"Do not train a child to learn by force or harshness; but direct them to it by what amuses their minds, so that you may be better able to discover with accuracy the peculiar bent of the genius of each." - Plato

Plato believed that every child was equipped with extraordinary potential to be successful, and the purpose of education was to help expose that potential. I share in that belief, but I also understand how difficult some students may be.

Troubled youth can be rude and disruptive; their behavior sometimes gets worse as they enter their formative teenage years. When I was in high school, I got into a scuffle with a Latino teen with tattoos all over his arms. Let's call him Luis. Luis emanated a 'tough' demeanor and frequently cursed at our teachers. This student was an outlier for three main reasons:

- My school was predominately white, while he was part of a small Latino minority

- The socio-cultural composition of my school was different (specifically our jargon and wardrobes -- as they tended to be more preppy)

He didn't "fit in" in the traditional sense, so people stayed out of his way. One day -- completely unprovoked -- he called my friend a "fat ass" for eating dessert at lunch. Defending my friend, I called Luis "ignorant," which prompted him to explode with anger. He jumped up and threatened to hit me (and I think he would have), but a bunch of students came to my defense and pulled him away. My school suspended him for a week and shortly thereafter he dropped out of high school. I'm not sure where he went after he dropped out, but I do know that he eventually found himself inside a jail cell.

Just like that.

As I continue to learn about the role school policies play in the mass incarceration of our Black and Latino youth, I begin to question the efficacy of the out-of-school suspension program. What is it and why do we need it? Every student has a life either at home, in a shelter, or on the streets, and that life informs their behavior in the classroom. If a student is surrounded by domestic violence in his home, then his classroom behavior will reflect that. From what I knew of Luis, he came from an unstable home without any viable role models. His father was absent and his mother lived with her boyfriend. Luis's 16-year-old girlfriend was pregnant, yet he was still willing to hit a female classmate. Luis's idea of "masculinity" was misguided and dangerous. If you had asked me then about how my school should handle his misconduct, I would have easily pushed for expulsion.

Now, I am calling for mentorship.

In other words, let's eliminate out-of-school suspensions altogether. By kicking students out of our classrooms, we are sending the message that we have given up on them, that they are troublemakers, and that they are simply not fit for school. Luis certainly received that message and he eventually gave up on school. But imagine how different Luis's life could have been if we had mentored him, if we hadn't shut our door on him? If we had suspended Luis into a mentorship program, we would have committed to a more positive message -- a message that demonstrated care and investment in his future. When my school suspended Luis, they thought they were doing the right thing. Over five years later -- and it's very clear to me now -- I realize they mistakenly suspended his education.

Numbers Don't Lie

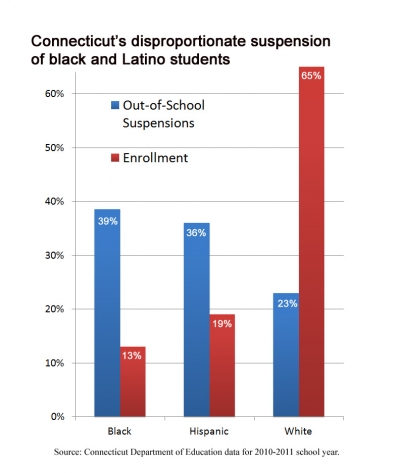

In the 2009-2010 academic year, about 3.3 million students were punished with out-of-school suspensions. Of that bunch, young Black students were about three times more likely to be suspended than white students. Earlier, a report by the Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights found that 28 percent of middle school Black male students were suspended, compared to 10 percent of white males. Eighteen percent of Black females were suspended, compared to only 4 percent of white females. In Connecticut, these figures are a bit more daunting. Take a look at the figure below, which demonstrates the extent to which Black and Latino suspensions severely outnumber their enrollment.

But Numbers Don't Tell Stories

- First, statistics indicate that school administrators issue -- whether intentional or unintentional -- harsher punishments to students of color.

It is by no means a simple ride.

