time couldn't eat much. So my mom saw this and she felt pity for this young boy traveling around. She would cook [him] noodles without spices and that is how they got to know each other. They even traveled together in India. Without talking they got to know each other.

YB: My grandmother was about 40 when she came to Switzerland and she felt that she's too old to learn another language. And for a Tibetan, 40 was really old. So they use sign language and jokes. They know each other so well.

CS: When someone finishes reading this book, what do you hope that they will feel?

SB: I hope that actually people will see that Tibet is occupied still. Still we are not free. This is the most important thing which I would like to inform people. People that are living there -- they are not free. They don't have the freedom of Speech. If they want to practice their religion, it's very difficult. One has to be careful. Through this book, my most wishes are that the whole world finds out that Tibet is under China, that we are suffering. So, this book, I hope with this book, people start to think a bit. That's my wish.

CS: The Dalai Lama read the book. I feel like Mola has him on speed dial. He's come into your lives at many points, especially for your marriage. Tell me about his reaction.

SB: He says that our story is the same story that every Tibetan has experienced.

YB: All the Tibetans I know in Switzerland tell this exact same story about how they ran away. But [ours is] the Tibetan story told in three generations of women. What I found out with a lot of male readers, [they say] " It's not just for women." So, I think it's interesting to hear that. It's for everyone.

SB: Everyone.

You can hear my full interview with Yangzom and Sonam Brauen on The Tibet Connection's December program