The term codependency comes out of the recovery movement with the reliably frequent observation that unhealed families tend to unconsciously subvert the newly-achieved sobriety of addicts. Recovery is not solely a matter of individual healing: Every interaction in a family damaged by the abuse must now change, which is difficult and scary.

But codependency involves more than a fear of change. Rather, it refers to the subtle (or not so subtle) encouragement of people's dependency on oneself. The codependent seek the company of the needy, the bewildered, the at-risk, the mentally ill: those with a wing down. Someone to help.

As a psychotherapy client who worked in real estate once admitted to me about her series of unhappy relationships, "I like my partners like my houses: fixer-uppers." As soon as she "fixed" them she lost interest and moved on, nor was she attracted to capable and centered people not in search of salvation, mothering, support, or improvement. The same selectivity applied to her friendships and choices of workplace.

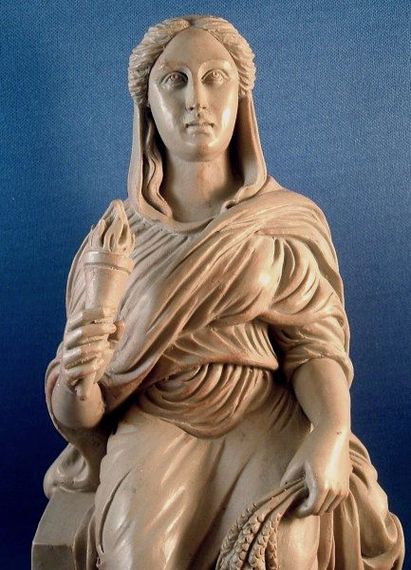

Which is where Demeter comes in...

Every mythological pantheon includes someone like Demeter, the maternal grain and corn goddess who makes everything grow. Across times and cultures she has gone by various names: Ceres, Ninhursag, Isis, Gefion, Rana Niejta, and many others who provide nourishing food, look after the changes of season, and oversee healing mystery traditions that flourish today only in cultures still indigenous.

In the case of all-giving Demeter, she found herself attacked by Hades, who stole away her daughter Persephone, and by Poseidon, who raped her. When King Erysichthon cut down her sacred groves, Nemesis cursed him into an insatiable hunger that drove him to eat everyone in his kingdom, including himself, as Demeter looked on sadly.

Demeter's essential nature is giving, loving, nurturing. Not for nothing is she known far and wide as the Great Mother. But this nature possesses a shadow side that can infantilize whoever ends up held in the Goddess's generous lap. (Compare Isis, who moved earth and gods to bring Osiris back to life, only to lose him permanently to the Underworld.) An unconscious Demeter, which is what codependency amounts to on the human plane, can be controlling, smothering, and self-denying to the point of self-destruction.

Patriarchal cultures set up women for this Shadow Demeter Complex with the ongoing expectation that they be relational nurturers who endlessly give. We might think of the masculine version as the Prince Ivans Complex after the heroic twins of Russian folklore who saved kingdoms and princesses, one after another, until finally being eaten by a sea monster. Whatever their sex or gender, whoever lives from within such a complex is possessed by it. Jung described this dynamic as being overidentified with an archetype.

Of course, "complex" isn't a word you hear much these days outside Jungian and Freudian circles, but it belongs back in public discourse as an alternative to "personality disorder." A complex is a long-standing psychological vulnerability that influences almost every aspect of a person's life, from career to self-image to relationships; a personality disorder denotes a similar vulnerability but unhelpfully implies abnormality, the deviation from a preset standard that takes neither individuality nor circumstances into account. "Complex" is a neutral term: We all have complexes, just as we all have fallabilities and limitations. The real issue is how we meet them. When they have us we're in trouble.

Why would someone want to be a more-than-full-time rescuer / counselor / therapist / mother, even to the point of being unhappy, overstressed, chronically resentful, and physically and emotionally ill?

