Where would the Arab spring be without Facebook? Twitter? YouTube? Phones with digital video? The Square, an edge-of-your-seat documentary on Egypt's uprisings, is testament in style and substance to the game-changing role technology has come to play in revolutions.

The Square won an Audience Award when it premiered at Sundance early this year and a People's Choice award at the Toronto Film Festival. With footage starting in Cairo in January of 2011, The Square takes us through the resignations of both Hosni Mubarak and Mohamed Morsi. Though the ousters were supported by millions of Egyptians, the main action of the film takes place in Cairo's Tahrir Square.

Filmmaker Jehane Noujaim's bi-cultural background (she was born in Washington, DC, raised in Kuwait and Cairo, then returned to the US for Harvard) lends her a passion for the social upheaval as well as a distance. She portrays the desperation of a people who cannot tolerate the old regime any longer but are not yet ready with a viable alternative.

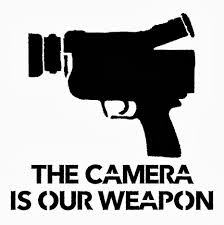

Gritty and compelling, the film's cinema verité style underscores the turmoil it portrays. Hand-held cameras and smart phones document action from the thick of it, taking us into the streets where swarms of protestors collide with the military police- we see chanting, rioting, beating, and tazing, right in front of the lens.

Noujaim presents the issues through a selection of activists with varying views on how to free the country from corruption and poverty. They speak to the multiplicity of attitudes, to the complexity missing from simplistic CNN reports.

Ahmed Hassan, the main narrator and revolutionary, was a poor kid from Cairo who sold lemons in the street to pay for his schooling. We follow his story over the course of two years, through fervent wishes and dashed hopes to an ultimate belief in a future victory.

Ramy Essam is a singer/songwriter and political activist who composes and performs ballads of the revolution, and gets a brutal beating from the military police. Yet he sings on, playing a comparable role to the anti-Vietnam folk singers of the 1960s.

Magdy Ashour is a member of the Muslim Brotherhood who doesn't agree with them about much, particularly when they make a deal with the army to stay out of Tahrir Square in exchange for elections, which they win by a scant 51% over the old Mubarach regime.

The Square also features Khalid Abdalla, Egyptian actor and star of The Kite Runner. He tells the camera that for three years he has spent a lot of time in Tahrir Square, lending his voice and influence to the revolution. Born in Glasgow, Scotland, to Egyptian parents (both doctors and dissidents) who emigrated in 1979, Abdalla is a global citizen, schooled at Cambridge in England and fluent in Arabic, English and French. "I'm proudly British and proudly a Londoner, but I'm also proudly Egyptian and proudly from Cairo."

Throughout the film, laptops are everywhere, along with digital cameras. Smart phones seem the revolutionary's stock-in-trade. Collectively they document the revolution as it happens, recording demonstrations in Tahrir Square with an armed and armored military police advancing on citizens. The activists' telling footage is spread in instant replays on the wings of the Internet.

As anyone knows who watches Jon Stewart and his revealing juxtaposition of clips, cameras are great at catching up people, thwarting their attempts to rewrite history. Recordings allow assertions to be paired with actual events, which often stand in stark opposition. Before video, opposing claims were reduced to a matter of hearsay, but current technology allows reality to be irrefutably captured and circulated for all the world to see. It's easy to understand why totalitarian China restricts access to the web.

The film shows a military official in Tahrir Square telling protestors, "The army will sacrifice their own blood before firing a single bullet on the people. Now please collect your things and go home." Later we see raw video of protestors run over by the army's tanks, their lifeless faces crushed and misshapen. Ahmed is visibly shaken. "It was war in the square, not a revolution. The army betrayed us. They are killing their own people."

The Internet seems the world's great equalizer, the best medium for spreading information and ideas since Gutenberg invented the printing press. For anyone anywhere with access to a computer and open reception, it is impossible not to know there are options in how to live.

The Square is an unsweetened but optimistic portrayal of a society in flux, thanks in large part to the egalitarian spread of digital data. Taking a further step on the tech highway, The Square will be streamable on Netflix in early 20014. With a window onto freedom, there is every reason to hope that the remarkably resilient Egyptian people can achieve a more equitable government.