It's oh so tempting for the mainstream media to give what's happening in Egypt a pithy label, and for a new media scholar like myself, I would seem to have a vested interest as well, but if I have learned anything through my five years studying cyberactivism in Egypt, it is that revolutions don't happen in cyberspace, they happen in the streets.

Hundreds of thousands of people from all walks of life across wide swaths of the country of 80 million people have taken to the streets, demanding political change. Twitter, SMS, and Facebook were certainly crucial tools used by activists to mobilize and communicate, but they were not the cause of the protests or the raison d'être.

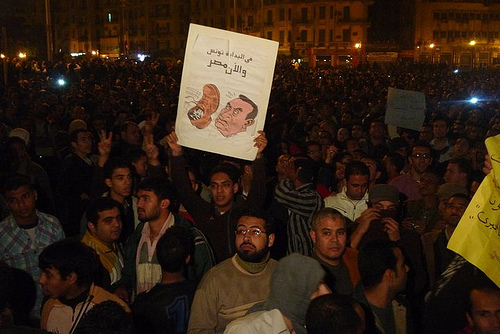

Picture courtesy of Al Jazeera via Creative Commons license

Picture courtesy of Al Jazeera via Creative Commons license

But I have to think it was the successful toppling of Tunisian president Ben Ali that inspired the downtrodden and economically beleaguered citizens of Egypt who don't have smart phones or Facebook accounts and took the protests from the digital realm to the reality of the street, where tear gas and rubber bullets make it a far more significant commitment to support the protests than clicking 'like' on a webpage.

In 2008 the April 6 movement made an attempt to link digital activism to a broader public, but it largely fizzled because it did not enjoy broad public support because the valiant digital activists couldn't get their message to the street. Today was of course not the first time Egyptian have taken to the street demanding political change, but it is the largest in many years (bigger than Mahalla, April 6, the judges demos or even the Iraq protests). 56,000 people signed up for the Facebook page within the first 24 hours and the Twitter hashtags #jan25, #Egypt and #Mubarak were all worldwide trending topics today. As Egyptian blogger-activist Zeinobia so aptly noted, "who said that people only revolt thanks to social networks !!? As far as I know there was no social network in 1919 or in 1977 !!??" But that's ok, because digital activists and especially those in the Middle East and other Western-supported authoritarian regimes, depend on the mainstream media to get interested and amplify their message, partially in order to put pressure on Western politicians back home (as I have written about before).

Nonetheless, the government's decision to completely block the Internet and shut down mobile phone services is a new development in the regime's repertoire of repression. Blogging, texting and social networking have been key tools for digital activists struggling for political change at least since 2005, yet this is the first time Mubarak chose to completely strangle the telecommunications infrastructure (I remember when the internet went down in Egypt for a day in 2008 and everyone thought it was a plot but it just ended up being a problem with an underwater cable). According to one analyst, Egyptian authorities blocked individual adopted "a very careful and well-planned method to screen off internet addresses at every level, from users inside the country trying to get out and from the rest of the world trying to get in," namely at the DNS and the ISP levels. Individual social media sites including Facebook, Gmail, Twitter, and others were also blocked, though many enterprising digital activists managed to circumvent the block by urging people to leave any working wifi connections unlocked and using good old landlines to get their information out.

Cyberactivist stalwarts Manal and Alaa put up a useful how-to on Manalla.net for using landlines to connect to international ISPs through good old dial-up connections while the Tor network urged supporters around the world to join the virtual proxy cloud. The authorities also pressured Vodaphone to cut service, which the company did. Nice way to support freedom of expression, Vodaphone!

But despite all the government's attempts to restrict the power of digital and social media to organize, mobilize and galvanize, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets. One needed only look out the window to see the streets of Alexandria, Cairo, Sharqiya, Suez and countless other cities in Egypt flooded with protesters who managed to push back police trucks, throw back tear gas containers, and in at least 5 cases trade their life for the hopes of their country. I personally had to follow the protests from afar, glued to Al Jazeera English on my iPhone and Twitter on my computer. I recommend following Alaa, Mina Zekry, Wael Abbas and Sarah Carr. If you don't read Arabic, here are a few good English-language blogs to follow (and you can also check out the blog rolls of Egyptian activists at my Arab Media blog): egyptianchronicles.blogspot.com, bikyamasr.com, baheyya.blogspot.com/, www.arabawy.org/. There are many others but that's a start. Because even if this isn't a revolution attributable to new media (or WikiLeaks, as some pundits attempted to label Tunisia's remarkable overthrow), it is one in which digital and social media are fundamentally shaping how the outside world sees it.