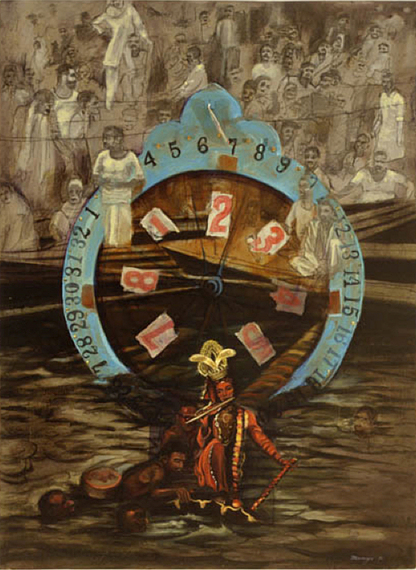

Rob Mango, Krishna Passing the Wheel of Fortune on the River Ganges 1993, oil with mixed media on canvas, 46 X 34 inches

Rob Mango, artist and denizen of Tribeca, NY and former medal winning track star has been running through the streets of New York City since the late '70s when unchecked crime, hopeless buildings and indifferent civil servants characterized the boroughs. New York, with all its energy, potency and power can seem quite surreal at street level on feet that have traversed tens of thousands of running miles coupled with curious eyes that catch every unrelenting detail. Taken the right way, it can become a dreamscape of crossed cultures and mixed metaphors that can either collide or coalesce in a Rob Mango work of art- - and it is here that we see a side of civilization that is raw and resplendent.

To get the most out of the art of Rob Mango I thought it best to pose the following questions regarding the origins and inspirations behind the work.

DDL: I see in one of your exhibition catalogs that you talk about your father, and how he was astonished by the way you responded to the paintings he brought back from his travels to Paris and Rome. It's clear the lasting impact these early exposures to art have had on you, but how much did those particular experiences change the way you viewed the world around you and the life you had already established as a burgeoning athlete?

RM: The European pictures spoke to me in a language that I instinctively understood - a way of speaking back was to reproduce them in oil, Cray-Pas or pastel. At the same time I was spending every Saturday after track meets and Sundays after training runs visiting the Art Institute of Chicago, especially the impressionist galleries. I was copying works by Degas, Monet and Van Gogh and early Picasso. My renditions were not quite replicas, but the fundamentals of impressionism were being devoured by a 14-year-old high school frosh with an insatiable appetite for what a painting is and might be.

Within six months I was analyzing Duchamp, Ernst and the Dadaists -- then the Surrealists. They led me to French literature as I read Andre Breton, followed by Sartre, Nietzsche and Freud.

DDL: In the past, I've talked to you about how you develop paintings as you run -- a unique, mutually beneficial relationship between creative mind and restless body. When one views your work there is also a sense of distant cultural history and architecture that almost conjures up an out-of-body experience. Is there more than just the literal physical traveling that you are experiencing when you are running and observing? How much of your iconography are you visualizing?

RM: While in college I was training at high pain thresholds with some of the best distance runners in the world. My specialty was much shorter, the 880 yard run (800m). Training with these men who specialized in longer distances was my coach's way of making me tough and increasing my endurance. We would train with very hard 6-12 mile runs between a 5:00 and 6:50 minute per mile pace. There would always be a kick or sprint at the end - even practice was a race. I was training with Olympians, national and world record holders: Lee Labadie, Mike Durkin, Craig Virgin and Dave Kaemerer. They were fierce competitors. If I could hang in during the run -- while my fellow runners tried to dump me -- I could outsprint them at the end.

During the middle of these training runs when my mates were ratcheting up the pace, I would fall into oxygen debt - the pain was excruciating. To survive the experience, I would visualize paintings, usually works in progress, but also new pictorial hallucinations as my mind would fill with fragments from my subconscious.

On any given day over the last thirty years I would have a dozen or so drawings, oil sketches canvases and assemblages in progress in my studio. Before heading out the door for a run I would carefully look over each piece of unfinished art - images that would reappear on a screen in my mind during the run. The combination of excess followed by inadequate O2 supply within an hour of running became a powerful period of creation and visualization as many images and solutions to painting challenges would pour into my mind. After the run, rather than my going immediately to work I would make fast thumbnail sketches and notes of what I have visualized.

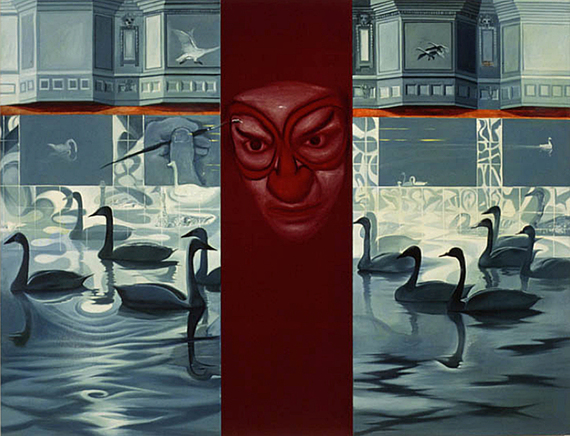

Rob Mango, Self Portrait with Swans 1992-93, oil on canvas and velvet, 65 X 88 inches.