Because they learned to, usually from very early childhood onward. People who struggle with codependency almost always grow up with an adult family member who demands perpetual emotional care. Often, this is a parent or grandparent who never reached full emotional maturity and who imposes an iron nonverbal "I need you" demand upon other family members, the codependent one in particular. (A family therapy instructor once told us to find out who the family martyr is because they control the entire family.)

When this happens to a child, love and self-esteem get tangled up with unending service. As a result, the codependent grow up starving for love and affection. They feel prized and looked after, safe and significant not for who they are, but for what they do for others. What psychological stability they can obtain depends on making people dependent on them: a fragile basis, and one subject to speedy cancellation.

Sometimes codependency is described as inverted selfishness, with the kindness, empathy, helpfulness, and understanding offered by codependent people "nothing but" a back door attempt to get the specialness and significance every child should enjoy. But in actuality those qualities are quite genuine. The difficulty hides in what unspoken emotional agenda accompanies them.

As a reflection of the inward splitting it engenders, codependency often alternates between long periods of giving -- to the point of weariness and breakdown -- and sudden "me only" moments of rebellion. "Now I'm putting myself first!" the codependent promise themselves over and over, only to lapse back into parenting and rescuing other adults instead of relating to them as equals. They fail to understand that the healthy option is "me AND you" rather than "me OR you."

Typical codependent statements or thoughts hint at this splitting:

"Everything will fall apart unless I work myself to death."

"I don't have time for myself: others need me too much."

"They can't get along without my help."

In an American favorite, "You can't love others until you learn to love yourself," even loving is split into an either-or: others or me. But as a basic capacity love cannot be divided. The ability to love self and others arises as a whole; partitioning it into "self" and "other" undermines it altogether, with the self pole turning selfish and the other pole into infantilizing.

Characteristics of codependency include at least some of the following:

- Feeling responsible for other people's emotional states, often accompanied by hair-trigger sensitivity to those states. "She sneezed and I immediately wondered what I had done wrong."

Obviously this is all pretty miserable for everyone concerned. What to do about it?

Codependency involves a deeply entrenched and highly persistent combination of attitudes, values, repressions, misperceptions, and habits, so it's not going to be "cured" by a workshop or a prescription. Deciding to be more self-loving won't touch it.

At the very least, working honestly with other codependent people and being in therapy should be immediate primary considerations. Relational conflicts require relational healing.

In many unresolved emotional conflicts some past event remains both unmourned and perpetuated by our attempts to undo it. Below the anxiety and restlessness of codependency lurks a powerful unconscious fantasy of obtaining love and appreciation after all by restoring health to the sick, clarity to the confused, availability to the absent, or even life to the deceased. It is painful to finally realize, from the brains down into the bones, that, whatever the current external situation, Dad-within will not stop being selfish and oblivious, or that Mom-within will not suddenly heal and be loving, or that Grandma or Grandpa will not return from the dead with wide-open arms, as they should have much earlier and now never will.

But facing and letting in such an all-gripping sense of loss lowers one into a slow, deep, beneficial mourning -- for the ill who could not be restored, for the early loss of love and support -- that draws misplaced energy out of chronic caretaking and rescuing and gives it back to oneself. Though anguishing, mourning begins a long-delayed healing. The newly practiced capacity for consciously bearing along the ill, the unavailable, the crazy, the addicted, or the dead within one's own psyche, allowing them to be what they actually were instead of trying to save them, also plants fresh seedlings of emotional maturity.

Meanwhile, it's useful to bear in mind that those who struggle with codependency aren't just stuck with a problem to get rid of. More often than not they are highly sensitive and caring individuals who received superb training in service and deep listening.

To pose three questions deeper than cure:

How might that training be turned to more useful and beneficial account?

How might it be directed occasionally toward oneself?

How might it pay homage to the storied figure of Demeter, who not only sorrowed, complained, and was mistreated, but separated chaff from grain, stored up nourishment against drought, washed away her anger in a clear river, and gave everything living its chance to grow, fruit, and thrive?