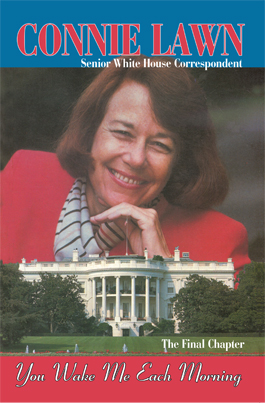

This post is excerpted from Connie Lawn's You Wake Me Each Morning: The Final Chapter, published by iUniverse.

This post is excerpted from Connie Lawn's You Wake Me Each Morning: The Final Chapter, published by iUniverse.

It was the summer of 1968, and I must have looked strange, even by sixties standards, in my gleaming white hard hat with a steel antenna swaying from its crown. I was the only field reporter covering Resurrection City. This huge demonstration, built by several thousand poor rural blacks who wanted to raise the consciousness of Americans to their poverty and lack of real job opportunities, was situated on the picturesque Mall in the heart of Washington, D.C. I was reporting from Resurrection City for WAVA was then the only all-news radio station in the D.C. area. it was probably the first all-news station in the world. In those days, to transmit live to the base station, I carried a mobile unit weighing 50 pounds; the hat and antenna were part of the outfit.

The huge tent city built by the poor had become a sea of mud, nestled between the Washington and Lincoln Monuments. So rubber hip boots were my wardrobe accessories, despite the fact that it gets pretty hot on a Washington summer day. The paraphernalia I carried became increasingly heavy as I sloshed around in the muck, so I asked some of the "brothers" to help me carry the equipment. I even promised them: "If you're nice to me, I'll let you fondle my antenna."

They weren't particularly tempted by the prospect of a lust-crazed antenna, but they were in fact extremely helpful to me. I was, incidentally, one of the few white reporters spared a dunking in the Reflecting Pool, which was in the center of their encampment.

The "city" of several thousand poor blacks was policed by the Tent City Rangers of Chicago and other militant gangs from across the country. In fact, the gangs were so tough that several branches of the local police (District Police, Park Police, Capital Police, and so on) were nervous about setting foot inside the crowded, muddy, bug-infested compound. But no one ever threatened me, or attempted to molest or harm me. That's more than I can say about a lot of politicians on Capitol Hill, or news directors I've known in nearly forty years in this business!

I did have a close call one night, however. I was scheduled to leave Resurrection City each night at 5:30, crossing Memorial Bridge to lily-white Rosslyn, Virginia, to deliver a "wrap-up" on the day's activities. One night, my "hosts" decided I'd learn more if I spent the night with them. I tried to convey this subtly to my news director, Pete Gamble.

ME: "This is Mobile Unit K I Y 549 calling Base Station."

HE: "Where the hell are you? You're late for your [expletive deleted] report."

ME: "I'm a guest of the bosses at Tent City."

HE: "You'll lose your job if you don't get your ass back here."

ME: "I'm having a great time and can't leave."

HE: (after a long pause, and in a voice the whole encampment could

hear)"Are those goddamn hooligans keeping you prisoner?"

At that point, one of the muscle-bound Tent City Rangers grabbed the microphone and gave Pete a tongue-lashing in words neither of us "honkies" had heard in our whole life.

The moment passed, and I spent what turned out to be a harmless if somewhat muddy night with thousands of impoverished demonstrators from across the country. My initial wariness became outright terror when one of the Rangers hurled me into a tent. I braced for the worst, but it never came. Most of the demonstrators treated me with respect, and were much more focused on talking to me about their grievances and the suffering in their lives than they were in harming me. We spent the night in conversation, and I learned more about black society in those few short hours than I ever had growing up in a racially mixed town and attending a rough, integrated school system.

The plight of the campers was indeed tragic, and I believe their demonstration did much to focus the country's attention on their problems. But little of that sympathy was evident when the local police forces managed to shut down Resurrection City a few weeks later.

That happened on the day the men and boys marched up to Capitol Hill to demonstrate and lobby their Congressmen. This gave the police an opportunity to move in and gather up the women and children. In some cases, billy clubs and tear gas were used with grim determination, in violent assaults rivaled only by the U.S. Cavalry against the Indians a century earlier.

I almost missed the bloody closing of Tent City. Earlier, I had parked my car in a motel parking lot across from the WAVA studios. When I went out to retrieve it, I discovered that the police had towed it away. In my frantic rush to get to the scene of the action, I flagged down a businessman commuting to work on a motorcycle and insisted he give me a ride. What a sight we were - he in his business suit, clutching an attache case, me looking like some avant-garde Martian in my hard hat with steel antenna, hip boots, and mobile unit. Nevertheless, the police - no doubt rendered temporarily stunned by our audacity - let us cross the lines at Tent City.

Two days later, after it was all over, I went back to Rosslyn Virginia, located my car and managed to steal it from the police lot. I had an extra set of keys, and simply drove my car over a log which served as a barrier. Surprisingly, I never heard from them again, and never paid a fine.

By that time, of course, the police had on their minds a lot more than my repossessed car. Washington and its suburbs again were erupting in racial warfare. In fact, the policemen's rage against Resurrection City was partially a reflection of the pent-up anger they harbored against many of the blacks. These incendiary elements had simmered since the aftermath of the April 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. It was a scary time, when major riots exploded in many American cities. Washington was among the hardest hit. Sporadically, over the seemingly endless summer, minor uprisings developed. I found myself in the midst of one - perhaps I was even the cause of it.

The trouble began at 14th and U Streets, an area in the center of the black ghetto, which was the wellspring of many local riots. The corner had become a gathering place because the offices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or SCLC, were located there. When sparks started flying, and the simmer threatened to escalate to a boil, my news director sent me to 14th and U. I reported live from the location, noting that an angry cluster of people was milling about, eager to stir up some action. I was concerned the broadcast would exacerbate the situation, which it did.

Within minutes, the group had swelled to to twenty, then thirty, and then into the hundreds. I definitely stood out, with my white skin, red hair, and antenna. About that time, the charismatic black civil rights leader, Jesse Jackson, arrived on the scene. This was years before he would become the first major black Presidential candidate, but even then he could mesmerize and control and audience. He stood up on a truck, and began his hypnotic chant: "I am ... a MAN ... I am SOMEBODY." Hundreds joined in and were broadcast live on our radio station, WAVA.

The crowd continued to boil, as did their sense of power and anger. Finally, Jackson realized my presence was making the crowd grow larger and madder. He glared down at me from the truck and announced, "You goddamn bitch, you're making it worse!" He then had me picked up and thrown bodily into the SCLC headquarters. From my vantage point inside the building, I had a clear view of the violence and rioting which ensued. Unfortunately, I made the situation worse by continuing the broadcasts; a consequence which is an inherent dilemma of my profession. In any case, by expelling me from the demonstration and banishing me to that building, Jesse saved my life - whether he meant to or not. For that, I will always be grateful to him, regardless of whether I agree with his philosophy, or with the scandals which later engulfed him, such as having a baby out of wedlock with a young assistant who was not his wife.