School to Prison

We understand that mass incarceration is a fiscal problem, eating away at state budgets at the expense of much needed investments in public education. But mass incarceration is also a racially charged epidemic. That is, we incarcerate more Black and Latino people than we do any other racial demographic. The frustrating myth is that Black and Latinos are the ones who commit most crimes. Not true. Yet our prisons are disproportionately overflowing with people of color.

Around 40 percent of our nation's inmates do not have a high school degree. A Northeastern University study found that, on any given day, one out of every 10 male high school dropouts are in the criminal justice system. For high school graduates, the number is closer to one in 35. The figure for Black Americans is significantly more discouraging: one out of every four Black male high school dropouts is in jail. This study was dubbed, "The Consequences of Dropping out of High School."

It's important to note that high school dropouts generally have been suspended at least once throughout their time in school. A 2006 study published by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation noted that 32 percent of dropouts quit because they had missed too much classroom instruction and "couldn't catch up". Sixty nine percent of students quit because they weren't motivated to "work hard," although 66 percent claimed they would have "worked harder if more had been demanded of them."

Out-of-school suspensions have long-term consequences for students by signaling sentiments of hopelessness and they impede upon valuable classroom instruction. Students who have been suspended multiple times will likely find themselves dropping out of school. This cycle becomes more devastating as statistics suggest that high school dropouts have a greater likelihood of going to jail. Despite being ruled unconstitutional, the NYPD's Stop and Frisk policy has subjected an unprecedented number of Black and Latino youth to stops by the police. Students of color are simply safer in school than they are in the streets.

New Jim Crow

Bearing a criminal record, no matter the size or severity of the crime, can legally bar people from employment, housing, government assistance, and voting. People might believe that normal life can resume after a jail sentence is over, but nothing can be farther from the truth. When people are released from prison, they are still not free. A former inmate will struggle finding a steady job, signing a lease, and going back to school. He will face a lifetime of challenges trying to regain his autonomy. And, alas, our existing system won't allow him to. This is what Michelle Alexander has coined the "New Jim Crow".

This speaks to the crux of the school-to-prison pipeline: how do we keep our young people of color from going to jail? Well, we stop sending them there.

Suspending to Mentorship

Troubled youth, much like Luis, should stay in school. Their livelihood depends on getting a diploma and we should do everything in our power to help them along the way.

As Dr. Jeff Duncan-Andrade, an associate professor at San Francisco State University and a high school English teacher in East Oakland, California, put it: "We cannot treat our students as "other people's children"-- their pain is our pain." That school of thought encourages us to critically examine zero-tolerance policies: how can we justify abandoning the young people who need our help most?

We can't.

A central tenement to school discipline should include restorative justice policy, which is a more productive alternative to zero-tolerance policies. Restorative justice not only allows for, but also encourages improvement for at-risk youth.

Organizations have been researching the benefits of formal mentoring programs for years, and there is a general consensus in the academic community that mentoring works. Youth with mentors perform better in the classroom and often have fewer excused absences than youth without mentors. The Federal Mentoring Council wrote that "Teachers of students in the BELONG mentoring program in Bryan-College Station, TX reported that mentored students were more engaged in the classroom than students who did not have mentors, and also seemed to place a higher value on school."

The Big Brother Big Sister (BBBS) program is a testament to the efficacy of mentorship. Mentees in the BBBS were "32 percent less likely to report having hit someone over the past year than the young people without mentors."

Mentorship works -- flat and simple. When students engage in behavior that would traditionally lead to suspensions and expulsions, we can (and should) offer them mentorship. We can devise a meaningful mentorship program that will enable them to understand the harm in their behavior, why it was disruptive to the classroom, and how they can fix it. The benefits, however, are two-fold; mentorship can also help us recognize what we are doing wrong, how our students struggle outside the classroom (think: gang violence, dysfunctional families, poverty and hunger), and what we can do to foster a more collaborative and productive environment. Rather than forcing them into three days on the streets, we can issue suspended students three days in a mentorship program right on school property. This is restorative justice.

It is easier said than done, but it is worth considering. There is a generation of young students of color who, if history serves us right, are bound to find themselves embroiled in the criminal justice system eventually. It's our responsibility to, as Plato said, "discover the peculiar bent of the genius in each," and it starts with mentorship.