DDL: While you are describing your mental transitions during a grueling run I can't help but think of all of the times I've seen and heard reference to the mirages experienced by hopelessly lost desert denizens. They reach, albeit unwillingly, a similar breaking point that results in a hallucination. Your fitness and ability to preplan and control affords you continual access to your subconscious when you run - sort of the way a trained observer can record all or most of their dreams. I also noticed that you work in series so there must be other stimulus that influences your iconography. It's easy to see what informed a painting such as Burial at Sea (2004), which is directly related to the 911 tragedy, whereas your most current series of mixed media works that celebrate the female form in motion is far more mysterious. What is the influence there? And finally, it is clear the artist's hand, your hand, is a big part of many of your works. You see it very clearly in the narrative of Self Portrait with Swans (1992-3) and Amiss in the Abyss (1989). I am also aware that your narratives are open, they leave a lot for the viewer, any viewer, to expand upon or extrapolate. With that said, is the artist's hand you present the best way for the viewer to enter the work as it implies origin of thought or control?

RM: Fellini reportedly said: "All art is auto-biographical." No argument here. The way I see it, life dictates the rules, not aesthetic philosophy.

My iconography or subjects can be seen in four realms: Art of Ideas 1970-1983. Paintings, drawings and most significantly, 3-D construction and assemblage; The Hero: A Spirit Within, narrative works which featured the artist (myself) as a costumed time traveler; Semi-Nude Male Figures 1994-2000, oil on canvas or paper and many sketches, somewhat darkly rendered that evolved into 3-D sculpted paintings; and Portraits, Women and Couples 2001-2014. In this last category the women are either brilliantly colored, semi-nude or in fashions, often more abstract than realistic. These began as sketches that evolved into small oils, then larger oils and sculpted 3-D paintings. Throughout all of these genres I painted New York City, an ongoing enchantment that may continue until I can no longer hold a brush.

There is also a fifth category that is evolving now and like the other realms, I was forced to move on by disturbing life events. I suppose they can be referred to as stimulus, although that term sounds voluntary. It has not been a gradual evolution for me, rather I was often jarred out of one state of mind and into another by unexpected life events. Pivots, turns, course changes in this artist's tableau were brought about by blows that I would have avoided had I seen them coming. Gradual occurring stylistic evolution gained from quiet detachment was not the basis for the cascade of imagery seen in my new book 100 Hundred Paintings: An Artists life in New York City.

My father often told me I was too sensitive and too intense. He was probably right as I take things quite seriously. Early on, I possessed sensitivity to seemingly everything in the immediate periphery. I dug deep for what was underlying the surface of consciousness. Those around me perceived my painting and creative work habits as obsessive. My creative expectations appeared to others as being more than a mind could endure. All accept my primary subject, muse and inspiration, Helena who accepted my peculiar rugged mentality. She perceived my tolerance for pain and work as who I am and provided encouragement to press on.

To qualify for the title of 'artist' I felt a need to dig deep and reach high with an intensity teachers, friends and family saw as unsustainable. They openly worried about me as I lived on the edge of conventional sanity. It is what made me different, what made me an artist.

While in my early 20s, I created one particular body of work. The aforementioned The Hero: A Spirit Within. It was to be exhibited in a prime New York gallery in 1994. During the exhibition, an abidingly devastating event occurred and a deep torment took hold of me. As much as I attempted to cope and extinguish it, I could not. I was damaged by the actions of my SoHo dealer. Her dismantling of my exhibition in the middle of its announced term smashed my self-belief and hope. My paintings changed from classically executed oils, nuanced with fantasy, history and imagination to brooding, dark, self-portative male figures. (Ironically the gallery then sold the resulting male figures out as fast I painted them, which impelled an even deeper confusion within me). In the end, after being kicked-out of the gallery, I cut up the remaining paintings. A result an entirely new genre of painting emerged from the scraps of sliced-up canvas. From a period of tortured self-destruction evolved the three dimensional paintings that populates much of my book.

On September 11, 2001, I witnessed the planes entering the Twin Towers. At the time I had maintenance contracts on 10 buildings in he attack radius. I was drawn into the recovery, body and soul, for months to come. Tribeca was evacuated but I never left (this is an important chapter in my book). Our neighborhood was dismembered in numerous ways, I did not pick up a pencil for a year. When I finally could feel something again, I was sitting in an outdoor café where I started drawing happy people, primarily women as they are most expressive. The first time in over a year I felt I needed to bring joy to my audience and myself. I looked for female subjects as a vehicle. Those sketches became the paintings you refer to in your question.

I was fortunate to have a mother who nurtured every aspect of my being.

I was equally fortunate to have met a woman of great instinct and savvy in my wife of 30 years, Helena. When my daughter Magdalena came of age, she amplified my devotion to woman as subject yet another notch higher. The women that populate my canvases, the ones you refer to as 'the female form in motion' are above all vehicles for mood. I adapt the color and paint handling style to the frame of mind I capture in each sketch form. I can think of no species on earth that express or offer greater visual and instinctual intrigue than the American woman. So I gave myself to it for a few years, although not exclusively. My love of NYC as subject often intervened.

Rob Mango: A Retrospective will be held at Elga Wimmer PCC located at 526 West 26th Street in New York City from November 6th to the 29th.